Phila. Jewish woman's long ties with John Paul

On Lena Allen-Shore's sideboard, near the photos of her family and the silver menorah she lights at Hanukkah, sit a half-dozen photos of her dear friend Pope John Paul II.

On Lena Allen-Shore's sideboard, near the photos of her family and the silver menorah she lights at Hanukkah, sit a half-dozen photos of her dear friend Pope John Paul II.

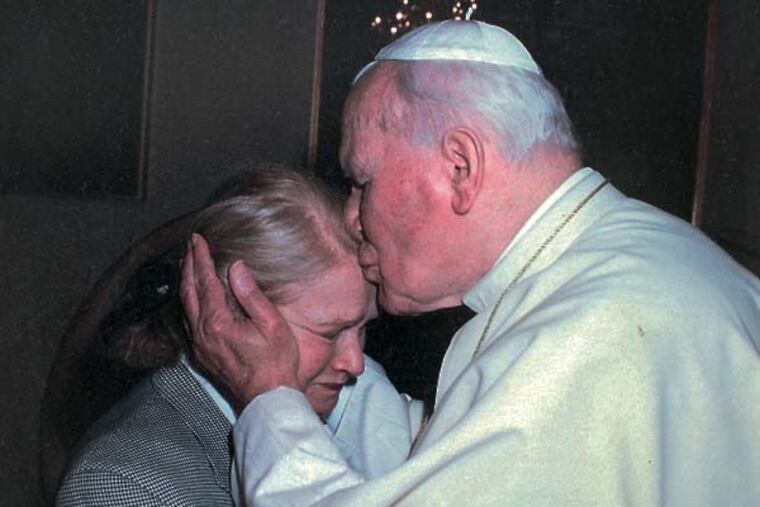

In one he is clasping her cheeks and kissing her head. In another his hand rests on her head in a blessing. And in a third she is presenting him with a book she has written about their separate upbringings in Krakow, Poland, and how they grew so close.

Alas, this Polish-born widow was unable to be in St. Peter's Square on Sunday to see Pope Francis declare the late pontiff to be a saint of the Catholic Church.

"I really wanted to go," Allen-Shore said last week over a lunch of salad and borscht at her apartment in the city's West Park neighborhood. "But the doctors say no. Ten hours on a plane . . ." she shakes her head. "It's too much."

Instead, this petite Holocaust survivor, a retired adjunct professor at Gratz College who has devoted much of her life to promoting ethnic and religious harmony, planned to arise at 4 a.m. to watch her friend honored on live TV.

"He was not only a pope," she said, wiping away a tear. "He was a wonderful human being."

She is small, with blue eyes, high cheekbones, and long henna hair, and she sports gold earrings and rings and a lapis brooch at her throat. The pope, she said, won her enduring admiration for reaching out to Jews and other faiths in ways no other pope had.

She was in Vienna on Oct. 16, 1978, when she heard the astonishing news that Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, the archbishop of Krakow, had been elected pope - the first non-Italian in 455 years.

Days later she wrote to tell him how proud she was, and enclosed two of her books on the Holocaust. "I said that as a Pole during the war he might understand it and do something."

To her surprise, she received a reply. "The Holy Father has read your books," read a short note thanking her. It was signed "Jan Pavel II" by his secretary. She began writing to him about once a year, and receiving replies.

She was by then a friend of Cardinal John Krol of Philadelphia, who reached out to her after a presentation on the Holocaust she made at Villanova University in 1971.

Years after her correspondence with the pope began, Krol had told her "you must meet him" and before the cardinal's 1996 death arranged a private audience.

Their first conversation, at the papal apartment on June 13, 1996, lasted 45 minutes. After reading him a lengthy poem, to which he listened attentively, she burst into tears.

"My mother is crying," her son Jacques, then 40, explained to the pope, "because she has waited 50 years for this moment" of reconciliation.

When she asked "What can we do?" to ensure that Jews are never again called "Christ-killers," John Paul assured her that the Second Vatican Council of 1962-65 had urged Christians not to think that way.

"That is not enough!" she told him. Her frankness evidently pleased him. He nodded, and kissed them both on the head - a marked reversal of the standard kissing of the papal ring.

"He is nothing but goodness," Jacques, an Ottawa lawyer, marveled afterward.

She met the pope again in Rome in 1998. In 2000 he invited her to Jerusalem, where, at the start of ceremonies at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial, he clasped her hands by the eternal flame before a crowd of dignitaries and said something to her, she said, "that I have shared with no one. Not even my family."

Later, he tucked a written prayer into the Western Wall of the temple. "God of our fathers," it read, "you chose Abraham and his descendants to bring your name to the nations. We are deeply saddened by the behavior of those who, in the course of history, have caused these children of yours to suffer."

All differences seemed to disappear in such moments, Allen-Shore observed. "He is saying, 'God is for everyone.' "

In 2002 he invited her to Assisi for a prayer meeting of world religious leaders, and that December sent her an unconsecrated Christmas Eve wafer. The traditional symbol of sharing bread and love, he wrote, "also is a sign of spiritual connection for people of goodwill."

If that were not enough, he hosted a birthday party for her the next year at the papal apartment, where he and her family sang "Happy Birthday" to her in Polish.

All the while she was laboring on her book Building Bridges, a large, affectionate, illustrated account that traces the paths from their Polish childhoods to their friendship. It was published in 2003 by Cathedral Press, an imprint of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

Later editions include a short letter from "Jan Pavel II" thanking her for "seeing deep into my thoughts and understanding the intentions that guided my actions."

The last meeting with her friend came in 2004, after the "concert of reconciliation" at the Vatican that included the chief rabbi and chief imam of Rome. She and the pope had dinner the next day.

Then on April 7, 2005, five days after his death, came her farewell, when Archbishop Stanislaw Dziwisz escorted her and Jacques into the papal apartments, to view his body.

She recited a Hebrew prayer as Jacques said kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead.

"I think that he liked that I was Jewish," she said last week. "That we were joined by our differences."

She laughed when asked what the notion of sainthood means to her as a Jew.

"It's very interesting," she replied. "I don't pray to him. But very often, when I'm praying, I think of him."

856-779-3841 doreillyinq