Quadriplegic Delco priest is on the path to sainthood

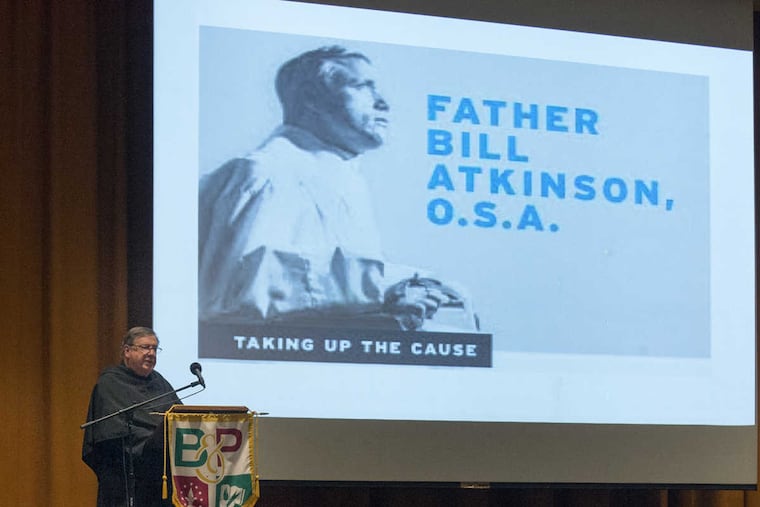

Archbishop Charles Chaput has formally opened the cause for sainthood for the Rev. William Atkinson. With his recommendation, already unanimously approved by the U.S. Catholic Bishops and accepted for review by the Vatican, the long investigation of the priest's life begins.

As the Rev. William Atkinson lay dying at St. Thomas of Villanova Monastery late in the summer of 2006, there was little doubt among the 25 friends and family members who surrounded him. The Augustinian priest, who loved a beer and a good game of pinochle, had lived a saintly 60 years.

A teacher at Monsignor Bonner High School in Drexel Hill for three decades, Atkinson was a quadriplegic, the first in the world to be ordained by the Roman Catholic Church. Those who knew him say he approached his physical challenges with a heroic grace and sense of humor that inspired many.

"He didn't say, 'Why me?' He said, 'Why not me?' and integrated the circumstances of his life into his spirituality," said the Rev. Michael F. Di Gregorio, provincial of the Augustinian Province of St. Thomas of Villanova, of the Order of St. Augustine, Atkinson's religious community.

Last month, Philadelphia Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, leader of the region's 1.5 million Roman Catholics, formally opened Atkinson's cause for sainthood with a Mass at Villanova University, founded by the Augustinians in 1842. With his recommendation, already unanimously approved by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and accepted for review by the Vatican, the long investigation of Atkinson's life begins.

Chaput has appointed two local committees to start the process, to speak with those who knew Atkinson and study letters, books, and other documents written by or about him. Their findings will then be sent to the Vatican, where, if they are approved, the pope will confer on Atkinson the title of Venerable.

For beatification, the next step, a miracle must be attributed to intercession by Atkinson. He would then receive the title of Blessed. A second miracle is required for sainthood.

If the effort is successful, Atkinson will join the two saints who carried out ministries in this region: St. Katharine Drexel, founder of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, and St. John Neumann, a bishop of Philadelphia who started the first diocesan Catholic school system.

"It's long, and a lot of steps, and in God's hands," said the Rev. Frank Horn, a canon lawyer and province treasurer who outlined the process at a community meeting Tuesday at Monsignor Bonner and Archbishop Prendergast Catholic High School in Upper Darby. Atkinson was a 1963 Bonner graduate.

Horn encouraged the audience of 200 to share their experiences with their hometown priest, to pray to him, ask for his intercession, and report successes to the committees building the case for sainthood.

Known as "Father Bill," "Father A," and "Father Ack," he grew up with six siblings in an Upper Darby rowhouse. His father, Allen, drove a train between 69th Street and Norristown; his mother, Mary, a homemaker, volunteered in the kitchen at Bonner.

Blond-haired and blue-eyed with dimples, Atkinson played basketball, football, and baseball at Bonner. His sister, Joan Mullen, of West Chester, recalled that he had a quiet disposition, hated homework, and earned a C average.

Atkinson never said he felt called by God, but at 17, he decided to join the priesthood. "The Augustinian friars taught at Bonner," Mullen said. "I think he just saw something in their way of life, and he wanted to be a teacher."

Atkinson was studying at Good Counsel Novitiate in New Hamburg, N.Y., when he plowed into a tree while tobogganing with friends in February 1965. His spine was severed. He wasn't expected to survive the day. But he did, and remained determined to become a priest.

Surgeons removed a bone from his leg and inserted it in his neck, so he could hold up his head. He struggled through months of rehabilitation. When he enrolled in Villanova to complete his theology studies, he was in a wheelchair.

Friends, family, and fellow seminarians formed a care team to help Atkinson in his daily life. They washed and clothed him, lifted him onto his wheelchair, fed him, wrote notes for him, put him to bed, and remained on call through the night, should he need anything.

"What struck me was his patience," said the Rev. Donald Reilly, a classmate and member of that care team who is now president of St. Augustine Preparatory School in Richland, N.J. "He was an athlete, he was young and bright, and it was such a radical change for him. But he handled it with such grace, style, humor, and joy."

"He changed lives; he changed mine," said the Rev. Robert Hagan, associate athletic director at Villanova. Hagan was a practicing lawyer before he met Atkinson, who inspired him to join the Augustinian priesthood.

In 1973, Atkinson dictated a letter to the Vatican, requesting a special dispensation to become a priest. He needed it because his condition prevented him from performing the sacraments without help. Pope Paul VI granted the request, and Atkinson was ordained in February 1974.

At Bonner, he taught theology, was moderator of the football team, and supervised detention. He wrote poetry and funny shows for the faculty holiday party, and played pranks. He lived at St. Joseph's Friary on campus, where students, colleagues, friends, and family cared for him. He tested the fortitude of new members of his care team by giving them one of the toughest jobs -- emptying his urinal bag.

He spent summers at his family's vacation home in Ocean City, N.J., and regularly sat under the 19th Street Pavilion, where he practiced a kind of Shore ministry. People walking the boardwalk would sit down, to seek advice or play a game of checkers.

"He had this belief that God wanted him to serve by listening and bringing people hope," said Stephen McWilliams, a Villanova film professor who helped care for Atkinson.

Yet doubt and sadness visited him, often in the middle of the night, as he lay on pillows to guard against the bedsores he constantly battled. "At 6 a.m., I would wake up and feel the weight of the cross," he once told Hagan. But "then at 6:01, God would send someone to help me."

In 2004, Atkinson became too ill to continue at Bonner. "It was the saddest day of his life," said cousin Mary Connelly Moody, of Brookhaven. During his time in the monastery's infirmary, Father Atkinson dictated his thoughts into a tape recorder at the encouragement of McWilliams, who later turned the tapes into a book, Green Bananas: The Wisdom of Father Bill Atkinson.

As complications from an infection took him to the edge of life, his brother Al Atkinson, a Super Bowl-winning former linebacker for the New York Jets, and longtime caregiver Richard Heron clipped locks of his hair to preserve as relics, so sure were they of his eventual canonization.

Reilly, then the St. Thomas provincial, said to those gathered in the room that they had witnessed the death of a saint.

"He surrendered his situation to God," Reilly said, "and did it exquisitely well."