Philly courts to stop withholding controversial bail fee

The courts will no longer keep a 30 percent cut of every bail posted. It also abolished its policy on probation detainers, but what will replace it is unclear.

Advocates have been pleading with the Philadelphia court system to end its policy of keeping 30 percent of all posted bail — even when a defendant is acquitted, and even when the bail was posted by a nonprofit community bail fund.

On Wednesday, the court, known officially as the First Judicial District, announced it would do just that.

At the same time, the FJD rescinded its policy on probation detainers — orders that can, either automatically or with a judge's approval, jail people on probation indefinitely if they are charged in a new case or otherwise violate probation.

Some 44,000 Philadelphians are on probation, and 55 percent of the city's jail population is there on detainers.

Last year, Philadelphia's chief defender, Keir Bradford-Grey, wrote to the FJD calling the court's current practice illegal. "The elimination of automatic detainers is not only legally required, but is also good policy," she wrote in the memo, which was made public by WHYY.

But what this new change in detainer policy will mean is unclear.

Previously, automatic detainers were only required when people were charged with very serious violent crimes such as aggravated assault or rape. However, in practice, said Temple University law professor Sara Jacobson, "the reality is they were lodging automatic detainers for most crimes."

"Changing the rule is part of it, but they're going to have to change the default expectations of the judges as well," Jacobson said.

Another lingering question is what the new practice will be for notifying judges when defendants on probation are charged with new crimes.

Jules Epstein, a Temple professor of criminal law, said presumably those judges will still be notified and could still order the defendant to be locked up.

"But at least someone's looking at it," he said. "So will they figure out a way to be smarter about it, or more selective?"

The Defender Association and FJD leadership did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

>>READ MORE: Meek Mill's not alone. Study finds 'indefensible' overuse of probation, parole in Pennsylvania

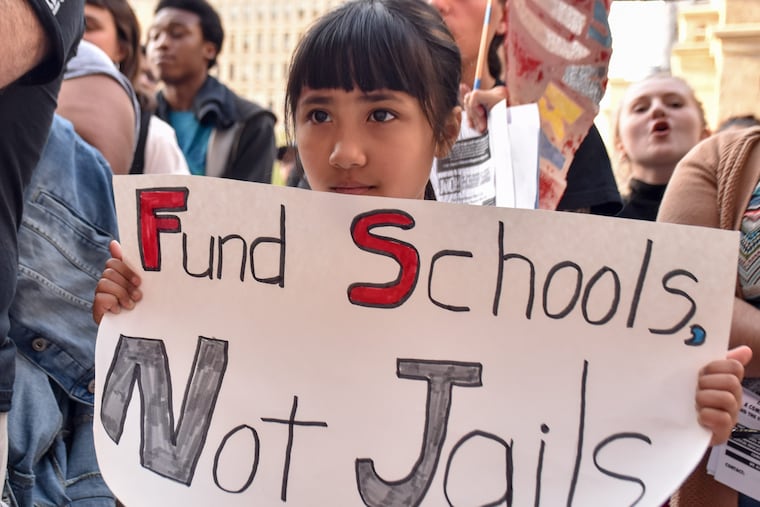

For now, advocates are celebrating the change in the bail process.

"That's an exorbitant amount of money to take from people who are already more than likely poor, who may have scraped up the resources to bail out a loved one and then they don't get the entire portion back," said Reuben Jones, an organizer with the Philadelphia Community Bail Fund.

He said the bail fund has posted more than $120,000 in bail, and lost at least $35,000 in fees collected to the courts. That hurts, given that its work is crowdfunded, $15 or $20 at a time. The fund is currently not posting bail as its reserves are low, and it's saving up in advance of a planned holiday-season bailout.

Councilman Kenyatta Johnson said the issue came to his attention at a community forum in February, and negotiations have been inching forward since then.

"A lot of the attendees and advocates expressed their outrage with how the criminal-justice system collects money and balances its budget on the backs of primarily poor people," he said.

Altogether, the city set aside $2.9 million in its fiscal 2019 budget to allow for the end of this fee, said Julie Wertheimer, director of criminal justice in the Philadelphia Managing Director's Office. That was accomplished through advocacy from City Council and support from the mayor.

Mayor Kenney, in a statement, praised the FJD's announcement: "Enacting this reform is in line with our joint efforts to safely reduce the jail population by 50 percent by the year 2020, and — most importantly — to reduce racial-, ethnic- and economic-based disparities in Philadelphia's criminal justice system."