Gloucester Township says pay-to-play proposal would end transparency

For months, activists in Gloucester Township have campaigned for an ordinance that they say would prevent firms that make political contributions from getting contracts with the town.

For months, activists in Gloucester Township have campaigned for an ordinance that they say would prevent firms that make political contributions from getting contracts with the town.

Similar measures have passed in other New Jersey municipalities, but Gloucester Township officials have resisted. Such a ban, they say, would funnel campaign contributions through special-interest nonprofit groups that, unlike traditional campaign committees, don't have to disclose where their donations come from.

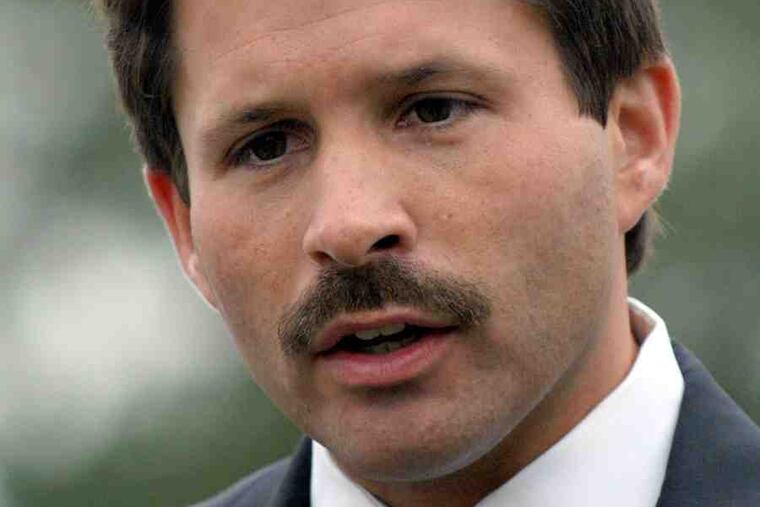

"Right now, you know exactly who is giving money," said Mayor David Mayer. "Transparency is first and foremost. I don't think" advocates of the ordinance have "thoroughly thought through the public-policy obligations."

So-called pay-to-play laws, designed to prevent donors from unfairly profiting from relationships with politicians and parties they backed, remain a tough sell to many New Jersey elected officials. Five years after the Legislature authorized municipal governments to create rules prohibiting pay-to-play, only about 110 of the state's 587 municipalities and counties have done so.

Of those, about 80 - including Cherry Hill and Collingswood - have what are considered strong laws, said Heather Taylor, spokeswoman for the Citizen's Campaign, an advocacy group that is pushing for stricter pay-to-play laws statewide. Those measures close loopholes that might allow a contractor to donate to a county party fund, then work in a town where that money could find its way into a candidate's campaign war chest, she said.

"We've done studies in certain towns, and it's the government contractors who largely finance local campaigns," Taylor said.

In Democratic-controlled Gloucester Township, the donor rolls of local political action committees (PACs) are filled with town employees and law firms.

Leading the effort to enact pay-to-play measures in Gloucester Township is the advocacy group South Jersey Citizens. Joshua Berry, its political director, estimates that of the more than $168,000 raised by Democratic PACs in Gloucester Township last year, about $120,000 came from individuals or entities that had contracts with or were employed by the township.

"Pay-to-play has infected our town. It is the core of the political machine. If you stop pay-to-play, you've choked their machine," Berry said.

Mayer, a Democrat and former assemblyman, said the group's campaign is politically motivated.

"I hope when they're collecting signatures, they explain they have endorsed a Republican candidate," the mayor said of South Jersey Citizens.

The group says that it is not aligned with any party, though Berry is a registered Republican.

Special-interest nonprofits, which to date have mostly been involved in federal races, could potentially become involved at the local level, said Joe Donohue, deputy director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

"It's not the case now," Donohue said. "The way stuff tends to happen, it starts at the federal level and works its way down. It depends on the size of the municipality. It depends on the success of these groups."

While many in political circles are skeptical of how effective pay-to-play ordinances are, the measures appear to have had some impact.

Political donations by public contractors have decreased steadily since 2007, when they totaled $16.4 million statewide, according to the commission. Last year, donations were $9.4 million, the group said.

But an April report by the commission noted that the recession had reined in public projects, giving firms less incentive to curry favor with politicians. Contractors also have found ways to donate that may get around the state's campaign-finance laws, the report found.

Removing insider deals from government is nearly impossible, said John Weingart, associate director of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University. And an insider deal is sometimes in the eye of the beholder.

"You find what you're looking for. You can always find local attorneys or engineers who have friendships with elected officials," Weingart said.