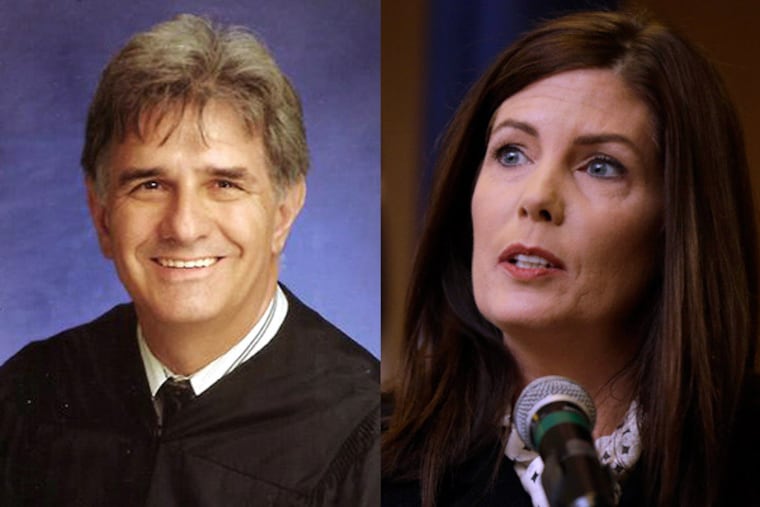

Sources: Kane's office obtained judge's private emails

Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen G. Kane's office gained access to the private emails of a state judge - without his permission or knowledge - and offered to provide them to the news media, The Inquirer has learned.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen G. Kane's office gained access to the private emails of a state judge - without his permission or knowledge - and offered to provide them to the news media, The Inquirer has learned.

Kane's representatives obtained copies of Judge Barry Feudale's 2013 email exchanges with Inquirer reporters and his personal lawyers after she successfully pushed for his removal as the judge in charge of a key investigative grand jury, according to three people familiar with the matter.

It was unclear how the emails were obtained.

Kane's spokesman, Chuck Ardo, said, "I know of no involvement of anyone from the Attorney General's Office in obtaining or distributing" Feudale's emails.

Ardo did say that news organizations had recently contacted Kane's office, saying they had copies of the judge's emails. But he insisted that neither Kane nor anyone in her office had any role in providing them to reporters, or acquiring them in the first place.

At the same time, he said, Kane's office "may have provided" some of Feudale's emails to judicial regulators and disciplinary agencies.

Ardo said he assumed any emails the office obtained were retrieved from its computer servers.

"If the emails were not somehow possessed on our servers, it boggles my imagination to figure out how [they] may have been obtained," he said.

The messages between Feudale and the Inquirer reporters were not sent to addresses routed through servers in the Attorney General's Office. This makes them different from the email messages of others - some containing pornography - that Kane has made public to decry the exchange of offensive material on state time.

Rather, the Feudale emails were messages exchanged among the private accounts of the judge, Inquirer reporters Angela Couloumbis and Craig R. McCoy, and two lawyers representing Feudale, William Costopoulous and Samuel C. Stretton.

In the emails from 2013, the Inquirer reporters questioned Feudale about his removal from his post overseeing the grand jury. Five people with knowledge of the emails said Kane and her representatives had suggested that the messages raised questions about Feudale's conduct as a judge in his readiness to discuss Kane with the reporters and others.

A source with copies of the emails showed three to an Inquirer reporter, and they matched the originals.

Other sources said Kane's office had had copies of the emails since at least 2014.

Two people familiar with the matter said the emails were being distributed in recent days by Ken Smukler, a political consultant for Kane.

Smukler said Tuesday he had obtained emails of the Inquirer reporters from "individuals outside the Attorney General's Office." He declined to elaborate.

"What I have chosen to do or not to do with that information is none of [The Inquirer's] business," he said.

Smukler, a veteran campaign adviser, has provided communications advice to Kane's office, according to Ardo. He helped develop Kane's response to a move by the state Senate last week to consider removing her from office.

Sources said copies of the emails had been delivered to WHYY and also sent to the Legal Intelligencer, which covers the Philadelphia legal community.

Feudale said last week that he never granted Kane - or anyone from her office - permission to access his messages.

"I am outraged by the invasion of my privacy. It shouldn't happen to anybody," Feudale said. "It not only upsets me, it saddens me."

Feudale said he used his personal computers to exchange the emails with the reporters and his lawyers. He also noted that he was not in a government job at the time the messages were sent, and said he had no access to state-issued computers.

Feudale said that he had checked with his Internet service provider, PennTeleData of Palmerton, Pa., and that the firm told him the Attorney General's Office had not accessed his account with a search warrant or wiretap order. The firm declined to comment, saying it would not disclose information about a customer.

Michael Risch, a law professor at Villanova University who specializes in Internet law, said it would have been legal for one of the emails' recipients to provide the messages to someone in Kane's office.

Beyond that, he said, there were few lawful methods by which Feudale's emails could have been obtained without his permission.

The federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, he said, makes clear that "accessing a computer without authorization in order to get information is a crime."

In a widely publicized 2008 case, the TV news anchor Larry Mendte pleaded guilty to illegally accessing a colleague's computer after the FBI discovered he had secretly obtained passwords for three email accounts of a fellow journalist, then leaked information about her to reporters.

Awaiting trial

Kane, a Democrat who is the state's top law enforcement official, is awaiting trial on criminal charges. Prosecutors say she illegally leaked confidential documents to a newspaper to plant a story to embarrass a critic, then lied about it under oath.

They say her target was Frank Fina, for many years the top corruption prosecutor in the Attorney General's Office.

Kane, 49, has pleaded not guilty to perjury, conspiracy, obstruction, and other crimes.

Authorities also charged Patrick Reese, the head of Kane's security detail, with illegally accessing the work emails of staffers in her office in an effort to learn about the criminal investigation of her.

Reese did this, prosecutors said, by looking for email messages stored in the office computer servers in Harrisburg. According to the affidavit of probable cause in Kane's criminal case, Reese sought to obtain emails between the attorney general's staff and Couloumbis and McCoy, among others.

Emails with reporters

In July 2013, the two Inquirer reporters exchanged about 15 emails with Feudale as they gathered information for an article about his ouster as presiding judge of one of the state's three investigative grand juries.

The reporters learned of Feudale's removal after the fact. He had been secretly removed at Kane's request in sealed filings with the state Supreme Court.

Kane complained that Feudale had demeaned her predecessor, Linda Kelly, and disparaged Kane's review of how Fina conducted the investigation of Jerry Sandusky, the serial child molester.

In her most serious accusation, Kane said Feudale had intimidated one of her secretaries by displaying a large knife.

In interviews and the email exchanges, Feudale gave his side of the dispute.

He agreed that he had erred in poking fun at Kelly, and provided the reporters with a copy of an email to Fina in which he had made a joke about her. But he stood by his criticism of Kane's review of the Sandusky case and vigorously disputed her allegation that he had brandished a knife.

In the exchanges with reporters, Feudale shared some material generated during his dispute with Kane. But he also rebuffed the reporters on other matters, saying he could not talk about certain issues because he was bound by grand jury secrecy.

"Nice try, guys, but sorry," he wrote at one point, in declining to answer questions. "I am not willing to violate the law and my commitment to secrecy, even as a former grand jury judge."

In the emails, Feudale was critical of Kane's agenda.

"It is about the furtherance of her political career," the judge wrote to the reporters at 3:15 p.m. July 14, 2013.

In other messages, he praised Fina, something the judge's detractors say betrays a bias.

"Fina is the real deal," Feudale wrote in a July 3, 2013, email. "Brilliant mind, photographic memory, fierce but ethical advocate."

At various points, he sent copies of the emails to his lawyers, Stretton and Costopoulous.

In an interview last week, Stretton said there had been an "inexcusable" violation of the judge's privacy rights.

Stretton said he saw the sharing of Feudale's emails as an intrusion on the secrecy of the attorney-client relationship, even if he and the judge were in contact with third parties, such as the reporters.

"But more importantly, she should not be going into private emails," he said.

Several sources say word of the emails has been circulating among prominent defendants convicted in cases led by Fina in which evidence was put before grand juries presided over by Feudale.

They see the exchanges as possibly helpful to appeals. One described them as documenting "a conspiracy between Fina and Feudale" to leak information to The Inquirer.

In recent weeks, Kane has publicly said she was concerned that before she took office, there may have been leaks from grand jury investigations presided over by Feudale and led by Fina.

She signaled her concern last month when a lawyer pursuing Sandusky's post-conviction appeal filed a motion asking to see any emails between Feudale and Fina.

In response, Ardo said Kane "has strong suspicions that the leaks came from people associated with this office" under her predecessors.

A week ago, according a person familiar with her decision, Kane appointed two agents to pore over emails and other exchanges between judges and state prosecutors, including Feudale and Fina.

In his role supervising the grand jury, Feudale, a Democrat, was the referee on legal issues in a succession of high-stakes investigations, including the so-called Bonusgate and Computergate corruption cases, the Sandusky case, and the investigation of Pennsylvania State University administrators who allegedly covered up his crimes.

Feudale was an activist judge, even issuing his own statement affirming one key grand jury report, saying jurors were rightly "mad as hell" at entrenched corruption in Harrisburg.

Within weeks of taking office, Kane was at odds with Feudale. Four months into her term, she asked the Supreme Court to remove him.

The grand jury over which Feudale presided was created and staffed by the Attorney General's Office. Its hearing room - and Feudale's adjacent chambers - was on a lower floor in the same Harrisburg building as Kane's office.

In the spring of 2013, Feudale said in a recent interview, he returned from an out-of-state trip to discover that three key files were missing from his desk.

He called Capitol Police to report a break-in, records show. "Barry Feudale reported 3 files were taken from his office," the police report said.

A short time later, Feudale said, the assigned officers called him to say, "Judge, we were told to discontinue the investigation."

Troy Thompson, spokesman for the Capitol Police, said the case was turned over to the Attorney General's Office. Feudale said he never heard from anyone in that office about the break-in.

The judge acknowledged that he was not very security-conscious about access to his office or his email.

For one thing, he said, he left the key to his chambers in the base of the holder for the American flag in the main grand jury room.

As for his email password, Feudale said, he had trouble remembering it, so he gave it to the two secretaries of the grand jury - both of whom are employees of the Attorney General's Office.

He also said he wrote the password on a note that he stuck to a pullout shelf on his desk.

Feudale was officially removed from his grand jury post in May 2013. Under court rules, Feudale, 69, remains a Common Pleas Court judge until he turns 80.

Shortly after his removal, Feudale returned to his chambers one last time. The judge arrived on the eighth floor of the Strawberry Square office building - eight floors below Kane's offices - to retrieve personal papers.

He was met there by two of Kane's top aides and the office's computer expert. It was a tense gathering.

At the session, sources said, Feudale requested that private material on his computer be kept private. An office computer expert was called in to help separate Feudale's private items from public material.

Also there was Cambria County Court Judge Norman A. Krumenacker III, newly assigned to take Feudale's place as grand jury judge.

Afterward, Krumenacker wrote to Kane, asking her to give Feudale a copy of his hard drive so he could retrieve personal information on it.

"I request that you confirm either in writing or by email that this has been accomplished," he wrote.

According to Feudale, Kane never provided him with such a copy.

Without further access to his office or state-issued computer, Feudale said, he used his personal desktop computer, as well as a laptop unit his son gave him, to write the emails now being circulated among others.

610-313-8212@cs_palmer

Inquirer staff writer Chris Hepp contributed to this article.

Key Investigative Grand Jury Cases

StartText

Presiding judge: Barry Feudale

Leading state prosecutor: Frank Fina

Bonusgate: Ten convictions of state House Democrats.

Computergate: Nine convictions of State House Republicans, including former Speaker John Perzel (right).

Jerry Sandusky: Conviction of former Penn State assistant football coach for molesting 10 boys.

Penn State administrators: Three administrators, including former president Graham B. Spanier, await trial on charges of covering up Sandusky's wrongdoing.

State Rep. Bill DeWeese: Former speaker and Democratic leader convicted on corruption charges.

EndText