Senate GOP plan would delay corporate tax cut, protect mortgage interest deduction

GOP Senate leaders unveiled a tax package that would delay cutting the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent until 2019. That's a major departure from Trump's insistence on immediate tax cuts that he says are necessary to spur the economy.

WASHINGTON – Senate Republicans are forging their own path on the effort to overhaul the U.S. tax code, offering a plan Thursday that would delay an immediate corporate tax cut President Trump has demanded and blow up House Republicans' carefully crafted compromise on a controversial tax deduction.

GOP Senate leaders unveiled a tax package that would delay cutting the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent until 2019. That's a major departure from Trump's insistence on immediate tax cuts that he says are necessary to spur the economy.

The one-year delay would lower the cost of the Senate bill by more than $100 billion, giving negotiators more revenue for other changes. But it could also delay companies moving back to the United States from overseas or prompt them to hold off on other decisions as they wait for the corporate rate to fall.

The unveiling of the Senate plan, combined with a House committee vote to send a version of its bill to the House floor, is a step forward in the party's race to rewrite the U.S. tax code before year's end. Before those bills could become law, however, the House and Senate must pass matching versions of the legislation. And as leaders in each chamber grapple with difficult trade-offs on tax rates, deductions and deficits, the House is making decisions the Senate won't accept, and the Senate is doing the same to the House.

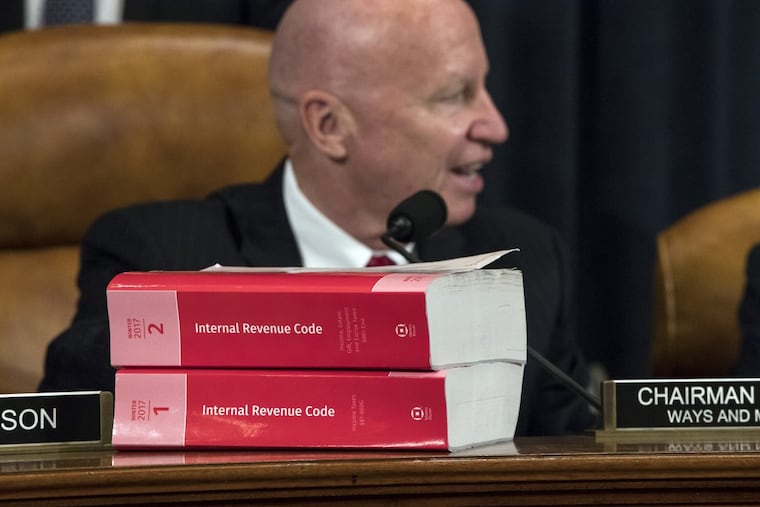

"We know we have more work yet to be done, but this is a historic step," House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady (R., Texas) said. "Will there be some differences? Of course, that's the legislative process. We welcome that."

Those differences became more pronounced Thursday, making the path forward more complicated. Republicans face intense pressure to pass a tax bill or face ending a year of near-complete control over the federal government without a single major legislative achievement to bring voters and donors.

Trump and his party face finishing a year in which they enjoyed near-complete control of Congress without a single major legislative achievement, leaving them with little to show donors and voters during 2018 campaigns after promising a broad, conservative restructuring of American government.

Delaying the corporate-tax-rate reduction was one of many tough choices Senate leaders made as they tried to craft a bill that would lower taxes but also add no more than $1.5 trillion to the debt over 10 years. Further changes are expected next week as lawmakers begin debating the measure.

The bill does not comply with Senate rules that prohibit certain legislation from adding to the deficit after 10 years. This could force Republicans to make some of the tax cuts temporary, though those decisions have not yet been made.

Senate Republicans briefed White House officials on the one-year delay, and Trump administration officials said they would accept such a provision. To try to prod companies into expansion next year, the Senate bill would allow companies to immediately deduct all capital investments in 2018. Companies would be allowed to immediately expense these investments for five years.

In a move that could cause major tension in the House, the Senate bill also would prohibit Americans from deducting certain state and local taxes from their federal bills, a change that could raise taxes overall for Americans in high-tax states such as New York, New Jersey, California, Oregon and Illinois.

The Senate's approach to state and local taxes is at odds with that of the House, where Republicans settled on a compromise – scrapping some of the state and local deductions but still allowing a deduction of up to $10,000 on property taxes – after GOP lawmakers from high-tax states revolted against an initial House plan to scrap the deduction entirely.

The proposal to eliminate that deduction in the Senate and House bills would apply only to individuals and families, while businesses would still be allowed to claim the deduction. The discrepancy could further inflame Democrats, who have criticized the GOP tax cut effort as offering too many benefits for companies and stripping benefits away from individuals and families.

"Senate Republicans are doubling down on their gamble with middle-class family budgets to pay for massive handouts to big corporations and tax cheats," said Sen. Ron Wyden (D., Ore.).

Trump, traveling in Asia this week, called in to a meeting between White House officials and a collection of moderate Senate Democrats on Tuesday, hoping he could win their support for his tax effort. The call was part of a broader push from the president to enact a major piece of his domestic agenda, with repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act having failed and the infrastructure package he campaigned still in its nascent stages.

The stakes are also high for Republicans in Congress, where Republicans on Tuesday night watched their party peers in state and local races get ousted in a string of election defeats. Top GOP officials were split on whether the losses would complicate the tax overhaul. Rep. Mark Meadows (R., N.C.), chairman of the conservative House Freedom Caucus, said Wednesday that it demonstrated the need for the GOP to deliver on its promises.

"We need to start making our legislation match our campaign rhetoric," Meadows said.

Businesses are watching the process closely as well. The stock market fell Thursday after reports the Senate bill included the one-year delay to corporate tax cuts, with investors worried that it could force companies to hold back expansion plans.

The Senate bill also eliminates the personal exemption many Americans take to lower their taxable income, but it does expand the tax credits for families with children and nearly doubles the "standard deduction" taken by tens of millions of taxpayers who don't itemize their returns.

The Senate plan would also keep the mortgage interest deduction intact, according to a Republican official who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the official was not authorized to speak publicly. In the House bill, homeowners would be allowed to deduct only interest payments on their first $500,000 worth of home loans, a proposal that generated fierce opposition from the housing industry, while the Senate bill would keep the current threshold of $1 million.

Another feature of the Senate bill would be to make changes to the estate tax, a levy placed only on very large estates when they're inherited from their deceased owner. The House bill would eliminate the estate tax by 2024, while the Senate bill would instead reduce the number of people who have to pay it by doubling the size of estates that are exempt from being taxed.

It would also continue allowing people to deduct payments on student loan interest and to deduct some medical expenses – a provision dropped from the House plan that could lead to significantly higher taxes for many households, particularly for the elderly.

The Senate bill would lower tax rates across income levels as a way to lower tax bills for most Americans, Senate Finance Committee aides said.

The package as currently constructed, however, has significant problems.

Senate Finance Committee aides said they planned to make adjustments to the legislation because it probably does not comply with the rules for a special Senate procedure they hope to use to pass the bill with 50 votes, rather than the 60 votes typically needed to beat a filibuster.

Republicans control 52 votes in the 100-seat Senate, meaning they can only lose two members if they want to pass a bill without Democratic support. A 50-50 tie would go to Republicans, as Vice President Mike Pence would cast the tiebreaking vote.

It's because of that delicate majority that many White House officials expect a tax bill – if it eventually becomes law – to more closely resemble the Senate bill. Senate Republicans will work to resolve differences among themselves in the next few weeks, but major changes made in the House could upend any agreement.

Senate lawmakers also must grapple with strict rules that regulate how a tax-cut bill is designed. To use special Senate procedures to get around a filibuster from Democrats, Republicans must write a bill that does not add more than $1.5 trillion to the debt over 10 years.

Republicans such as Sens. Bob Corker (Tenn.), Jeff Flake (Ariz.), and James Lankford (Okla.) have said they would not support a tax plan that adds too much to the debt, creating a bloc of votes that would be able to kill the bill if they aren't appeased.

House Republican leaders are facing difficult decisions as they try to advance their tax bill. On Thursday, House Ways and Means Committee Republicans voted to advance their bill out of committee. The vote, which clears the bill to advance to the House floor, included revisions meant to eliminate a $74 billion shortfall and address other issues complicating the bill's passage.

To offset the various revenue-losing provisions introduced Thursday, House tax writers opted to increase tax rates on foreign assets that multinational corporations move back to the United States.

The House revisions would also direct further benefits to middle-class taxpayers. It would restore the Child Adoption Tax Credit left out of the previous version and allow for a deduction of moving expenses available to active-duty military members. The Child Adoption Tax Credit is also included in the Senate bill.

Other changes in the House bill are directed at businesses, including a further rate reduction for certain qualified "pass-through" firms that send their earnings to their owners to be taxed as individual income.

Earlier versions of the bill established a new 25 percent rate for income from "pass-through" firms that send their earnings to their owners to be taxed as individual income. But business owners already paying a top individual rate of 25 percent or lower would not benefit. The revised bill creates a rate as low as 9 percent for some small-business income.

The change was enough to win support for the House bill from a key holdout, the National Federation of Independent Business. "This amendment would create substantial tax relief for millions of small-business owners who were left out of the original bill," the group said.

There are other notable differences between the Senate and House bills.

In a break from the House plan, which kept the top marginal income tax rate at the current 39.6 percent, the Senate bill would slightly lower it to 38.5 percent – a win for advocates of supply-side economic theory who argue that a lower top rate will grow the economy.

The House bill would immediately cut the corporate tax rate to 20 percent, offer families a five-year "flexibility credit" of $300 per parent, and expand the child tax credit. It would also collapse the seven income-tax brackets paid by families and individuals down to four, only taxing income above $1 million at the highest rate of 39.6 percent.