Williams striking many notes beyond charters

State Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams' campaign at times can feel a bit like a play in rehearsal, the protagonist still groping his way to the emotional heart of his role.

State Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams' campaign at times can feel a bit like a play in rehearsal, the protagonist still groping his way to the emotional heart of his role.

So it seemed Saturday as the Democratic mayoral candidate dashed across the city on a bitterly cold but brilliantly lit day.

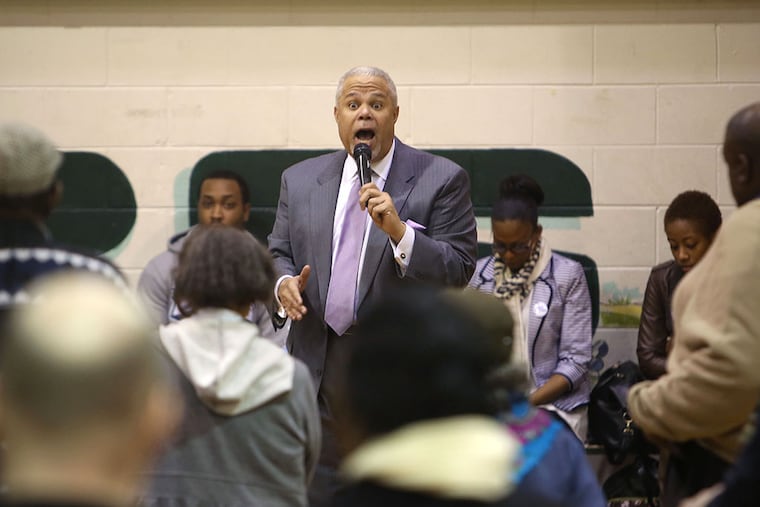

During stops at a union hall in South Philadelphia, an election forum in West Oak Lane, and a community meeting in Germantown, Williams unspooled his message, smoothly at times, awkwardly at others, and tweaking lines along the way to fit his audience.

Accepting an endorsement of the Sheet Metal Workers, Williams told an auditorium filled with work-worn men and women that he had absorbed the lesson of hard labor from his grandfathers, both postal workers.

Later, for largely African American residents in Germantown, his grandparents' commitment to civil rights found voice.

Along the way, Williams sold his vision for schools, policing, and small business before offering a promise.

"There should be a hand reaching out to help you," he said in one iteration. "That does not happen from a lofty office on the second floor of City Hall. It happens because your mayor comes to you, even after the election."

Williams is hoping to parlay experience earned over 26 years in the state legislature, 16 of them in the Senate, as a ticket to the mayor's office.

He comes to the race as the perceived front-runner, largely because he is an accomplished African American candidate running in a city with a plurality of African American voters.

Just as another candidate - James F. Kenney - has dismissed such "racial math" as outdated, so does Williams.

"I agree, voters are smarter than that," he said. "And it works both ways. I don't expect only African Americans to support me."

Rather, he has pitched himself a candidate for "one Philadelphia," and has promised to heal divisions across geographic and demographic lines.

The task before him is ending a perception - a wrong one, he argues - that he is a one-issue candidate: pro-charter schools.

"Charter schools alone are not going to fix education in Philadelphia," he said. "I never say that. I never have said that. I have always been a supporter of public education."

Rather, he is an advocate of schools that work, he said, be they charter, magnet, or neighborhood.

The focus on schools, while important, can overshadow the range of issues he has taken up, Williams said.

He understands, however, how it might have come to this. Five years ago, in a failed bid for governor, he benefited from $5 million in support from three Bala Cynwyd financial traders, who favor, as he does, giving students options beyond failing public schools. The enormous contribution cemented Williams' reputation more narrowly as a charter-school advocate.

The trio is planning to spend perhaps as much in support of Williams' mayoral ambitions, but through an independent organization that, under city election rules, legally can have no connection with Williams' campaign. Which means Williams is not permitted to say how the group spends its money or portrays him and his opponents in election ads.

"I think, as a citizen and candidate, any time you don't have control over how you are represented, you are not going to feel comfortable," Williams said. "But what am I going to say to you? That I don't want the support? Of course I do. . . . Will I get attacked for it? Yes, I will."

A solution is to raise campaign funds to conduct his own ad campaign.

"I spend an average of five hours a day on the phone asking people to support my campaign," he said. "Driving to Harrisburg, you are on the phone, asking people for support. You do your job and get back on the phone."

His days are long, beginning at 5:30 a.m. with a trip to the gym, meandering, with evening campaign stops, as late as 11 p.m.

"You really don't notice it while you are doing it," he said. "I guess I am living on adrenaline right now."

Saturday was relatively short, just 10 hours. His visit to the Sheet Metal Workers Hall started at 9:45 a.m. He ended the day at 7:30 p.m. with a fish fry in West Philadelphia. There were four stops in between and multiple cakes for a candidate celebrating his 58th birthday.

("I'm having none of that," Williams told the crowd at the Germantown Life Enrichment Center when presented the second cake of the day. "Everybody is going to have to take a big grandma piece home.")

Whenever he was given a chance to speak, Williams offered some version of his stump speech.

Key elements, beyond schools, include reducing wage and business taxes while increasing commercial real estate taxes; putting cameras on police officers to monitor their actions and cameras in high-crime areas to improve police safety; and providing targeted tax incentives to lure large employers to city neighborhoods.

And then there are the Eagles.

In his quest to find common ground across the city, Williams evokes the emotional ride the NFL team has provided its perennially disappointed fans.

Saturday, he made a most unlikely pledge.

"In four years, we are going to the Super Bowl," he told the crowd in Germantown. "I will personally go down to the stadium and take the mike from Chip Kelly and smack him on the back of the head and say we want this."

If the cheers that followed are any measure, he's a stone-cold winner.

215-854-2594