Even in death, families say, black men face bias

When it comes to asking for victim compensation payments, the relatives say, accusations of criminal conduct are raised.

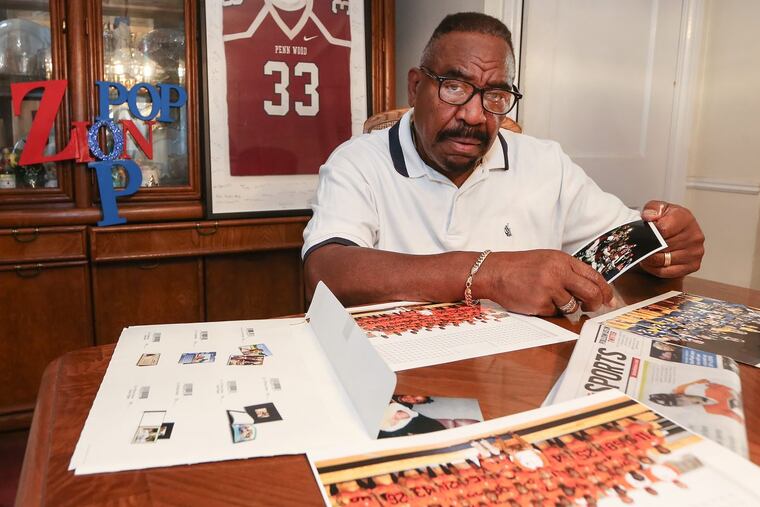

It is closing in on a year since Thomas Vaughan, 73, watched his grandson Zion step out the front door of his Yeadon home for the last time. Zion, a popular Penn Wood High School senior and a linebacker on the school's football team, was killed less than a block from his home by a single gunshot to his back.

At the time, police told reporters there was no apparent motive. They still have not arrested a suspect.

Yet when Vaughan applied to the state Victims Compensation Assistance Program for the $6,500 in funeral expenses available for homicide victims, the application was rejected. The reason: His grandson, who had no criminal record, had been involved in an illegal activity that caused his murder.

"They said Zion was a drug dealer and that this was a drug deal went bad. I have never seen Zion do drugs, much less sell drugs," Vaughan said. On the contrary, he said that Zion, who hoped to attend West Chester University, had become deeply involved with the church and was scheduled to be baptized two days before his funeral. "Why do black kids get the rap of drug dealer?"

Yeadon police declined to comment on Vaughan's case. At a hearing last week to appeal the determination, a Yeadon detective noted he had found five dime bags of marijuana at the crime scene and said Zion had been in communication with Philadelphia gang members. To Vaughan, that wasn't convincing. "He doesn't even have a suspect, yet he's going to incriminate my grandson?" The court has yet to decide the case.

If Zion were still alive, police would have to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to convict him. As it is, they need to prove it only by a preponderance of evidence — that is, that it's more likely than not he was involved in crime.

And unlike in a criminal case, the lawyer representing Vaughan, Angus Love of the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project, was not provided with the evidence against Zion in advance of the hearing. Love said he's begun taking on these cases after hearing concerns from a victim advocate who believed there was a pattern.

"She was very disturbed that African Americans were applying for compensation for their dead relatives and being told they were drug dealers," he said.

Pennsylvania's victim-assistance fund, run by the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency, takes in about $12 million a year from $35 fees imposed on people convicted of crimes. In 2016, it received 6,373 claims from crime victims, paying out an average of $2,800 apiece. It denied 401 claims — 154 of those for illegal activity.

A PCCD representative said the agency does not comment on individual cases. Though applicants are asked to provide their race for statistical purposes, Jeffrey Blystone, coordinator of the program, said he had no way of tabulating how many of the claims were submitted by minorities.

Chantay Love, of EMIR Healing Center, a victim assistance group, said that out of the families of a few hundred murder victims the organization assisted last year, 27 were denied assistance. Some had sought funeral funds; others, whose family members had been killed in or near their homes, had hoped for money so they could relocate to someplace they felt safer.

Some appealed, a few of them successfully. (Only about one case a month statewide is appealed all the way to a hearing before an administrative court judge.) She said many other families just want to move on.

"So far the ones that were overturned at appeal were the white ones. It wasn't the black ones," she said. "The racial bias happens because many African Americans who are murdered may have had a criminal background — even if they have turned their life around. When something happens to them, it doesn't mean it's because of their background."

To her, the state victim-compensation law makes these decisions too subjective. People suffering from addiction, for example, are sometimes painted as dealers instead. For families who are already often living in poverty, that's difficult to disprove.

"The persons who are impacted are the ones who are putting the pieces together, not the ones who are deceased," she said.

She said some families take on debt to pay for the funeral. At least one, without the funds for burial, simply decided not to claim the body.

Trina Dow, director of victim services at the Anti-Violence Partnership, said she often sees victim assistance fall short for families who need it most. For example, she said, a family may seek relocation assistance if someone is killed in or near their home. The payout is up to $1,000 per victim, but whether that's sufficient often depends on whether the program counts only the deceased or also the survivors living in the residence.

"If you're living paycheck to paycheck or on welfare, you can't afford to move [with only $1,000]. So you're at risk. There are families that are in that situation."

Last year, her agency helped 77 families file homicide-related claims; 29 were awarded, three were denied for reasons related to illegal activity, and most of the rest are still in process.

"When you deny it, often it's the families and the children that suffer," she said. "A year or two ago, there was some discussion about possibly reimbursing families for funeral expenses, even when the victim may not have been innocent. But that was probably controversial."

So far, no such change has been made.

Instead, Sabrena Tucker, 47, felt that after her son Richard was killed two years ago, her family was treated like criminals rather than victims. Police still have not arrested anyone in the broad-daylight shooting outside her North Philadelphia home. But after she applied for compensation, they determined that her son had been involved in drug dealing that had caused his death. (A Philadelphia police spokesman said the investigation remains active, but declined further comment.)

Tucker said that Richard, 21 and a father of two young children, smoked marijuana but did not sell drugs of any kind. On the contrary, she believes he was killed because he was interfering with drug dealers' business by trying to keep criminal activity off of the block.

It cost $7,000 to bury him. She had to borrow all but $500 of that.

"My kids were out taking donations and asking people for help so we could bury my son. I just want to pay back some of these people," she said. "And I would like to get my son a plaque instead of that little piece of wood on his grave site. Without that, I don't know where my son is buried at."