Impact of John Paul II still debated

N OCT. 16, 1978, AT 6:18 P.M., puffs of white smoke erupted from a chimney atop the Vatican's Sistine Chapel.

ON OCT. 16, 1978, AT 6:18 P.M., puffs of white smoke erupted from a chimney atop the Vatican's Sistine Chapel.

In St. Peter's Square, more than 100,000 people cheered as Cardinal Pericle Felici of the College of Cardinals appeared at a balcony.

"Habemus papam!" he declared - "We have a pope!"

The crowd roared again.

Then Felici announced the new pope's identity: "Cardinale Karolum Wojtyla."

The roaring paused.

"Voy-TEE-wa?"

That wasn't Italian.

The crowd stood dumbfounded until someone recognized the name. "Il Polacco!" a voice cried. "The Pole!"

The words zigzagged through the crowd, which roared again as it grasped their stunning implication: Karol Jozef Wojtyla, the 58-year-old archbishop of Krakow, Poland, had been named the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

Cardinal John Krol, the Polish American archbishop of Philadelphia, was later credited with touting his friend's candidacy at the conclave, which elected Wojtyla on the second day of balloting.

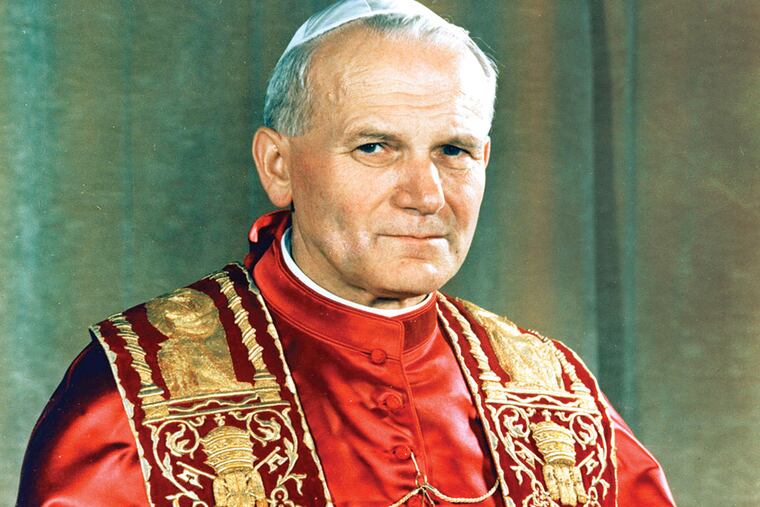

Plucked from what he described as a "faraway nation," the ruggedly handsome Pope John Paul II could scarcely have imagined that he was embarking on the third-longest pontificate in history - and the road to sainthood.

During the next 26 years, he would revamp canon law, survive two gunshot wounds, profoundly shake the "rotten tree" of communism, proclaim a record 483 saints, issue 14 encyclicals and a new catechism, forgive his would-be assassin, reach out in unprecedented ways to Jews and Muslims, and undertake 104 pontifical visits abroad, making him the most evangelical pope the church had ever seen.

And when, on April 2, 2005, he succumbed at 84 to heart failure and infection, more than a million people poured into St. Peter's Square to bid farewell.

"He hasn't gone yet. He's still guiding us," said Pedro Paul of Caracas, Venezuela, one of countless young people who stood hours for a glimpse of the pope lying in state.

"Sainthood now," some in the crowd cried out as he was laid to rest April 8 in a crypt beneath the basilica.

Now, just nine years later, their wish has been granted.

On Sunday, in St. Peter's Square, Pope Francis formally proclaimed John Paul and Pope John XXIII to be of such holiness and "heroic virtue" that their places in heaven are assured, and declared them saints of the Catholic Church.

John Paul's was one of the fastest tracks to sainthood in church history. Even Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who died in 1997, still awaits canonization.

A hero to many for his traditionalist views, the pope was a source of frustration for those Catholics seeking a more tolerant approach to same-sex marriage, contraception, in-vitro fertilization, and divorce and remarriage.

Yet progressives cheered his passion for immigration reform and worker rights, and his denunciations of capital punishment, capitalist excess, and war, which he called "always a defeat for humanity."

"I think that in his own mind, John Paul was trying to maintain a balance between continuity with the past while opening up the church to a real dialogue with the modern world," theologian William Madges of St. Joseph's University said recently. "But he was not about to abdicate church teaching to the current world."

Among the hallmarks of his pontificate were his efforts to bridge long-standing differences between Roman Catholicism and Judaism, Islam, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism. In 1986, he became the first pontiff to visit a synagogue, and in 1994 he ignored his own secretary of state and established full diplomatic relations between the Vatican and Israel.

And yet, Madges noted, he was not as willing to dialogue with liberal reformists within the church.

He vigorously asserted the church's long-standing argument that Jesus did not envision women priests, and in 1994 declared the teaching was infallible and closed to debate.

With the assistance of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and later Pope Benedict XVI, John Paul also disciplined scores of theologians for perceived unorthodoxy.

"Outside the church, the democrat," John Allen, longtime Vatican reporter for the National Catholic Reporter, once observed. "Inside the church, the autocrat."

Most papal scholars agree that his iron will was forged by his experiences in occupied Poland. Persecuted first by the Nazis in World War II and by a communist government for decades afterward, the Polish church demanded rigorous obedience from its members.

Theologian Stephen Schneck of the Catholic University of America also surmised that his sometimes authoritarian ways were driven in part by fears that contemporary notions of collegiality and decentralized authority, as envisioned by the Second Vatican Council of 1962-65, would weaken the church.

And yet John Paul's pontificate "changed the institution of the papacy," said Schneck, director of the university's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies. "With John Paul II, the pope becomes an international moral leader. He led us to believe the pope should be a charismatic personal pastor to all of us internationally."

John Paul also "really advanced the church's political and cultural engagement with the modern world," Schneck said, and laid the groundwork for the church's "contemporary emphasis on the sanctity of life and the dignity of the human person," because these "sprang from his own theology."

Whether his pontificate was too insistent on obedience and orthodoxy remains a matter of debate. During his 26 years of leadership, the Catholic Church saw sharp declines in Mass attendance and religious vocations in Europe, North America, and parts of Latin America. But the church has flourished in much of Africa, which he visited 14 times.

He was also criticized for failing to respond vigorously to the clergy sex abuse scandals that rocked dozens of U.S. dioceses late in his pontificate, by which time he was in poor health.

And yet, 16 years into his pontificate - with 10 more to go - John Paul's biographer, George Weigel, would argue in a column in The Inquirer that his subject's many accomplishments had already earned him the right to be remembered as "Pope John Paul II the Great."

It was an honorific some in St. Peter's Square were already crying out - "Magnus!" - as his coffin was being lowered into its crypt nine years ago.

Perhaps it is a too-grandiose title - one he would shrug off.

But now he will forever wear the greatest honor the Catholic Church can bestow: a halo.

856-779-3841

@doreillyinq