An anarchic talent: Robert Rauschenberg, 1925-2008

He combined real objects with pigment, creating improbable combinations and changing the direction of art.

Robert Rauschenberg, who with contemporary Jasper Johns provoked a profound shift in 20th-century art after World War II, died Monday night at his home on Captiva Island, Fla. He was 82. According to his New York dealer, Arne Glimcher of PaceWildenstein gallery, the cause was heart failure.

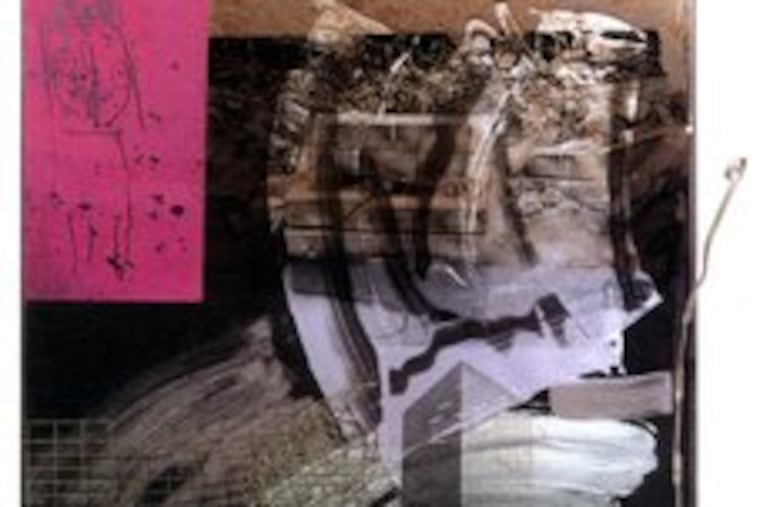

Beginning in the early to mid-1950s, Mr. Rauschenberg extended the vocabulary of painting, which had been more or less fixed since the Middle Ages, by combining pigment with real objects such as stuffed birds, fabrics and household appliances, and photographs reproduced from newspapers.

He did the same for sculpture, often placing so-called "found objects" in improbable combinations. One of the most memorable of these was a stuffed angora goat with an automobile tire circling its middle, which he titled Monogram.

Another landmark work, Bed, consists of a real pillow and quilt fixed to a wooden panel, and embellished with expressionistic drips and splashes of pigment. Now in the Museum of Modern Art, this work is perhaps the most famous of the artist's so-called "combines" - multimedia creations that established a new way for artists to compose.

Mr. Rauschenberg began his career in the late 1940s as a painter. He quickly began to challenge the dominant aesthetic of that period, abstract expressionism, which attempted to represent on canvas deep emotional and psychological currents.

Mr. Rauschenberg was more down-to-earth, a smasher of idols and flouter of convention, who once erased a drawing by leading abstractionist Willem de Kooning (with his acquiescence). That act alone signaled that contemporary art was off on a wild ride that rejected the heroic posturing of abstract expressionism in favor of improvisation and tangible connections to daily life.

Mr. Rauschenberg accomplished this by pushing painting and photography into a symbiotic relationship that over the decades has come to be recognized as his distinctive strategy. He would continue to produce such works in different media and at larger and larger scale well into his mature years.

The best of them, though, are the early ones, which even after a half-century retain their revolutionary spirit. Later variations on the photo-collage method, some on metal plates, are more commercial, spit-polished to the point where they seem attenuated and mannered.

Although Mr. Rauschenberg's art hadn't advanced significantly, if at all, since he moved to Florida in 1970, he'll be remembered as a genuine trailblazer, someone who opened up several pathways beyond abstract expressionism that many artists continue to follow.

He has been described as an early Pop artist, but that is misleading. He shared with Pop a willingness to use real objects and incorporate historical events into his art, but unlike hard-core Pop artists he wasn't ironic or satiric. He simply tried to make art more democratic and adventurous and less sacrosanct. For better or worse, we live with the consequences.

As he once observed: "Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two.)" And: "Any incentive to paint is as good as any other. There is no poor subject." Finally: "A pair of socks is no less suitable to make a painting with than wood, nails, turpentine, oil and fabric."

Sadly, the anarchic energy and subversive daring of his early work, which rejected precision, fussiness and preciousness, eventually ran dry. With the help of studio assistants, he continued to produce extended suites of images, including one that stretched more than 1,000 feet and filled an entire New York gallery building.

Although he has sometimes been compared to Pablo Picasso, the 20th-century's reigning genius, he wasn't sufficiently protean, as Picasso was, to periodically change direction or invent new artistic dialogue. His edge eventually disappeared, to be replaced by sleekness.

Born Milton Rauschenberg (he renamed himself as an adult) in Port Arthur, Texas, on Oct. 22, 1925, he began to draw while serving as a Navy medical technician during World War II. After the war, he attended the Kansas City Art Institute on the GI Bill, and then traveled to Paris for further study. There he met Susan Weil, whom he married in 1950. They had a son, Christopher, who survives, before divorcing two years later. A companion, Darryl Pottorf, also survives.

Mr. Rauschenberg also studied with Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. It's difficult to imagine an odder couple than the doctrinaire, disciplined Albers, famous for his color theories, and the anarchistic young Mr. Rauschenberg. Years later, though, the artist remembered Albers as "a beautiful teacher."

He achieved his breakthroughs in New York City during the 1950s. There he met Johns, who had developed his own distinctive way of incorporating objects into paintings. The two became close and, for a time, developed in tandem, like Picasso and Georges Braque when they invented cubism. However, in this case each maintained his separate style and thematic interests.

Mr. Rauschenberg's move to Captiva Island on Florida's Gulf Coast, which reflected financial prosperity, marked a shift to a more industrial scale of working. His main studio, one of nine buildings on his property, enclosed 17,000 square feet of working space.

On Captiva, he developed such grandiose projects as the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (ROCI), which involved visits to a number of countries around the world. Images he gathered in these places were transformed into a series of collage-style works on metal plates using vivid encaustic pigments.

He financed this venture himself to the tune of $5 million, but the results were disappointing, more self-aggrandizing than insightful about foreign cultures. With the ROCI project, the artist had become an orchestrator for a platoon of assistants.

Yet his early spinning-straw-into-gold approach, his willingness to use plebeian materials such as earth and metal junk, and his delight in making art that was crude and messy rather than elegantly finished remains refreshing, and assures him a prominent place in art history.

As he once said: "A lot of people try to think up ideas. I'm not one. I'd rather accept the irresistable possibilities of what I can't ignore. I think you're born an artist or not. I couldn't have learned it. And I hope I never do because knowing more only encourages your limitations."