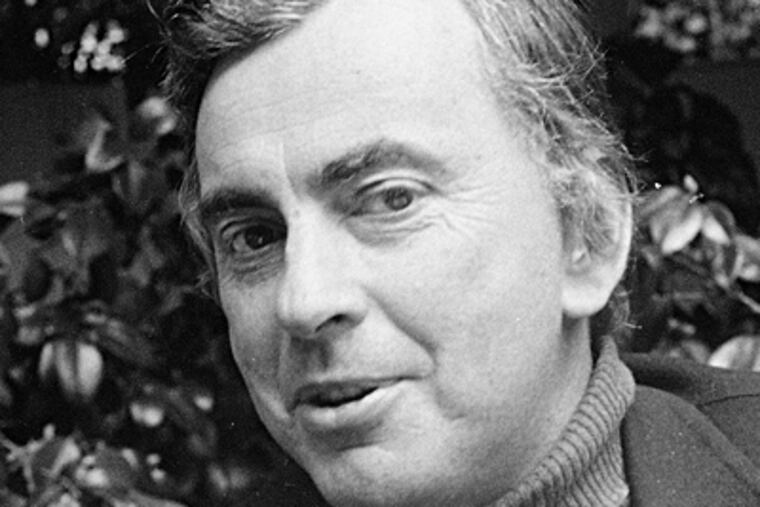

A superb stylist and iconoclast

LOS ANGELES - Gore Vidal, 86, the iconoclastic author, savvy analyst, and glorious gadfly, died Tuesday at his home in the Hollywood Hills from complications of pneumonia, his nephew Burr Steers said.

LOS ANGELES - Gore Vidal, 86, the iconoclastic author, savvy analyst, and glorious gadfly, died Tuesday at his home in the Hollywood Hills from complications of pneumonia, his nephew Burr Steers said.

Impossible to categorize, Mr. Vidal was a literary juggernaut who wrote 25 novels and volumes of essays that critics consider among the most elegant in the English language. He wrote Broadway hits, Hollywood screenplays, television dramas, and a trio of mysteries still in print after 50 years.

He popped up in movies, playing himself in Fellini's Roma, a sinister plotter in the sci-fi thriller Gattaca, and a U.S. senator in Bob Roberts. And he made two entertaining but unsuccessful forays into politics, running for the Senate from California and the House from New York.

In spare moments, he demolished intellectual rivals such as Norman Mailer and William F. Buckley Jr. with acid one-liners, establishing himself as a peerless master of talk-show punditry.

"Style," Mr. Vidal once said, "is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn." By that definition, he was an emperor of style, sophisticated and cantankerous in his prophesies of America's fate and refusal to let others define him.

In 1993, Mr. Vidal won the National Book Award for his massive United States Essays, 1952-1992, a collection of erudite and infuriating critiques on politics, sexuality, religion, and literature.

Threaded throughout his pieces are anecdotes about famous friends and foes, including Anaïs Nin, Tennessee Williams, Christopher Isherwood, Orson Welles, Truman Capote, Frank Sinatra, Jack Kerouac, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Eleanor Roosevelt, and a variety of Kennedys. He counted Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Al Gore among his relatives.

Mr. Vidal began his public life at 22 when his first novel, the World War II-themed Williwaw, won the wide admiration of critics. Two years later, the literary golden boy became an outcast with The City and the Pillar (1948), one of the first mainstream novels to deal frankly with homosexuality.

Ignored by book critics for several years, he turned to television writing, churning out dramas for prestigious showcases such as Suspense, Goodyear Playhouse, and Studio One. He adapted one of these works, Visit to a Small Planet (1957), for the stage. A Cold War parable featuring a space alien who provokes war between the United States and the Soviet Union, it ran on Broadway for 388 performances and was made into a movie starring Jerry Lewis.

Mr. Vidal's other major critical and commercial success as a playwright was The Best Man, a 1960 political drama that starred Melvyn Douglas as a high-minded presidential candidate modeled on Adlai Stevenson. After a 520-show Broadway run, it was made into a 1964 movie starring Henry Fonda, and a revival is now on Broadway.

Although Mr. Vidal often declared the novel as a literary form dead, he wrote more than two dozen of them. He called books such as Burr (1973), Lincoln (1984), and Julian (1964) "meditations on history and politics."

Exploring the complexities of power and those who seek it, they were written, Mr. Vidal said, "to correct bad history," but some critics said he was the guilty one.

"Inventions" was his term for his wilder fiction, including the comic novel Duluth (1983) and the wicked spoof featuring transsexual Myra Breckinridge in the novel of the same name. Some critics consider Myra Breckinridge (1968) his masterpiece.

An insider by dint of his connections in Washington, Hollywood, and literary salons around the world, Mr. Vidal acted more as the outsider.

He wrote a lengthy defense of the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh in a 2001 Vanity Fair article. McVeigh had struck up a correspondence from prison after reading a piece by Mr. Vidal on the erosion of the Bill of Rights in the federal attack on the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas. The two men remained in contact for three years, until McVeigh's execution.

A fierce critic of the United States as a "national security state," Mr. Vidal seemed to move further into the political wilderness after the 9/11 attacks, suggesting that the George W. Bush administration had colluded with the terrorists. His views turned many longtime admirers into detractors, including writer Christopher Hitchens, who denounced him as a crackpot.

"Gore was an iconoclast. That was his strength," former Nation editor Victor Navasky told the Los Angeles Times several years ago.

Mr. Vidal crafted many of his diatribes at his villa in Ravello, Italy, where he lived for three decades. In 2005, he returned full-time to his other longtime home, a mansion in the Hollywood Hills.

Mr. Vidal had a lifelong fascination with Hollywood as a place of invention and reinvention, the chief motifs of his unusual life.

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal was born on Oct. 3, 1925, in West Point, N.Y. His father, also named Eugene, was an aviation expert who taught at the U.S. Military Academy and later served as director of air commerce under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His mother, the former Nina Gore, was a Washington socialite whom he portrayed as a heavy drinker with a nasty temper. They divorced when Mr. Vidal was 10. His mother was briefly married to Hugh Auchincloss, who later married Jacqueline Onassis' mother.

A complete list of survivors was not available, but his nephew said they include a half-sister and a half-brother.

Because of his poor relationship with his mother, Mr. Vidal spent much of his childhood in Washington with his maternal grandfather, Sen. Thomas P. Gore, an influential Oklahoma Democrat.

Mr. Vidal graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in 1943, skipped college, and joined the Army, serving on a freight-supply ship in the Aleutian Islands. There he became familiar with the sudden blasts of wind called williwaws. During night watches in port, he began to write Williwaw, which earned flattering reviews and established its young author as a leading member of the post-World War II class of first-time novelists that included Mailer and Capote.

His semiautobiographical The City and the Pillar centered on two athletic, boy-next-door-types who become lovers. It was inspired by Mr. Vidal's love for schoolmate Jimmie Trimble, who died while serving in the Marines at Iwo Jima. Mr. Vidal said he did not realize until decades later that Trimble had been "a completion of myself," the genuine love of his life.

Although commercially successful, the book closed the door on Mr. Vidal's political ambitions and made him a literary persona non grata. To survive financially, Mr. Vidal wrote several books under fictitious names, the most successful of which were the three mysteries he wrote as Edgar Box.

Mr. Vidal also turned his talents to screenplays, which included his successful adaptation of Tennessee Williams' Suddenly, Last Summer. He was an uncredited writer on the 1959 blockbuster Ben-Hur, contributing what he described as a homoerotic subtext to the relationship between Judah Ben-Hur and Messala.

In 1960, the same year that The Best Man opened on Broadway, Mr. Vidal ran for a seat in the House as a liberal Democrat in a conservative upstate New York district. Not surprisingly, he lost.

Two decades later in California, he trailed Jerry Brown by a large margin in a bid for the 1982 Democratic nomination for a Senate seat.

Mr. Vidal was far more successful writing about political power than acquiring it. His first historical novel was Julian (1964), a bestseller about the fourth-century Roman emperor who rejected Christianity. Praised as a vivid evocation of the era, it freed Mr. Vidal from literary Siberia. He went on to reimagine American history in Washington, D.C., Burr, 1876, Lincoln, Empire, Hollywood, and The Golden Age.

Among the most controversial was Lincoln, which portrayed the 16th president as a devious and possibly syphilitic leader who cared more about preserving the Union than ridding it of slavery.

"I am at heart a propagandist, a tremendous hater, a tiresome nag, complacently positive that there is no human problem which could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise," he said in Gore Vidal: A Biography (1999) by Fred Kaplan.

Despite his crushing forthrightness on many topics, Mr. Vidal preferred ambiguity in the personal realm.

Mr. Vidal, who was never married or had children, wrote in his memoirs about sexual contacts with men, including Kerouac. But, to the dismay of gay activists, Mr. Vidal rejected efforts to put him in any sexual category. He was famous for proclaiming that "there are not homosexual people, only homosexual acts."

His companion of 53 years was Howard Auster, whom he met in New York in the 1950s when Auster was a singer trying to get a job in advertising. Mr. Vidal described their relationship as platonic and said "no sex" was the reason for its longevity.

Auster died in 2003 and was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, "as I shall be in due course," Mr. Vidal wrote, "when I take time off from my busy schedule."