Reconnecting with letters from WW2

Hundreds of letters filled the dusty box. The faded words professed everlasting devotion and longing for an eventual reunion. It was hard to imagine that my mother- and father-in-law had written such words, and written so often to each other. Their love l

Hundreds of letters filled the dusty box. The faded words professed everlasting devotion and longing for an eventual reunion. It was hard to imagine that my mother- and father-in-law had written such words, and written so often to each other. Their love letters sent across the Atlantic Ocean during World War II are sweet, even if they aren't a significant historical find. But I must admit that, after reading just a few, the novelty wore off. I knew that their story had a happy ending and that Ray and Margaret Ann Lehman went on to celebrate their 70th wedding anniversary.

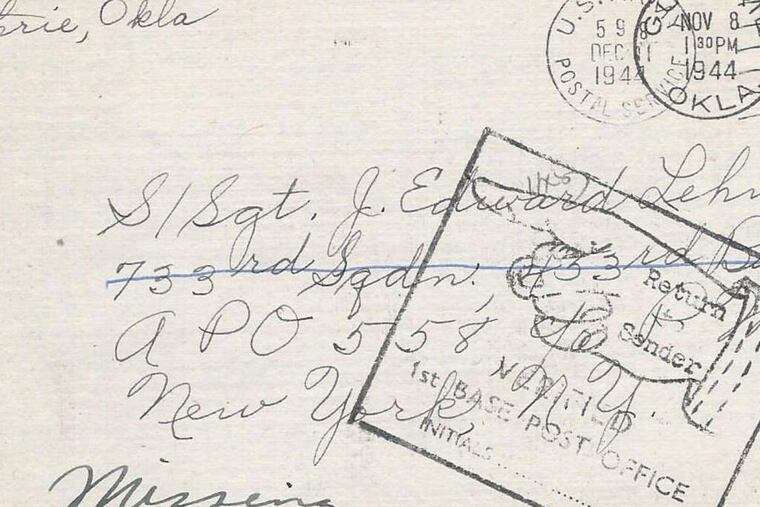

As I gathered the bundles to put them away, another envelope caught my eye. Return to Sender was stamped boldly across the front, and seeing the word missing scrawled under the address sent a shiver down my spine. There were only a few of these letters, but I realized that they were written by Ray's mother to his brother Edward, who was also serving overseas. These were a different kind of love letter, one that can only exist between a mother and son. They were devoid of endearments and promises, but the simplicity of their content expressed the great concern they had for each other.

Edward Lehman was the oldest of five children and upon his father's death became "the man of the house" at age 11. From early on, he felt a tremendous responsibility to his mother. Descended from a long line of pacifist Mennonite ministers (his great-great-grandfather fled Germany to avoid involuntary conscription), he was a conscientious objector but enlisted in the Army after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

He kept the content of the letters to his mother reassuring and light, describing the beautiful scenery, and how funny the dignified officers looked riding on those high bicycles. He also kept track of what was going on at home and once asked his mother if his uncle had ever traded that Studebaker for a Ford.

Ruth Lehman, widowed at age 32 with five children aged 2 to 11, was a schoolteacher. During World War II, all four of her sons served in the military. That autumn of 1944, she paced her letters carefully, as if she wanted to avoid conveying an expectation of increased correspondence from her son. Ruth's letters updated Edward about the latest news of the people and place he left behind. She loved him enough not to express worry or the empathy she felt as he battled not just against the enemy but his own antiwar convictions. Even when weeks went by without a letter from him, she kept her tone light, not expressing her concerns on paper.

In our time of instantaneous communication, it's hard to imagine pulling paper from a drawer, handwriting a letter, let alone waiting for the postal service to deliver it across the ocean and through the battlefields. It took weeks, if not months, for letters to reach their intended recipients. How must Ruth have felt when her letters to Edward were returned unopened? To learn that he was missing, not knowing anything, and having no way to find out?

The last letter Ruth wrote to Edward was addressed to her son as "United States Prisoner of War in Germany c/o International the Red Cross." She still spoke pleasantries: that a neighbor brought her a Christmas tree and that Uncle Marcus sold his store. But her worry is palpable. She writes, "Be sure that each morning and evening as well as at times through the day, a prayer goes up that you may be given courage to face whatever befalls you as a true Christian should."

This final letter was never mailed. She likely received the notice of his death before posting it.

The details are sketchy: Did he die when his B-24 was shot down? Did he ever actually become a prisoner of war? Though his mother traveled to meet the families of his fellow crew members, four of whom were POWs who eventually returned home, she never found out for sure. She knew Edward was buried in an American cemetery in France, but was never able to make the journey to visit his grave.

When we were young, we didn't think much about our family history and those who came before us. As we were growing up, we never took the time to ask them to talk about their lives. It is only when we grow older that we realize we squandered an opportunity to learn the details of our family's past. Now, the storytellers and their stories are gone.

The only tangible pieces of Edward that remain are these letters, some photographs, and a rolled-up certificate signed by Franklin Roosevelt acknowledging the supreme sacrifice he made for his country. Who was he? What was he like? I'll never really know.

There's no tangible evidence of Ruth's pain, yet I can experience parts of it. Any mother of a son knows that there is an intense connection to that little boy who once loved her more than anyone or anything in the world. It remains part of her, even when that son moves on with his own life.

Edward and Ruth are gone. I never knew them and I don't know all the details of their lives. Yet a residue of their love for each other remains. It is in the pain Ruth felt when her letters were returned, and in the fear that must have crushed her chest when she saw that word missing. It is all still there, even though stored away in an attic for 70 years.

Christine Carlson is a communications executive in Center City