The long road from 'let me die'

Michael Vitez is employed by Temple University as director of narrative medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine Three weeks after the crash of Amtrak Train 188, Aaron Levine, 80, woke up in Temple University Hospital's intensive care unit.

Three weeks after the crash of Amtrak Train 188, Aaron Levine, 80, woke up in Temple University Hospital's intensive care unit.

He was on a ventilator. He had nine broken ribs, which had punctured his right lung, collapsing it. The area around his lung had filled with blood. He took so long to wake up, doctors had worried about brain injury.

Unable to speak because of the breathing tube, he mouthed the words to family, nurses, doctors, everyone:

"Let me die."

Levine, one of 238 passengers, was a personal-injury lawyer who lived in Washington. He had spent the last 50 years suing hospitals, doctors, and drug companies. He had no confidence in medicine's ability to bring him back.

Amy J. Goldberg, a trauma surgeon at Temple for 23 years, who had spent three weeks fighting to save him, stood at his bedside.

"I hope you have a good lawyer," he told her, mouthing the words. "You're going to need one."

The train derailed about 9:30 p.m. on May 12 last year. Levine and his wife, Barbara, 78, were on their way to New York for the Frieze art fair.

They were riding in the quiet car, the second car, in the last seat, facing Washington. Aaron was against the window, his wife next to him.

"I got thrown to the other side of the train," said Barbara. "I was screaming for him, but there was no answer."

"I had five cracks in my pelvis," she added. "They took me in a police van to Hahnemann. You know the potholes in the road? I could have had 10 more cracks in my pelvis." She still had her phone and called her son, Andrew, a physician in Manhattan.

He got to Temple by midnight.

"There was a whole trauma team around him with 10 bags of different blood products, IV medications," recalled Andrew. "He looked like death. He was sedated. On a respirator. His face was bruised and swollen."

The son paused, overcome with emotion.

"He was on blood thinners already because he'd had a small stroke five years ago. So he probably almost bled to death. When I saw him in the trauma bay, my first instinct was it's all over."

Awakening

Aaron Levine survived that first night.

Barbara Levine was transferred the next day to Temple, down the hall from her husband and the ICU.

After five days, she was discharged, got a wheelchair-accessible hotel room in Center City, and went to Temple every day.

Aaron Levine presented an immense medical challenge. So many things were working against him - his age, the severity of his injuries, the fact that he was on blood thinners.

After two weeks, doctors tried bringing him out of an induced coma, but he didn't wake up.

When he finally did, he thought he'd never again have a life worth living.

Levine told his son to look up the Oregon assisted-suicide law, "because I planned to go there."

Andrew refused.

The three children were adamant. This wasn't cancer. This was trauma, and he could recover.

Aaron Levine's desire to die made it difficult on doctors, who had worked so hard to save him.

"We were really challenged by that," said Goldberg.

He weighed 191 pounds on admission. Even with a feeding tube, six weeks later, on June 23, he was 143.

One thing he always looked forward to was physical therapy.

On June 1, he sat on the side of the bed for 10 minutes. On June 5, he stood for a moment. By June 18, he could sit in a chair.

"They were like a cheering squad," he said of his therapists.

As he gained strength, Levine started making jokes. Staff may not have loved his jokes but loved that he was making them. Carrie Dempsey, one of his physical therapists, was pregnant, and when she'd leave early for a doctor's appointment, he'd ask the next day, "How's the baby?"

In early July, staff clapped when he walked out of his room for the first time, wheelchairs in front and behind, therapists on each arm.

Finally, by July 8 - 57 days since the crash - he was off the breathing machine for good, able to eat a pureed diet. He was 132 pounds.

Every other Amtrak patient was long gone.

By mid-July, even Barbara Levine had reached her limit.

"On the corner by the hotel is a Rite Aid," she recalled. "A bag lady was sitting outside the drugstore all the time. She'd been watching me go from a wheelchair to a walker to a cane. One day she said to me, 'I can't believe what progress you've made.' I knew it was time for us to go home."

'A miracle'

That day came July 28. Aaron would go by ambulance to a rehabilitation hospital in Washington. He was still frail - in his own words, "decrepit."

It was an anxious moment, but a triumphant one. "A miracle," said his wife. Shirley Defrehn, the case manager, cried.

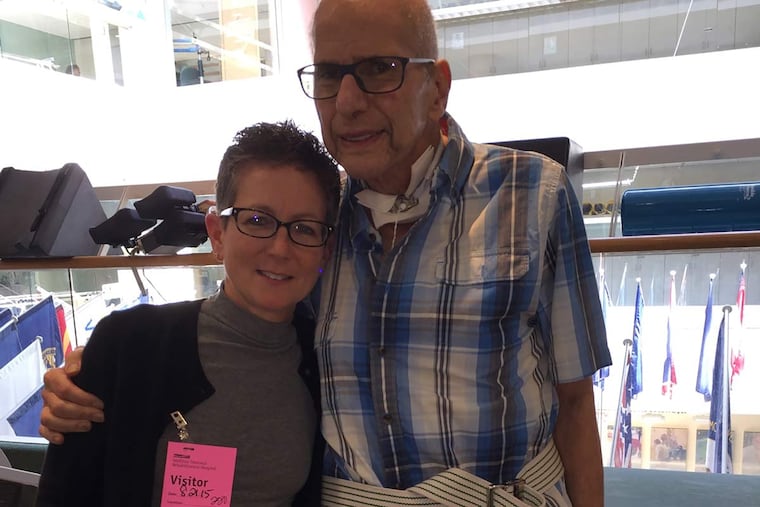

In August, Goldberg went to Washington to consider a new blood refrigerator for the operating room. She visited the patient who had once threatened to sue her.

"Dr. Goldberg was wonderful," Levine says now. "She saved my life. She called the shots."

In December, Aaron Levine sent a case of champagne for the holidays to Defrehn and told her to give bottles to the physicians, nurses, and therapists who had helped him heal. Defrehn kept one for herself but won't drink it. Goldberg won't drink hers, either. They want to keep that bottle to remember.

A year after the crash, Levine is home and working again, though he can't try cases anymore or go to court. He can't walk two blocks without resting. He still needs therapy at home.

The Levines have returned to New York a couple of times to see art. With one exception.

"We don't take the train anymore," he says. "We hire a driver."

Michael Vitez is employed by Temple University as director of narrative medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine. He retired from The Inquirer in 2015 after 30 years of service.