Inquirer editorial: Chaka Fattah and his forgiving friends

How did a veteran congressman come to think it was a good idea to appropriate half a million federal dollars to a fake charity devoted to cleaning up after water-skiers? Or take a down payment on a vacation home from a would-be ambassador whose bona fides he pitched to the president himself? Or repay an illegal loan to his campaign with laundered public money?

How did a veteran congressman come to think it was a good idea to appropriate half a million federal dollars to a fake charity devoted to cleaning up after water-skiers? Or take a down payment on a vacation home from a would-be ambassador whose bona fides he pitched to the president himself? Or repay an illegal loan to his campaign with laundered public money?

The answer can be discerned in the collective shrug of Chaka Fattah's fellow Philadelphia Democrats last week when a jury found him to be the taxpayer-employed capo of a criminal organization. The congressman's entire peer group appeared to share his assessment that his 22-count federal conviction amounted to a regrettable misunderstanding. Judging by their reluctance to utter even the mildest condemnation of his crimes or suggest he no longer deserved to hold public office as a result, Philadelphia's Democratic establishment has been crooked so long that it looks like straight to them.

Presiding over this mutual forgiveness society is Bob Brady, Fattah's longtime congressional colleague and the city's Democratic Party boss. Having endorsed Fattah's bid for reelection even as his trial loomed, Brady was hardly going to change his mind just because his fellow congressman was convicted of stealing public money, unable to vote under House rules, and probably headed to prison. Rather, he opted for the tried trope of regarding the consequences of Fattah's willful crimes as a freak tragedy akin to a tornado or terminal disease. "It's a shame to have something like this happen," Brady told the Inquirer.

Meanwhile, Mayor Kenney, rather than signal disapproval of serious crimes or public officials who commit them, resorted to an oddly anodyne recitation of facts: "The jury spoke, and the criminal justice system went forward," he noted wanly.

Even Dwight Evans, who personally prevented Fattah's reelection to a 12th term by winning the Democratic primary in April - and who has assembled a strikingly Fattahvian collection of pet charities - mustered no talk of ethical standards, instead joining Brady in lamenting a "sad day" for Fattah and his family.

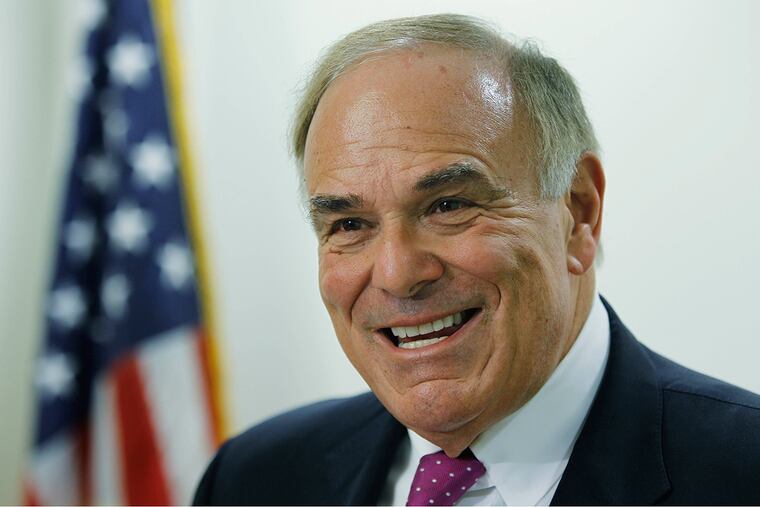

The elder statesman of this corrosive laissez-faire philosophy is of course Ed Rendell. While testifying for the man who gave the Fattah family $18,000 ostensibly for a Porsche - except that the Fattahs mysteriously retained possession of said Porsche - Rendell accused the prosecutors of being "cynical." Politicians happen to have friends, the former mayor and governor remonstrated. "We're not all bad. We're not all evil."

Sure, but no one asked Rendell whether all politicians are bad - only whether one of them was.

But no less than one of the nation's highest-ranking Democrats, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, refused to admit that much, preferring to praise Fattah's service and declare his conviction "heartbreaking."

Heartbreaking? How about blood-boiling?

It's no wonder Fattah himself attempted to cling to office even as a convict, initially declining to resign and then offering to leave at a leisurely pace three months hence. When he finally quit under pressure from Congress' Republican majority, he did so in a letter singing his own praises, offering not a word of contrition, and thanking his colleagues - without whom none of this would have been possible.