America's long history of restricting immigrants

President Trump's recent moratorium on the entry of individuals from seven predominantly Muslim countries belongs to a dubious tradition of restrictive immigration practices stretching through America's past. For some historical perspective, consider the story of the 1917 Immigration Act, which went into effect a century ago today.

President Trump's recent moratorium on the entry of individuals from seven predominantly Muslim countries belongs to a dubious tradition of restrictive immigration practices stretching through America's past. For some historical perspective, consider the story of the 1917 Immigration Act, which went into effect a century ago today.

While much of Western Europe was busy at the outset of that year squandering its manhood in the trenches of France, the United States faced down its own problems. Economic insecurity transposed into the psychological sort, while the influx of southern and central European immigrants presaged in the minds of many a shake-up of the country's ethnic character.

To many Americans, these were not Emma Lazarus' "huddled masses." They were fifth columns on the march, here to steal a job, become a public charge, or - in the case of the anarchist followers of Luigi Galleani - commit "propaganda of the deed" via suitcase bombs.

Charlie Chaplin seized the zeitgeist with his 1917 film, The Immigrant, whose plot involves in part a penniless immigrant accused of thievery. (In one scene, the Tramp kicks an immigration officer, later used as evidence of Chaplin's anti-Americanism when his reentry visa was denied.)

"We ought to have our fences up," bellowed Idaho Sen. William Borah the year prior, "and be thoroughly prepared to protect those in this country who will be brought into competition with the hordes of people who will come here."

Then, as now, the rhetoric did not match reality.

To be sure, between 1900 and 1915 the nation admitted nearly 15 million immigrants. The First World War, however, had stanched the flow. In 1913, a year before the conflict's outbreak, immigration to the United States from Europe numbered more than a million souls. In January 1917, government mandarins forecasted for the following year only 300,000.

To the period's xenophobes - including the popular Immigration Restriction League - these were simply "alternative facts."

Founded by three Harvard graduates, the League had long advocated for a literacy test for immigrant hopefuls. Such legislation had in fact reached three presidents' desks, vetoed in turn by Cleveland, Taft, and Wilson (twice).

For Wilson, in his second term in 1917, the issue was clear. A literacy test "excludes those to whom the opportunities of elementary education have been denied, without regard to their character, their purposes, or their natural capacity."

With a two-thirds congressional majority, however, the 28th president's veto pen ran dry. On Feb. 5, "an act to regulate the immigration of aliens to, and the residence of aliens in, the United States" went into effect.

In many ways, it was an expansion of regulations already on the books, albeit with steeper fines (a doubling of the $4 head tax) and a broadened list of "undesirables" (alcoholics, homosexuals, epileptics, "professional beggars," polygamists, and other "persons mentally or physically defective.")

But the act staked new ground in two significant ways.

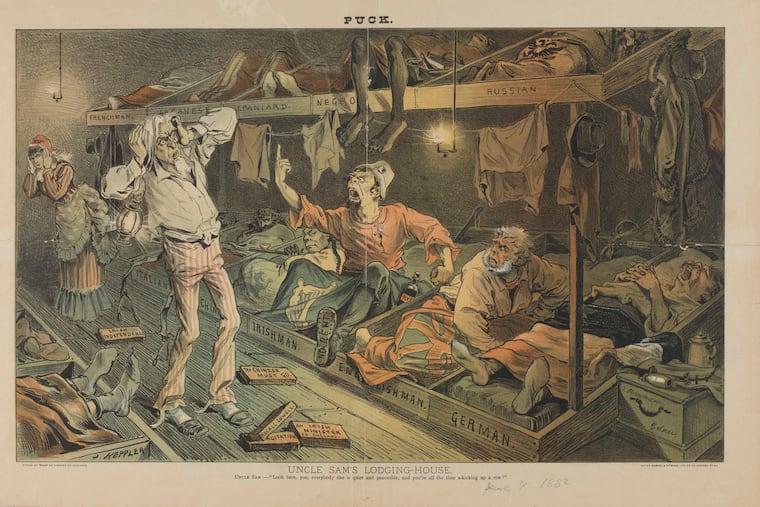

First, the barring of all immigrants more than 16 years old - regardless of national origin - unable to read 30 to 40 words in their native language. A popular political cartoon of the period depicted "The Americanese Wall," with pens protruding over the parapets.

Second, the act outright excluded those from the "Asiatic Barred Zone," i.e., much of South and Southeast Asia. Hitherto the "only" peoples denied entry were Chinese and Japanese.

Even with these new restrictions, immigrants continued to be likely suspects for seemingly every crime. In March, in the aftermath of the city's "bread riots," an investigation was launched into "whether foreigners in most cases have not led the riots."

The true culprit was that border-hopper extraordinaire: inflation.

The following month, the United States entered World War I and experienced an initial burst of ethnic cohesion. On Independence Day 1918, a "declaration of men of many races rightfully claiming to be Americans" was issued, signed by delegates ranging from Assyrian to Lithuanian.

Following the Treaty of Versailles, however, the number of immigrants to the United States once again began to climb. Increasingly draconian restrictions would follow in the 1920s, many of which would be in effect until the 1950s.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania's collections document more than 300 years of immigrant and ethnic experiences in the United States and are open to the public.