Jackson: 'No brag, just fact' should be Ali's epitaph

My admiration for Muhammad Ali wasn't at first sight. You have to understand that when Cassius Clay, which was his name at the time, knocked out Sonny Liston on Feb. 25, 1964, in my 10-year-old mind he was defeating a man admired by little black boys in A

My admiration for Muhammad Ali wasn't at first sight. You have to understand that when Cassius Clay, which was his name at the time, knocked out Sonny Liston on Feb. 25, 1964, in my 10-year-old mind he was defeating a man admired by little black boys in Alabama like me for his ferociousness in doing the inconceivable: routinely knocking out white men with no fear of being trotted off to jail. It didn't matter that Clay was black too. He was a loud mouth and too good-looking to believe he would hold the heavyweight crown for very long.

I changed my tune when Ali, who revealed his Muslim name after the Liston bout, again and again proved he was no fluke in the ring. In my last year of elementary school, however, Ali lost a different fight. He was denied the conscientious objector status he had sought to avoid being drafted. Ali said he believed that any war not declared by Allah violated the Koran. In 1967, Ali was convicted of refusing induction into the Army and professional boxing subsequently stripped him of his titles.

By the time Ali returned to fighting in 1970 (his conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1971), I was a teenager and began to see him as more than a boxer. I wasn't alone. By standing up for his beliefs despite being banned from boxing for three of his prime years, Ali became bigger than the sport. His willingness to risk his livelihood and speak his mind when others might let fear reduce them to timidity encouraged a generation that had learned from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to stand up when you think you're right. After King's assassination in 1968, many young African Americans were also drawn to the strident militancy and in-your-face attitude of the Black Panthers, whose philosophy in a sense matched Ali's punishing blows in the ring and outspoken behavior outside of it.

With each big fight, Ali became bigger than life, an icon not just in America but worldwide after promoters staged some of his biggest bouts overseas, including the "Rumble in the Jungle," fought in Kinshasa, Zaire, against George Foreman in 1974; and the "Thrilla in Manila," fought in Quezon City, Philippines, in 1975 against Joe Frazier. By then you could begin to see the end was near for Ali as a boxer. He retired after taking the heavyweight title back from Leon Spinks in 1978, who had taken it from Ali earlier that year. Ali returned to the ring in 1980, but he was no match for a much younger Larry Holmes. Ali's last fight was a loss to Trevor Berbick on Dec. 11, 1981. "I did good for a 40-year-old," Ali said afterwards. "Age is slipping up on me."

It's hard to watch sports heroes go out like that. I covered the last season of Paul "Bear" Bryant, who to this day is considered by many to have been college football's greatest coach. But his 1982 University of Alabama team finished the regular season with a dismal 7-5 record, including a bitter one-point loss to to arch-rival Auburn in the final game. Two weeks later, Bryant retired. I couldn't help thinking as I listened for the last time to his chain-smoking-induced gravelly voice that this man, whom even some Christian Bama fans said could walk on water, had been returned to mere mortality. He coached one more game, beating Illinois 21-15 in the Liberty Bowl. A year later, Bryant died at age 69.

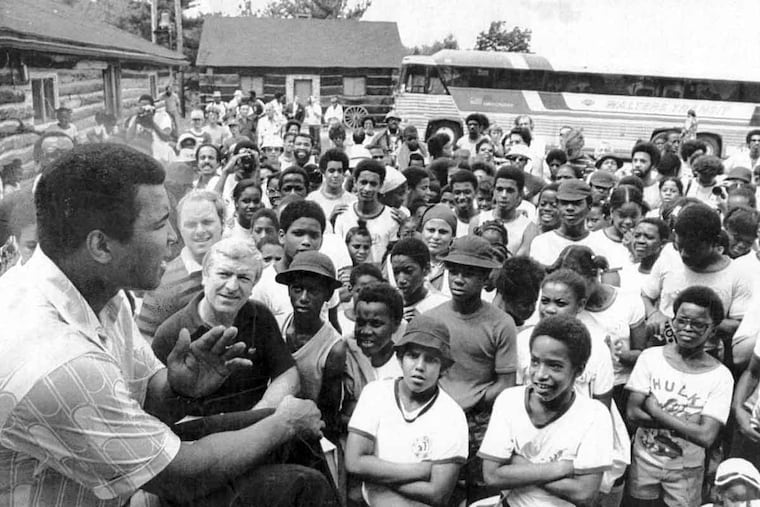

Given the way Ali's ring career ended, it wouldn't have been too great a stretch of the imagination at that time to see him follow the path of numerous has-been professional pugilists into eventual obscurity. But the man known as "The Greatest" wouldn't let retirement defeat him. Not long after he quit boxing, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. Still he refused to go down. Ali continued his financial success as a spokesman for sundry products and causes while giving considerable time and money to various philanthropies. Coming full circle from when he was prosecuted as a draft dodger, he was presented the Medal of Freedom in 2005 by President George W. Bush.

Ali, like any other mere mortal, had weaknesess. He was no more the perfect husband, father, friend, or Muslim than he was the perfect boxer. His defeats attest to that. But he was perfectly audacious. He would tell an opponent, often in rhyme, exactly what he planned to do to him, including the round he planned to do it, and frequently enough to make it uncanny carry out his plan. Will Sonnett, the fictional hero of a TV Western popular in the 1960s when Ali was rising to fame would similarly tell foes what he was capable of and end the conversation with the words, "No brag; just fact." What a perfect epitaph that would be for Ali.

Harold Jackson is editorial page editor for the Inquirer. hjackson@phillynews.com