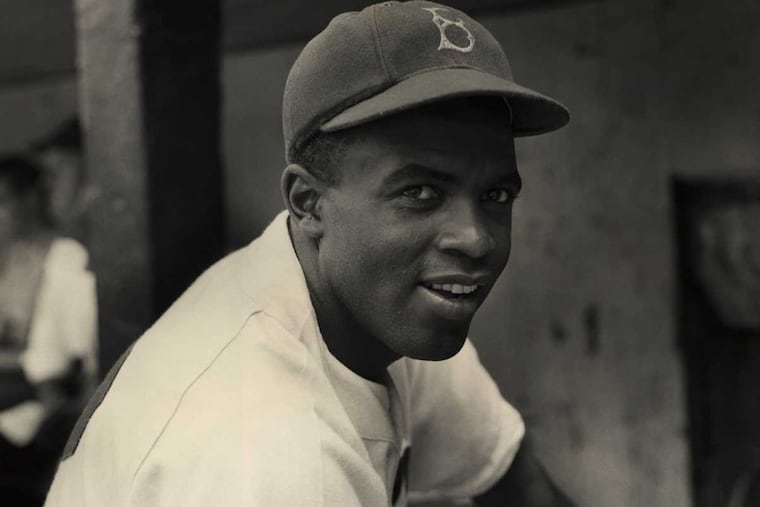

70 years later, Jackie Robinson still a hero

At the top of the seventh, we stood up to show our support for the Dodgers. We weren't alone -- practically all the African American fans were on their feet, too. "Why are they all standing?" I asked Dad. "Jackie Robinson," he said.

Wednesday, Sept. 27, 1961, was a big night in my life. I was going to my first major league baseball game.

It was my dad's birthday. And Uncle Jack's birthday. And my cousin Jay's 12th birthday - and this game was his present. The Phillies were playing the Dodgers, Jay's favorite team. Uncle Jack picked us up in his wood-paneled Ford station wagon. Both he and dad wore coats and ties - that's what men wore to the ballpark then. Jay and I wore what is now called "business casual."

The ride to Connie Mack Stadium from Drexel Hill was shorter than the trip to North Wildwood but seemed to take forever. Finally, we pulled up to a parking lot across from what looked like a factory building with a turret. "We're here," Dad said. Here where? I thought, having seen Yankee Stadium on TV. We're here at a factory with a turret on it.

Three miracles soon occurred. First, Uncle Jack successfully navigated the Ford into a parking lot with cars four inches away on either side, guided by a guy who kept waving him forward, oblivious to the fact that Uncle Jack was close to impaling him on the Chevy Impala taillights inches away from his behind. Somehow Uncle Jack stopped before killing him. Miracle No. 1.

At the same time, cars on either side of us did the same thing, lining up four inches away from each other. Somehow everyone got out without doors nicking cars. Miracle No. 2.

We crossed the street to the factory building, going through a turnstile and then an entryway. Beyond that was the greenest grass you ever saw. Miracle No. 3.

It was a horrific season for the Phils, who had lost 23 straight games that summer, so we had great seats behind the Dodger dugout on the first base side. It was the year of Mantle and Maris, but we were more than content with Johnny Callison and Tony Taylor. Only about 4,000 or so fans came that night, and I noticed that most of the ones sitting with us were African Americans, the men wearing the obligatory grownup coats and ties.

To Jay's dismay, Don Drysdale was not on the mound. Out of the speakers came the announcement, "Pitching for the, Dodgers, Sandy Koufax." Dad leaned over to us and said, "Watch this guy. You'll like him, Tim - he's a lefty like you." The Dodgers scored a run in the first, which made Jay happy.

Dad was right. Koufax was something, rocking back with a high kick, throwing a fastball that popped loudly into John Roseboro's catcher's mitt. At 10, I had my share of heroes: one dad, one grandfather, and President Kennedy. I now added one more. In the fifth, the Phils got two unearned runs to go ahead, but that was now bad news, not good.

In the bottom of the sixth, Koufax struck out Pancho Herrera (I know, who didn't strike out Pancho Herrera?), and the announcer informed us that "Sandy Koufax has just broken Christy Mathewson's National League record for strikeouts in a season." It was the first time I was part of a standing ovation.

At the top of the seventh, Jay stood up to show his support for the Dodgers. So did I. And we weren't alone - practically all the African American fans were on their feet, too. "Why are they all standing?" I asked Dad. "Jackie Robinson," he said.

Oh.

In the top of the ninth, Duke Snider pinch hit for Koufax. At 35, Snider was ancient, and Jack Baldschun quickly got two strikes on him. "You're all washed up, Duke," a tall African American guy wearing a fedora roared behind us, dropping his hands in disgust. Snider swung viciously and missed, kneeling on one knee as he whiffed. One out later and the game was over.

An interesting night. The best pitcher lost, the poorer team won, and I had just been introduced to race in America. Later, too keyed up to sleep, Dad and I talked about the game, and about the times he saw Jackie Robinson play.

A few days later, he came home with a book about him. The Civil War centennial was in full swing, but I read the Robinson book before devouring one on Lincoln. It fascinated me that the day Lincoln died - April 15 - was the same date that Robinson would later break the color barrier in the big leagues, in 1947. Add one more hero.

The following May, Dad and I headed to the ballpark. The Dodgers were in town; Koufax was pitching. I had decided my career path lay with the Dodgers, telling Dad on the way that Koufax was only 15 years older than me. If I made the club at 19 like he did, we'd be teammates. "We'll see," Dad said.

Once again we were behind first base. As batting practice ended, Dad pointed to two men in suits, standing by the Dodger dugout. "If you want to start collecting autographs," Dad said, "you might ask those gentlemen."

By the time I reached the dugout, one of them, Don Newcombe, was walking onto the field. But the other gentleman was still there. He was immense, with a shock of thick, graying hair, and the darkest skin I ever saw. It was him. "Can I have your autograph, please?" I asked. He nodded. In bold strokes he wrote, Jackie Robinson.

He didn't play in either of those games I attended. Jackie Robinson didn't have to. Homer was right, after all: "Achilles absent is Achilles still."

Even today.

Tim McGrath is the author of "Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America's Revolution at Sea." tmcgrath97@gmail.com