3 core principles emerge for free speech debates on campuses

In the current political climate, a "free speech" crisis - whether it's a controversy created by an outside speaker, a student, or a faculty member - brings enormous challenges for an institution.

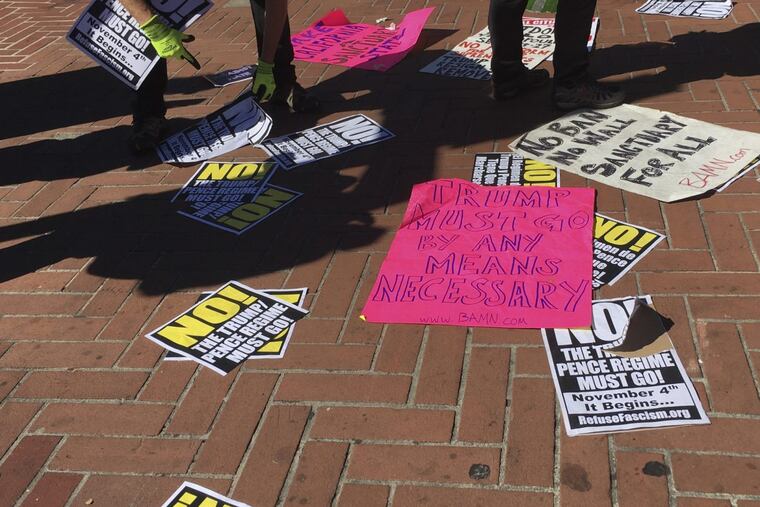

From Middlebury College in Vermont to the University of California at Berkeley, the issue of free expression on campuses around the nation has ignited a firestorm of protest and controversy.

Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., is one of the places where a free-expression controversy raged this summer, and where students, faculty, staff, and leadership are coming together to address the challenges head-on. At a recent forum on "Bridging Divides," the two of us participated in a campus conversation about the essential value of unfettered inquiry and debate as the heart of a liberal arts education.

As a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and editor and a free-expression scholar and former university president, we offered perspectives on a series of actual and hypothetical cases that face our colleges and universities today. The ensuing dialogue with the audience (which included "watch parties" for a live-stream broadcast, shared nationally with members and chapters of the Phi Beta Kappa Society) was lively and productive. It exemplified the kind of open and free-flowing community discussion that can enable colleges and universities to find ways to come together to develop core principles governing free expression before a crisis ever envelops a campus.

In the current political climate, a "free-speech" crisis — whether it's a controversy created by an outside speaker, a student, or faculty member — brings enormous challenges for an institution. The sheer cost of providing security for a controversial outside speaker can be daunting. At Berkeley, the university spent more than $800,000 to provide security for talks by conservatives Ben Shapiro and Milo Yiannopoulos. These incidents also can generate high volumes of negative publicity, exacerbated by the likelihood that social media will oversimplify or contort the issue at hand. So, although it may be difficult to speak about free speech, it is essential that we do so — both to set the record straight and to help educate our students about the importance of the First Amendment in a democracy.

The core principles that emerged from our discussion offer a way forward, and a framework for engaging campus communities in considering the importance of the First Amendment in a democracy:

On our campuses — public and private — free speech is presumed to be protected. To be sure, there are limits on this presumption, such as actual threats and words that are clearly intended to threaten or instill direct and immediate fear. Otherwise, it's the duty of college leaders to provide for the broadest forms of discussion, debate, and expression.

Free expression can impose a cost on the members of a campus community. We must be sensitive to the fact that this cost is not shouldered equally by all members of the community. Although this is not a reason to suppress free speech, it is an important factor in shaping how campus communities should respond to the speech.

When confronted with hateful speech, campus leaders can defend the speaker's right of expression while stating firmly and unequivocally that the speaker's views are inconsistent with the values of the institution. To be sure, this is an option that should be exercised cautiously and infrequently. A university president should not make it practice of calling the "balls and strikes" on free expression. But there are occasions that demand it, and when they arise, presidents, deans, and campus leaders should respond forcefully.

Perhaps the most important principle that emerged is this: The obligation to challenge hateful speech does not rest exclusively with those who lead our universities. It belongs to all of us. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis taught that the antidote to bad speech is more speech. In our time, that is not merely an option. That is a moral obligation.

Nor is this limited to campuses. For a democracy to function effectively, citizens must be educated, able to separate fact from falsehood, and willing to weigh in on issues of public concern. And all of us must speak out to condemn hateful expression even when it is protected by the First Amendment.

At the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, when asked what kind of government our nation's founders had created, Benjamin Franklin famously replied: "A republic — if you can keep it." His challenge has never been more compelling.

Frederick M. Lawrence, a former president of Brandeis University, is the secretary and CEO of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and a distinguished lecturer in law at Georgetown University. flawrence@pbk.org

William K. Marimow, a former editor of the Inquirer, is vice president of strategic planning for the parent company of the Inquirer, Daily News, and Philly.com. He is a graduate of Trinity College. bmarimow@phillynews.com