Frenchman chronicled the culture and history of U.S. founding

"I could not keep my eyes from that imposing countenance," Du Ponceau writes of Washington, "grave, yet not severe; affable, without familiarity. Its predominant expression was calm dignity, through which you could trace the strong feelings of the patriot."

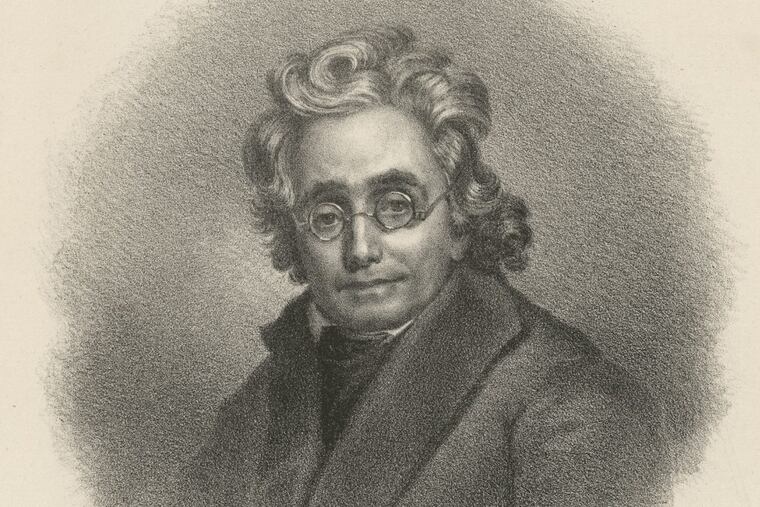

In 1836, Peter S. Du Ponceau — an accomplished Philadelphia lawyer and intellectual — wrote a series of autobiographical letters detailing his experiences as a young man during the Revolutionary War.

Du Ponceau recollects everyday occurrences that, at face value, had little to do with the conflict. One anecdote describes two men drinking at an inn. A Virginian nags his French acquaintance regarding one of France's "horrid" traditions: men kissing one another in salutation.

"The Frenchman made no answer," Du Ponceau writes, "but as it was late, he took his candle, and went up to bed." Shortly thereafter, the Virginian joined the Frenchman on his cot.

Du Ponceau's letter continues: "'Stop, Sir,' said the Frenchman, 'that wont do; I shall kiss you as much as you please, but by Jupiter! I'll not sleep with you.' "

In this passage, Du Ponceau — a French native himself — uses a comical culture-clash scenario to illustrate a quality that made his adopted country, then fighting for its very existence, a worthy cause: principles and political values mattered more than adherence to a single set of national customs.

An esteemed ethnographer, linguist, and legal expert, Du Ponceau left an indelible impact on a number of influential American institutions during the United States' formative years.

He was born on June 3, 1760, on an island off the coast of France. As he came of age, he began studying under Benedictine monks. His mother had designs for him to enter the priesthood.

Ostracized by his classmates for his intellect, Du Ponceau developed an extraordinary aptitude for foreign languages. He skipped out on his seminary studies, fleeing to Paris, where he met Baron von Steuben, the acclaimed Prussian general who had been commissioned to professionalize the Continental Army.

Von Steuben took Du Ponceau on as his secretary, and the two traveled to America in 1777 to join the war effort. The situation seemed bleak. "The enemy were in possession of our capital city; the army … were hungry, naked, and destitute of everything," Du Ponceau writes, "No foreign government had yet acknowledged our independence; everything around us was dark and gloomy."

Despite the long odds, they dived headfirst into their duties. Von Steuben spoke poor English, and it was Du Ponceau who made the general's impressive military acumen accessible to the anglophone Continental Army.

Du Ponceau regularly accompanied von Steuben to dinners with George Washington, rubbing shoulders with Alexander Hamilton and James Monroe, both of whom he befriended.

"I could not keep my eyes from that imposing countenance," Du Ponceau writes of Washington, "grave, yet not severe; affable, without familiarity. Its predominant expression was calm dignity, through which you could trace the strong feelings of the patriot."

Diagnosed with consumption in 1779, Du Ponceau repaired to Philadelphia, where his friends and colleagues feared he would die. Instead, he recovered, set up shop in Philly, and became a distinguished lawyer who practiced in the halls of the Supreme Court.

In 1791, the American Philosophical Society elected Du Ponceau its secretary. His fascination with American Indian languages influenced the scholastic priorities of the society, which became a primary research hub documenting indigenous languages and syntactic structures during his tenure. In an era when historical and intellectual endeavors centered on the cultural heritage and concerns of the Anglo-Saxon elite, this was no small feat.

He became president of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1837 and held that position until his death in 1844.

"Zeal is all I have to offer you," Du Ponceau told society members in his inaugural address. "Your choice has shown that you know how to appreciate it, since I cannot find elsewhere the motive of your preference."

Du Ponceau certainly possessed a zeal, one well-suited to the unpredictable, tumultuous — yet optimistic — social and intellectual climate that precipitated the founding of the United States.

Patrick Glennon is a communications officer at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pglennon@hsp.org