Lessons from Elvis on inspiring today's young people

When the students entered Audubon and saw his pictures on the wall, he became a peer. He wasn't a caricature. He was a 21-year-old kid who was trying to be cool, trying to go against societal norms, and trying to make a difference.

A few weeks ago, while I was out of town, my wife Johnnie offered to take our two children, Ella and Nate, to Graceland as an outing for the day We live in Memphis, but our kids have never been to Graceland and we go only when folks from out of town visit — not going to Graceland is a weird rite of passage for many Memphians.

My kids said no, though, because they worried it would make me sad if they went without me because "Daddy loves Elvis so much."

This struck me.

As a trained jazz musician and musicologist of the 16th century, my musical world always felt far removed from Elvis. Sure, I understood his cultural impact — and appropriation — and have fond memories of my parents pining over his gospel recordings, but I was a serious musician.

"Daddy loves Elvis so much."

My academic career steered me toward an administrative job with the Mike Curb Institute at Rhodes College, which included overseeing the house in East Memphis that Elvis bought from the proceeds from "Heartbreak Hotel" (his first RCA hit). He lived there while he made his groundbreaking appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, recorded "Don't Be Cruel" and "Hound Dog," made his first movie, and jammed in the studio with "the Million Dollar Quartet" (joining Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash). As one of my students, Alice Fugate, puts it, it is "where Elvis became Elvis."

The Presleys lived in the house for 13 months before life on Audubon Drive became unsustainable and they moved to Graceland. Not only did Elvis' fame cause unending disruption on the street, but the class differences between the Presleys, a working-class family from Tupelo, Miss., and the neighbors, most of whom came from prominent Memphis families, made it hard for them to find common ground.

Elvis in 1956 also represented the very thing that terrified parents the most but that made kids want to get up and change the world.

I initially struggled for a way to incorporate this house into the mission of my college and our students' experiences, as well as my personal career. It was a cool space and had an amazing vibe, but my students and I were busy diving into the jazz and hip-hop traditions of the city and looking under rocks for the untold Memphis music stories. Elvis was too obvious — everybody knows Elvis.

So there I was — an administrator who loves Elvis. Twenty-year-old me would be horrified.

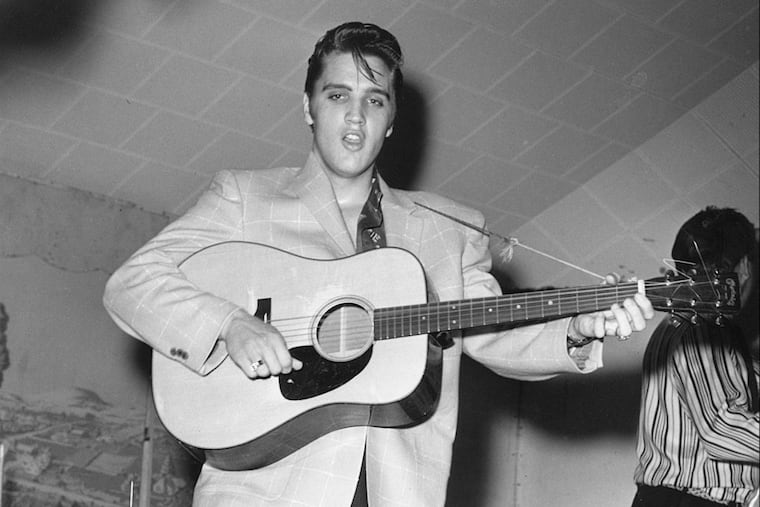

Then I started taking students to the space. Elvis died the year I was born, so he is far removed from my life, not to mention the millennials who are in college today. He has also become more legend than human, and the image that seems to pop up in most people's minds is not 1956 Elvis, but rather the jumpsuit-wearing Elvis who was fighting demons later in his life.

But when these 18-to-21-year-old students entered Audubon and saw his pictures on the wall, he became a peer. He wasn't a caricature anymore, he was a 21-year-old kid who was trying to be cool, trying to go against societal norms, and trying to make a difference. This is somebody college students could identify with, and it reminded me of the business we are in as educators — to inspire young people to be smart, cool, empathetic, and want to change the world.

Once the themes of youth and vibrancy emerged, everything made sense — Audubon was not a space to petrify a moment in time, but to preserve that moment and capture that same spirit today. Over the last five years, students have been using the space to conduct research, explore creative projects, and even produce an original house concert series with community partners in which national and local artists perform and reflect on the cultural importance of the city of Memphis.

A fire in April caused major interior damage to the property. The Mike Curb Family Foundation is supporting its restoration, but things are on hold and it is a blow.

This pause has given me a moment to reflect and listen. I read comments from Elvis fans around the world. I talk to his neighbors and people who knew him. I listen to current neighbors about how that house impacts their homes and lives. I listen to what our students think about Elvis and to what their dreams are.

People ask me what needs to happen for jazz to become culturally relevant or popular again. I don't have a great answer — there is so much wonderful music being made today, and information is flying around us so fast I'm not sure where to even begin.

And yet, I can't help thinking about Elvis. For everything he accomplished and represents, the most remarkable thing to me is how he reaches through the noise, grabs people, and doesn't let go.

Tens of thousands of people will come to Memphis this week to commemorate the anniversary of his death on Aug. 16, and it will be a deep and profound experience for many. Elvis still drives tourism in Memphis 40 years after his death and is still inspiring young college students to explore their creativity and strive to make a difference.

After all, it is young people who call us out, who refuse the ridiculousness of the past, and who take the risks we should all be taking. Now more than ever, this spirit is crucial, and we could learn something from Elvis.

Kids see things, and my kids saw something in me I didn't realize until they told me: "Daddy loves Elvis so much."

John Bass is director of the Mike Curb Institute for Music at Rhodes College in Memphis. bassj@rhodes.edu