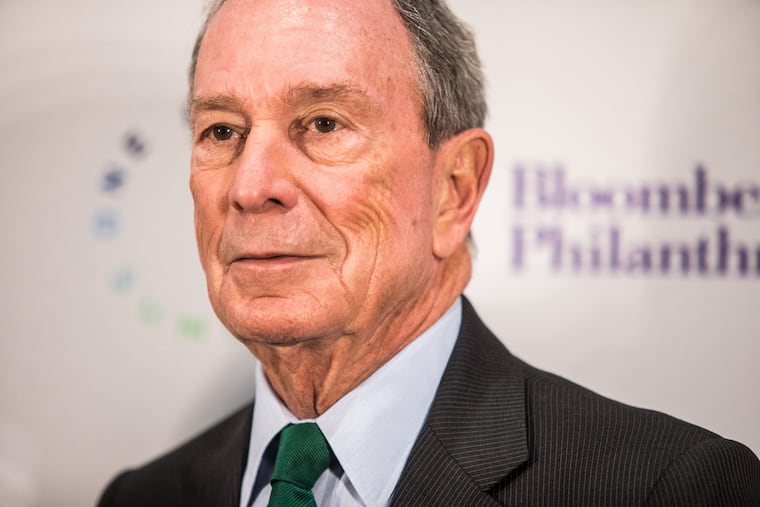

How donors can do better than Michael Bloomberg’s $1.8 billion for college tuition | Opinion

Bloomberg's investment may do the most good if it is seen as a challenge to other philanthropists to help students teetering over whether to even try to go to college at all.

Michael Bloomberg's gift of $1.8 billion in financial aid to Johns Hopkins University demonstrates his keen insight and confidence that students of modest means can compete academically with wealthy peers.

Indeed, students capable of gaining admission to such an elite college would likely succeed at Hopkins or elsewhere even without Bloomberg's help, albeit with burdensome loans after graduation.

This is not to diminish the importance of Mr. Bloomberg's remarkable act of generosity or the need for philanthropy to buttress higher education. Right now, the new economics of college mean that family wealth trumps talent: To wit, strong-performing high school students from the poorest families are less likely to earn a college degree than are relatively weak students from the wealthiest families.

Mr. Bloomberg's investment may do the most good if it is viewed as a challenge to other philanthropists to help boost the prospects of the vast majority of today's students – those who are not destined for prestigious schools, but rather are teetering over whether to even try to go to college at all.

Those philanthropists could consider the approach and lessons learned by a college scholarship and mentoring program called Give Something Back. When Give Back was founded in Illinois in 2003, the program awarded scholarships to the highest-achieving students who applied, as long as they were Pell Grant-eligible.

These Give Back students were stars, and they were scooped up by some very fancy schools, including Harvard, where enormous endowments keep the financial-aid coffers flush. But it soon became apparent that the students being chosen as Give Back scholars, while grateful for the help, were not the students most in need of that help.

To ensure that its dollars did the most good, Give Back adjusted its focus from valedictorians to those in the struggling masses. The program now makes a special outreach to groups least likely to earn a college degree, such as foster children and those who have experienced homelessness or the incarceration of a parent. Moreover, Give Back partners with colleges demonstrably accustomed and committed to educating working-class and first-generation students — places such as California State University-San Bernardino, Rowan University, Lewis University, Illinois State University, Montclair State University, and Queens College.

It's not enough to simply donate to a private endowment. As Mr. Bloomberg knows, accountability matters for ensuring the desired outcomes. In written contracts, each of Give Back's college partners agrees to reserve a specified number of admission spots, with no cost to students for tuition, room and board, or fees over four years, in exchange for a large up-front payment from Give Back, usually $1 million. Thus far, Give Back has invested in scholarships for more than 1,500 students in seven states. Perhaps as important, it has buttressed the financial aid at public colleges and universities during a time of state disinvestment.

Give Back typically selects students in the ninth grade. These students are assigned mentors who keep close track of their school and home lives. The students are expected to take college preparatory courses, to keep up their grades, and demonstrate good character. They are good, smart, hardworking young people who needed a break.

And they are urged to someday "give back" themselves, whether in time or money. Astonishingly, more than 90 percent of the Give Back scholars who have started college graduate in four years, and many have become mentors themselves to young students. As they become alumni, these students will be far more likely to also invest in the sorts of students and colleges Give Back now favors — helping to reduce inequality over time.

As Mr. Bloomberg has demonstrated, billionaires can make an enormous difference. Give Something Back's founder, Robert Carr, may not be as wealthy as Bloomberg, but his $50 million investment is undoubtedly transformative.

Let's hope others in the 1 percent – whose children are 77 times more likely to attend an Ivy League school than are students who are eligible for a Pell Grant – will follow his lead. There is no shortage of opportunities to help, with hundreds and hundreds of colleges in America, some famously prestigious, and many others that are solid, down-to-earth, and respected. All of them can change students' lives.

Sara Goldrick-Rab is founding director of the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice and author of "Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream."