Why Philadelphians should be carrying naloxone right now | Opinion

Carrying naloxone is something you too can do right now to save lives.

For many people in our community, the threat of drug overdose is a haunting daily concern. One-third of Americans are touched in some way by the opioid epidemic, with opioid use disorder affecting friends, loved ones, coworkers, or others in their community. And even if opioids have not yet hit close to home, Philadelphia has one of the highest overdose death rates among U.S. cities – with over 1,200 deaths last year – so there's a good chance residents could witness an overdose.

Few public and community spaces are immune. In just the past month, each of us has encountered a potential overdose during the course of our normal routines.

>> READ MORE: International Overdose Awareness Day: Where is Philly's overdose prevention site? | Opinion

First, at a Graduate Hospital coffee shop, a harried-looking patron raced into the bathroom and then did not emerge, generating anxiety about a possible overdose. Then, on a summer afternoon near Rittenhouse Square, a second member of our team and her son came upon a nurse in scrubs, naloxone in hand, tending to a man who had collapsed on the sidewalk. Shortly thereafter, a third member of our group emerged from her home in South Philadelphia and saw a man collapsed on her neighbor's steps whom she and a bystander helped to get emergency aid.

It is virtually impossible to control whether we witness an overdose, but we can control how we respond. Learning to recognize and treat an overdose is something anyone can do right now. The opioid antidote, naloxone (often known by its brand name, Narcan), can reverse most overdoses within minutes. Any Pennsylvanian can get naloxone from a pharmacy without an individual prescription under the standing order from Pennsylvania's health secretary, Dr. Rachel Levine.

>> READ MORE: College campuses distribute condoms. Why not Narcan? | Opinion

Why carry naloxone? With average 911 response times of seven minutes nationally, the difference between the quick receipt of naloxone from a bystander and waiting for first responders could mean the difference between life and death. And this has a profound impact at the community level. Compelling data from Massachusetts show communities with naloxone distribution and education programs had lower overdose death rates.

It's understandable to be overwhelmed by the overdose crisis or to worry about what would happen if you encountered an overdose. Many people feel this way, which is why our teams at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, the Penn Center for Public Health Initiatives, and the Free Library of Philadelphia have joined with other local groups to provide free naloxone trainings for community members. We are a group of clinicians, public health practitioners, and researchers committed to engaging the community in the face of this profound public health crisis.

Our trainings are held in public libraries, whose doors are open to everyone. No ID required, no formal sign-ups, no need to explain why you decided to come. Walk through the door, listen, and learn.

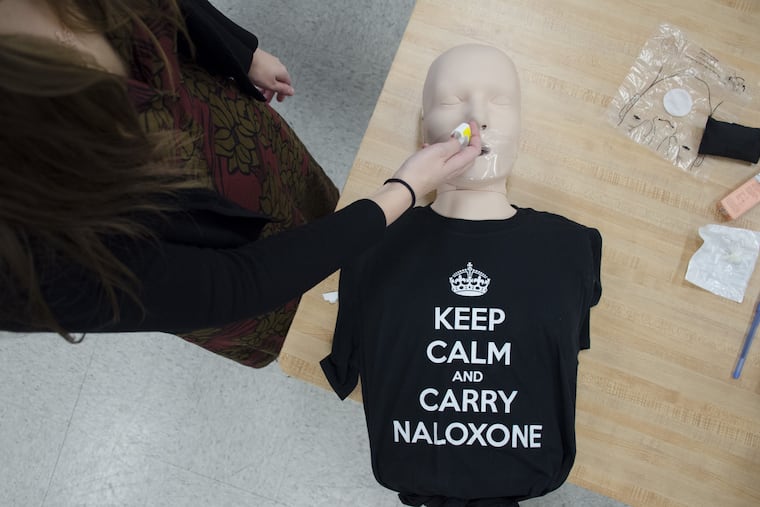

At a typical training, you will learn to recognize an overdose, how to administer naloxone, and what to do afterward. You will learn that giving naloxone is simple – the drug is a nasal spray similar to over-the-counter allergy medicine. You will learn the importance of rescue breathing because opioids suppress the body's normal reflex to breathe. You will learn that you cannot get in legal trouble by assisting in an overdose situation, nor can you hurt someone by giving naloxone. Finally, you will learn how to get naloxone and that while insurance copays vary — from $0 to over $100 — there are places in the community to access naloxone affordably.

>> READ MORE: 'Not one pill more': Taming the opioid epidemic one medicine cabinet at a time | Perspective

Most important, trainings are a safe space to connect with people concerned about the opioid crisis. You'll be able to talk through a range of challenges, hear advice from people who have reversed overdoses, and share your fears. How can I read a situation and know how to help? How can I summon the courage to intervene? And you'll be able to decide whether or not you're ready to act if someone you know, or even a stranger, needs your help. Finally, you can decide if you need another "dose" of training, and the door will be open to you again.

Naloxone alone will not solve the overdose crisis. However, naloxone keeps people alive in order to get them into treatment. Participants have told us that attending trainings gave them the confidence to get naloxone, recognize an overdose, and ultimately save the life of a fellow community member. Carrying naloxone is something you too can do right now to save lives.

To find out more about naloxone and trainings, visit the city's page on mental and physical health at beta.phila.gov.

Margaret Lowenstein is a physician in the National Clinician Scholars Program at Penn.

Rachel Feuerstein-Simon is researcher at the Penn Center for Public Health Initiatives (CPHI).

Carolyn Cannuscio is associate professor of family medicine and director of research at CPHI