Groundbreaking Philly science museum was not always beloved by city residents | Philly History

The building was situated next to one of the city's earliest baseball diamonds, and, purportedly, Wagner declined to return balls that landed on the Institute's property.

April 8 marks the beginning of National Library Week. Philadelphia is home to scores of historically important libraries that have served the city and the United States for more than two centuries. The Wagner Free Institute of Science — which doubles as a natural sciences museum and library — ranks among the most groundbreaking of the city's educational institutions, having essentially introduced the concept of free public adult educational programming in science.

The institute's origins trace back to the educational philosophies and scientific passions of its founder, William Wagner. A worldly Philadelphia-based merchant, Wagner traveled the globe on business errands for the wealthy banker and noted philanthropist Stephen Girard. During his journeys, he simultaneously built a sizable fortune and amassed an impressive collection of specimens and scientific samples — including fossils and minerals — from around the world.

His business career proved so lucrative that he managed to retire young. He gathered his scientific collection at his property known as Elm Grove, just outside Philadelphia, and pursued his passion for science full time. His endeavors led to a revolution in accessible education.

In the early 1850s, he leveraged his immense personal collection to present lectures and discussions open to the public, based out of Elm Grove. Holding these free events in the evening to accommodate the busy schedules of working people, Wagner sought to enrich Philadelphians' intellectual lives with the natural sciences, which were still relatively new scholarly subjects even for those lucky enough to receive a top-notch education.

The scope of his lectures outgrew his home, leading Wagner to procure larger facilities and enlist the service of six colleagues to help him cope with the public's demand for accessible science programming. By 1855, Wagner had incorporated the Wagner Free Institute of Science. Working out of a public hall, he and his cohort of volunteer educators covered topics including chemistry and paleontology, among scores of others, offering courses throughout the week.

Wagner worked toward a dedicated facility for the institute, tapping the famed architect John McArthur Jr. to accomplish the task. (McArthur would most famously design City Hall, which held the title of the world's tallest habitable building for 14 years. The institute in North Philadelphia, at 17th Street and Montgomery Avenue, remains one of McArthur's few structures still standing.)

Construction finished in 1865, and the building — which houses the institute to this day — began hosting Wagner's ambitiously wide-ranging educational services.

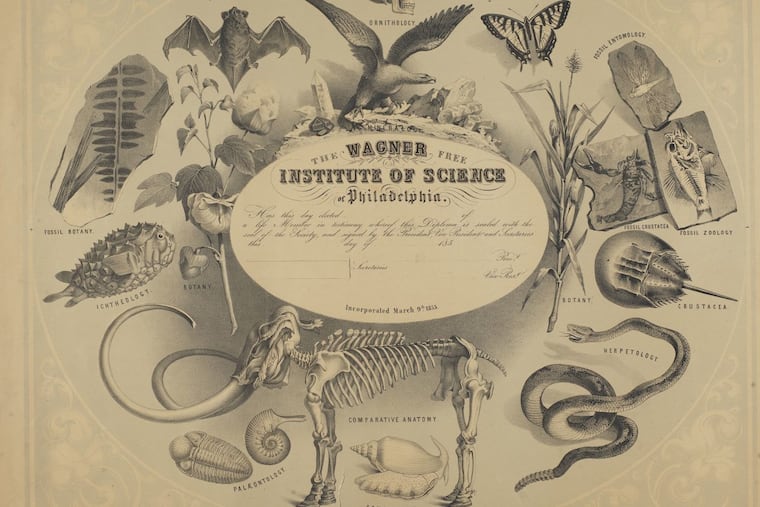

The institute was an exemplar of democratic ideals. In an era when women faced incredible hurdles accessing even basic educational opportunities, it opened its doors to Philadelphia's male and female populations alike. Providing participants with recognition for their self-driven scholarship, the institute presented diplomas, one of which HSP preserves in its collections.

(Note that not all of Philadelphia loved the institute. The building was situated next to one of the city's earliest baseball diamonds, and, purportedly, Wagner declined to return balls that landed on the institute's property).

Wagner passed away in 1885 at the age of 89, having helmed the institute from its beginning. Leadership passed to Joseph Leidy, the famed scientist, paleontologist, and University of Pennsylvania professor. Under Leidy, the institute became a hub for scientific research and enlarged its collections, the last such expansion to occur in its history.

Today, the institute — now a National Historic Landmark — stands as a rare example of a Victorian-era natural sciences museum and library and continues to offer free programming to the public.

Patrick Glennon is a communications officer at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pglennon@hsp.org