Informers everywhere

Gathering information on people in Muslim communities has become part of daily life. After 9/11, all data is considered useful. Is that how America should be?

Not long after the FBI received a tip in 2006 that two North Jersey teenagers were watching terrorist videos and muttering angrily that "Americans are their enemies" and "they all must be killed," the pair traveled to Jordan and sought to join up with insurgents fighting in Iraq.

That didn't go too well. Their help was rejected.

When the two returned home after a few weeks, one allowed the FBI to search his computer, where agents found al-Qaeda propaganda and statements of Osama bin Laden.

You'd think that would raise a cautionary flag for any would-be insurgent.

You would be wrong.

On June 5, Mohamed Mahmood Alessa, now 20, and Carlos Eduardo Almonte, now 24, were arrested as they sought to board separate flights to Egypt, the first leg in an odyssey they hoped would lead to Somalia and membership in al-Shabaab, designated by the United States as a terrorist group since 2008.

This much is alleged in a criminal complaint filed by the FBI in a New Jersey federal court at the time of the arrests. The complaint constructs a familiar story: A covert police agent befriended Alessa and Almonte last year, gathered recordings of wild talk, chronicled development of a "plan" to travel to Somalia, and helped it along where he could.

This Somalia trip, like the Iraq trip three years ago, was completely on spec, at least as described in the criminal complaint. The plotters had no contacts overseas. No specific plan on how to get from Egypt to Somalia. No weapons. No concept of what al-Shabaab might be doing - other than killing non-Muslims.

Even that was wrong. For the most part, al-Shabaab sticks to killing other Muslims.

What actually happened with Alessa and Almonte (other than a demonstration of incompetence) is difficult to say - there is little information yet available, although it is worth noting that court papers don't show much going on before the covert police agent appeared on the scene.

Nevertheless, the criminal complaint underscores two critically important issues.

First, law enforcement authorities received information directly from Almonte's family. This allowed police and federal investigators to focus their investigation on specific individuals without engulfing an entire community in a web of informants punctuated by scattershot interrogations and immigration detentions.

Second, the case should make clear that more Americans have now sought to join al-Shabaab than any other terrorist organization in the world. Indeed, the first known American suicide bomber, Shirwa Ahmed, of Minneapolis, blew himself and 29 others to bits in 2008 on behalf of al-Shabaab, which was only a minor irritant until the U.S.-backed Ethiopian invasion of Somalia two years ago.

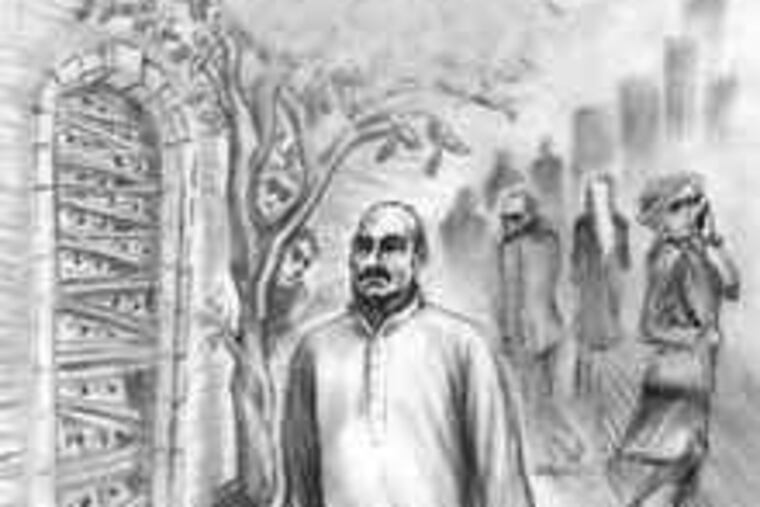

In reporting the effect of the domestic war on terror for my book, Mohamed's Ghosts: An American Story of Love and Fear in the Homeland, I repeatedly encountered Middle Eastern and South Asian communities across the country that were so intimidated by law enforcement authorities that they feared any contact with them. This anxiety metastasized over the years as it became increasingly clear to residents that thousands of informers and covert police agents were keeping tabs on the doings of community centers, mosques, bookstores, coffeehouses, and whole neighborhoods.

Informers have become so much a fact of daily life in Muslim areas that congregants joke that the FBI's informers keep bumping into the NYPD's informers leaving Friday prayer at al-Farooq mosque in Brooklyn. In Lodi, Calif., the joke is that each Muslim has his or her own personal informer. In one instance I came across, three separate informers and police agents who were scooping up tidbits at the Bay Ridge Islamic Society in Brooklyn on a single day. One of those undercover agents described himself as "a walking camera," capturing and passing along all the Kodak moments of daily life.

What is wrong with this picture?

Informers and covert agents gather names, and names go into databases. Information related to immigration goes to immigration authorities. It is passed on to revenue officials, local police, and the local Joint Terrorism Task Force. In the wake of 9/11, all information is considered useful, and it is not unusual for people to find themselves flagged in some way and, in turn, pressured to become informers. Sometimes people succumbed to the lure of steady pay for information. With payment comes the obligation to report something "useful."

Informers are a necessary tool for law enforcement officials, without question, but they carry high risks, as any agent or police officer well knows. And when informers are turned loose on a community - not on a gang or group suspected of specific criminal activity - the dangers multiply. Rumors and gossip become fact; neighbors begin to fear neighbors; residents fear authorities; the foundations of community - and hence society itself - begin to weaken. Religious institutions become tainted. Families are broken.

This is not rhetorical. The Pakistani community along South Seventh Street in Philadelphia no longer exists. Residents have scattered, fleeing like internal refugees in the face of law enforcement and immigration scrutiny. The same thing happened along Coney Island Avenue in Brooklyn. Many have gone to less prominent suburban and rural areas; others are in Canada or back overseas.

In a totalitarian society, like the old Soviet Union, such matters are immaterial to authorities. America is different, or should be. For law enforcement officials charged with preventing violent acts of terror before they become realities, it is absolutely essential to have community trust and the attendant flow of information. For democracy to have any meaning there must be an open and functioning public sphere.

This is simple common sense, as a recent study from the Rand Corp., a federally subsidized think tank, makes clear. "On occasion, relatives and friends have intervened" in cases of radicalization, the report notes. "But will they trust the authorities enough to notify them when persuasion does not work?"

In the case of Almonte, his family discussed their worries with agents, according to the criminal complaint. But Almonte, a naturalized U.S. citizen, is a Muslim convert born in the Dominican Republic. His immediate community has nothing to do with the ethnic Muslim communities from the Middle East and South Asia that have often felt besieged in the wake of 9/11. Alessa is a first-generation Palestinian American. How his family responded to police overtures, if there were any, remains unclear.

Yet as hunkered down as Muslim communities might feel, their residents have demonstrated over and over again that they are as responsible and as engaged in the public welfare of this country as anyone else. In the case of the recent botched Times Square car bomb incident, for instance, it was a Muslim vendor who first sounded the alarm about a suspicious smoking SUV on 45th Street - even though, he said, authorities would view his religious beliefs with suspicion.

In March of this year, Alessa told Almonte "that they should not include others they knew in New Jersey in their plan to travel to Somalia," according to the criminal complaint. Why? No one else they knew "was serious," Alessa said. In other words, they feared the response of other Muslim Americans.

Yet federal counterterrorism officials described the investigation as ongoing, and one told the Newark Star-Ledger that authorities hoped for "a spiderweb of arrests" soon to come.

Alioune Niass, the vendor who reported the Times Square bomb, may have said Islam is not terrorism, but in the United States these days, listening is not always a priority.