Philadelphia's Gettysburg men

From all walks of life, they held their ground during Pickett's Charge.

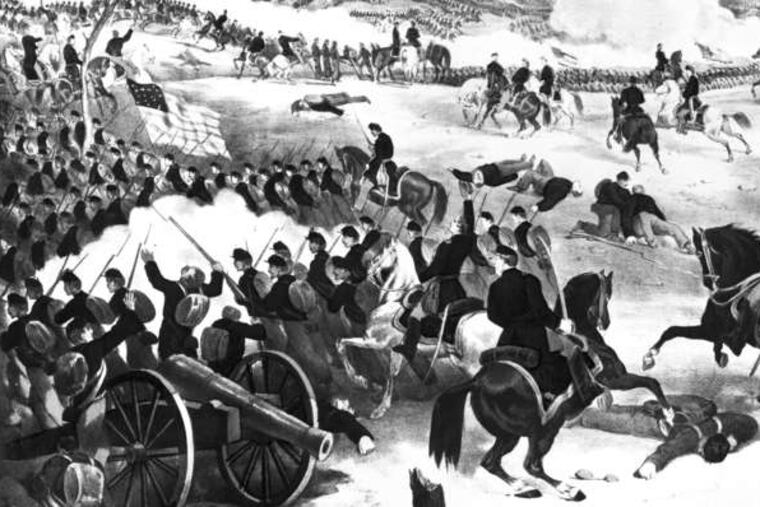

Working men from Philadelphia mustered behind a low stone wall and a copse of trees at Gettysburg 150 years ago to meet their Southern foes in the decisive engagement of the decisive battle of the American Civil War.

In civilian life the men were firefighters, clerks, printers, painters, employees of the Federal Mint, and members of many other professions. As soldiers, they joined four Pennsylvania regiments designated as the Philadelphia Brigade to fight for their country. As fate dictated during that hot, humid afternoon of July 3, 1863, the Philadelphia men held the key Union defensive position during the engagement known as Pickett's Charge.

Before the charge, the Philadelphia Brigade withstood an almost-90-minute barrage from about 140 Southern artillery pieces. One soldier wrote: "The report of gun after gun in rapid succession, smote our ears and their shells plunged down and exploded all around us. The whole Rebel line to the west was pouring out its thunder and its iron upon our devoted crest."

When the Southern guns fell silent, the members of the Philadelphia Brigade looked up to see an impressive sight: About 12,000 Confederates had formed in lines and were marching across a farm field directly at them.

Why did the outnumbered Philadelphia men hold steady through the bombardment and the advance of the larger Confederate force? For that matter, why did the Confederates follow orders to advance across the open field, devoid of natural defenses, and containing a fence that became a deadly obstacle during their charge?

As Americans and many others observe the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, they often wonder about the motivation that fueled the bravery of the soldiers on both sides of the conflict. The courage displayed at Gettysburg - during Pickett's Charge and the two days of fighting that preceded it - was common on every Civil War battlefield. A reporter for a German news agency recently asked me this very question, and he wondered why Americans were still so interested in the war.

The short answer for the second question is that we are only a few generations removed from the conflict, and many of us know of family members who took part in the historic struggle. One of my relatives fought in the wheat field at Gettysburg. We are connected to the Civil War.

As to the first question, each individual soldier had his own reason for risking his life for his country. Some strongly believed in defending the Union and the freedoms promised by the United States. Others believed in eradicating slavery. On the Confederate side, many fought for their state's right to be independent. Others wanted to perpetuate slavery. Officers and enlisted men on both sides cited God and Providence being on their side.

Certainly in the early days of the war the vast majority of the populace, North and South, were in favor of the conflict. Raising an army wasn't difficult, and recruitment often began at home. Thus, soldiers like those in the Philadelphia Brigade were fighting side by side with members of their family or hometown. Not fighting meant being branded a coward and living with that shame for the rest of one's life.

They didn't all do their duty. Both armies were plagued by desertions. Not every Southern soldier on July 3, 1863, was ready to willingly take that first step from the protective woods onto the open field and possibly face death at the hands of the Union infantry and artillery. Upon seeing the massed Confederates ready to charge, Union troops must have considered the fate that might await them. For those who might waver, officers on both sides formed "dead lines" behind their positions, a formation of soldiers who would shoot their own comrades if they ran from the fight and crossed a designated "dead line."

More often than not, though, courage was the order of the day. Of the 58 Medals of Honor awarded for valor during the Battle of Gettysburg, 30 were for service on July 3. One medal recipient was Gen. Alexander S. Webb, a proud 28-year-old West Point graduate who commanded the Philadelphia Brigade at Gettysburg. Today, Webb's likeness still holds a place of honor at the Union League on Broad Street.

What were Webb's thoughts that fateful day? An insight into his motivation can be found in a letter he wrote to his wife a day after Pickett's Charge. At one point during the fighting, when Confederate Gen. Lewis Armistead, waving his hat on his sword, led his men through an opening in Webb's line of defense, Webb just wanted a Confederate bullet to find his body.

"When they came over the fences the Army of the Potomac was nearer being whipped than it was at any time of the battle," Webb wrote his wife. "When my men fell back I almost wished to get killed. I was almost disgraced."

A Confederate victory on Northern soil that day would have placed Washington in jeopardy. European powers might have been moved to recognize the South as an independent nation.

Fortunately, Webb and other brave Union line officers quelled their personal fears, rallied their troops, and saved the nation. Webb's Medal of Honor citation put his contribution that day quite modestly: "Distinguished personal gallantry in leading his men forward at a critical period in the contest."

It fell to a fellow general and veteran of Gettysburg, Winfield Scott Hancock, to more aptly sum up the role of the Philadelphia Brigade's commander:

"In every battle and on every important field there is one spot to which every army [officer] would wish to be assigned, the spot upon which centers the fortunes of the field. There was but one such spot at Gettysburg and it fell to the lot of Gen'l Webb to have it and hold it and for holding it he must receive the credit due him."