Shippens of Phila. among families split by American Revolution

Like the Civil War, the American Revolution fractured families. The decision to support either Congress or Crown had filial - as well as political - repercussions.

Like the Civil War, the American Revolution fractured families. The decision to support either Congress or Crown had filial - as well as political - repercussions.

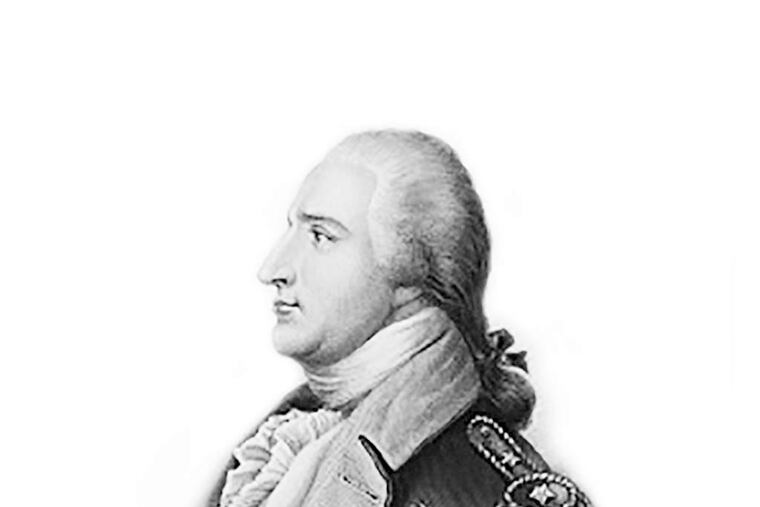

Consider Philadelphia's Shippen family, which counted among its members a delegate to the Continental Congress, as well as the conflict's most notorious caitiff: Benedict Arnold.

William Shippen (1712-1801), a self-taught physician, established a successful medical practice in Philadelphia and served with Pennsylvania Hospital from 1753 to 1778. The civic-minded Shippen helped establish Benjamin Franklin's Public Academy - which would become the University of Pennsylvania - and the First Presbyterian Church, and became vice president of the American Philosophical Society in 1768. Ten years later, he represented his home state in the Continental Congress.

Shippen's ardent support of the Revolution was not echoed by his niece, Margaret (Peggy) Shippen. Only 17 during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1778, Peggy dallied with British officers, including a dashing British spy chief, John Andre.

Following the return of the city to Patriot control, she soon met another handsome warrior, Benedict Arnold, and the two were married at Christ Church shortly thereafter.

It is believed that Peggy is responsible for introducing Arnold to Andre, between whom the plot to surrender West Point was hatched. Indeed, many historians say Arnold's attempt to support Peggy's lavish lifestyle influenced his decision to exchange the New York fort for 20,000 pounds sterling.

After the plot was exposed and Andre hanged, the Arnolds briefly stayed in British territory in New York before leaving for England. Benedict, who was in constant financial difficulty, died in 1801, leaving Peggy with sizable debts. She managed to settle them, but became very sick in 1803. Just before her death the following year, Peggy reflected upon her marriage in a letter to her father: "Matrimony is but a lottery."