A Witness to Surrender

In a letter home 150 years ago, a Union officer from Phila. wrote movingly of the Civil War's end.

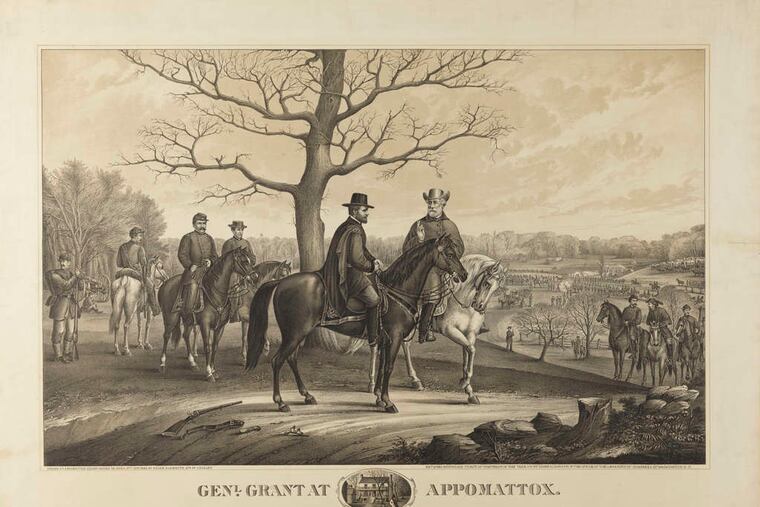

At midday April 9, 1865, Gen. Robert E. Lee accepted the terms of surrender offered by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the house of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Court House, informally ending the nation's deadliest conflict.

The surrender and its memory are preserved in many ways - scholarly histories, artistic renditions, public monuments - as well as in a letter home by one of the three Union officers tasked with delivering the terms to Lee himself.

Born in the Holmesburg neighborhood of Philadelphia, John Gibbon spent his life in the Army, serving from 1847 to 1891. He reached the rank of major general during the Civil War, and spent much of his later career in the American West. He died in 1896 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His book, Personal Recollections of the Civil War, was published in 1928.

During the war, his almost daily letters home - addressed to "Mama," i.e., his wife, Fannie, who was living in Baltimore - capture his impressions and observances of many momentous occasions. In a letter dated April 11, 1865, a wide-awake Gibbon writes to Mama in the middle of the night about the surrender, with the memory of the event still fresh in his mind:

Appomattox C.H. Va. April 11th 1865, 4 a.m.

My Dearest Mama:

I wrote you yesterday of the surrender of Lee's army, or rather my letter was written night before last, for it is now 4 o'clock in the morning, and having waked up I find it impossible to get to sleep again, and have concluded I cannot occupy the time more profitably than by writing to you an account of how things have progressed since yesterday morning.

Genls. [Charles] Griffin, [Wesley] Merritt, and myself were appointed to carry into effect the terms of the surrender. Early in the morning I rode down to the C.H. where Genl. Grant was awaiting an interview with Genl. Lee. Soon after our arrival Genl. Lee came riding up attended only by two orderlies. He looks pretty much the same as usual, but older, and his face has a very sad expression. I did not see him smile once during the interview. He has the same quiet, subdued, gentlemanly manner, for which he was always noted.

On being called up by Genl. Grant to the spot where the two sat on their horses talking, a few yards in front of where the staff officers were assembled, I shook hands with Genl. Lee and his manner was exactly the same as of old when we knew him at West Point.

All the forms of hostile armies are still kept up between us, and as yet no general communication between the forces has been permitted. As we rode along thro' the mud and rain the men flocked to the side of the road to see us, just as our men do on similar occasions. They were very quiet, made no demonstration of any kind, and rather gave me the impression that, like ourselves, they were glad it was over. They did not look, however, at all like people who were conquered and that rather pleased me than otherwise.

We then assembled in a room and went to work discussing the various details of the surrender. We were disposed to be liberal and finding them inclined the same way we formed no difficulty in agreeing upon every point that was raised, and I do not think that any six men could have had a more harmonious meeting, or settled every thing in more satisfactory manner. I will send you shortly the written argument signed by the six Genls. and bring to you when I come home the table upon which it was signed to be kept as an heirloom in the family.

We have had to supply Lee's army with rations, they being entirely without any. As for the poor horses and mules, many of them will die from the want of forage. They look terribly tired and worn down. Some of the men have had nothing to eat for three days but parched corn, and I cannot help respecting men who have fought so long and so well in support of their opinions, however wrong I may think them. The officers say very little about politics, but I think they have pretty much come to the conclusion that the Southern Confederacy has come to an end, as we all certainly do. All those of the old army when we met seem not to have changed at all, and many references were made to old and happier times.

Please to show this letter to Mr. & Mrs. L. and any other of your friends you choose and then send it to Mr. Wells, 34 So. Front St., Phila., who will return it to you after he has read it. When you will even get it I cannot tell but I dare say you will find matters of interest in it if it is stale news, for long before you get this the whole country will be ablaze with the news of Lee's surrender. Your son, J.G.