From Phila., a letter from assassin's brother

By Lynn Miller There is a Philadelphia connection to John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, that's worth noting as we mark the 150th anniversary of the assassination this week.

By Lynn Miller

There is a Philadelphia connection to John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, that's worth noting as we mark the 150th anniversary of the assassination this week.

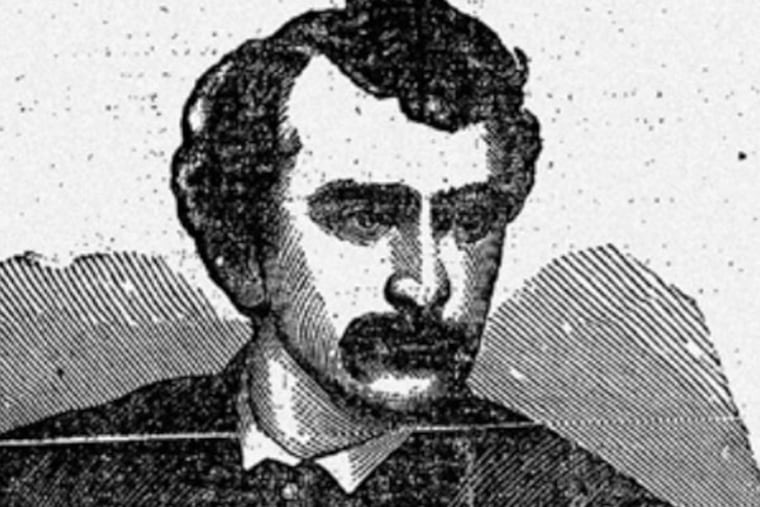

By 1865, Edwin Booth was regarded as the finest Shakespearean actor in America, the scion of a famous family of actors. John Wilkes was the 26-year-old youngest son in that family, the only one of the siblings who had been an ardent supporter of the Confederacy. For years, the two Booth brothers had feuded over their differing loyalties to North and South. Following the assassination, Edwin disowned John Wilkes and refused to allow his name to be spoken in his household.

Edwin owned Philadelphia's Walnut Street Theatre, and on that fateful day in the spring of 1865 was living on Walnut Street across from Independence Square. Three days after the assassination and before his brother had been caught and killed on a Virginia farm, Edwin wrote an agonized letter to his friend and lawyer, Eli K. Price. I found the correspondence in the Price family papers at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Its language is elliptical and opaque, expressing the conflicted thoughts of a man in anguish.

"As you have been my counsellor, personal and professional, my mind inclines to you in any case of doubt or difficulty," he begins. "You are aware that the South is my mother, endeared by the ties of birth and every coincident association which a common brute could scarcely disregard.

"The North is my wife, commanding ties and associations even more endearing. If there be any one man more interested than another in preventing any hostile separation or animosities - or could be more favorable to a cordial reunion of the relations which should subsist between them I am that man - Every impulse of my heart rises up against any act of violence or defiance of the law. ...

"My doubt is as to the good taste or propriety of any outward prominent manifestations in connection with this mournful emergency by one thus situated. My desire is to do right and 'fear not those who can only kill the body.' ...

"My visitations and associations must to some extent be renewed - I desire to avoid the possible exhibition of insincerity any where or in any respect. The insincerity in these manifestations ought to consist in a concession apparently to a timidity I do not feel - I know you will appreciate the confidence and propriety of all these presentations for your counsel and your kindness.

"My arrangements for a mission of mercy South have been all delayed by these considerations.

Very truly,

E.T. Booth"

Price clearly knew Booth well enough to understand his veiled references. His immediate response was clear and strong:

"I have your letter of this date, asking my advice. I know well your feelings and motives, and that they are good. The door is now open, as I suppose, for you to go to Richmond. You cannot but do good; and can do no harm. You will see there your former acquaintances, and may be able to do much to conciliate, and restore our torn and bleeding country to peace and Union. There is more occasion than ever for all kindly offices. The South has lost its best friend, and the most willing and able to restore peace and union, in the mad and wicked assassination of Mr. Lincoln. Consider yourself in the hands of God to do all the good you can find to do; remembering to warn the South that this last awful event, more thoroughly than war, unites the north. If there be no submission now the retribution will be stern and terrible.

I am, your friend,

Eli K. Price"

Edwin Booth's trip south may have brought him comfort as he spoke with friends and relatives there. He remained so distraught, however, that he retired from the stage for nearly a year. Eventually, he was again acclaimed in the theatre, and found that the public did not hold him responsible for his brother's crime.

Price was a leading citizen of Philadelphia responsible for shaping the borders of the city and Fairmount Park.

As a state senator, Price had led the effort to bring about the 1854 Act of Consolidation, which made the City of Philadelphia coterminous with Philadelphia County, extending the city's boundaries from two to 129 square miles, where they remain today. Philadelphia's population thus nearly quintupled to more than half a million citizens by the time of the Civil War.

In 1867, Price was appointed to the newly created Fairmount Park Commission. There he would be largely responsible for adding nearly 3,000 acres to the tiny park that had been created more than half a century earlier at the Water Works. His second great legacy to Philadelphia is the Fairmount Park that we know today.