Ship drew U.S. into World War I

The cables had started to stream in during the early afternoon. A passenger ship crossing the Atlantic sank with the loss of 1,200 lives - including 128 Americans. Chaos had erupted on board as the ocean steamer began to list. Prominent captains of industry and working-class folks alike perished in the chilly water.

The cables had started to stream in during the early afternoon. A passenger ship crossing the Atlantic sank with the loss of 1,200 lives - including 128 Americans. Chaos had erupted on board as the ocean steamer began to list. Prominent captains of industry and working-class folks alike perished in the chilly water.

No, this isn't the Titanic. And the culprit wasn't an iceberg. It was a German torpedo.

This week marks the centenary of the sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania, sunk by a German submarine off the Old Head of Kinsale, south of Ireland, on May 7, 1915.

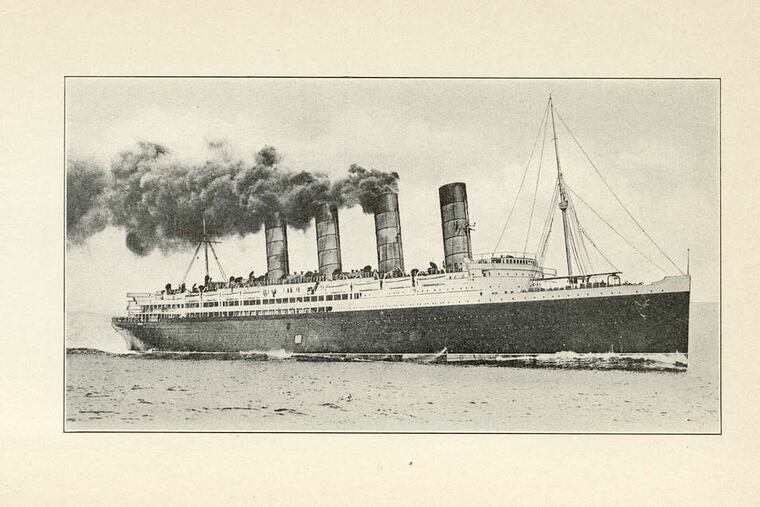

Touted as the "Fastest and Largest Steamer in Atlantic Service," the 32,000-pound Blue Ribbon winner was launched by the Cunard line in 1906. As it waited to steam from New York back to Liverpool, the Lusitania was on the verge of its 101st round-trip voyage across the Atlantic.

Twenty-one Philadelphians lost their lives in the attack, including the entire Crompton family - Paul, Gladys, and their six children. Samuel Knox, the head of the New York Shipbuilding Co. and resident of Germantown, and two other Philadelphia natives survived by clinging to debris.

In the days leading up to the voyage, the Imperial German Embassy took out ads in the shipping pages of major newspapers, including The Inquirer.

"Travelers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany . . . and Great Britain; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles . . . and that travelers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk."

Still, the attack challenged President Woodrow Wilson's policy of neutrality. At the outbreak of the First World War in Europe in 1914, a majority of Americans had supported this position. Many believed the Atlantic acted as a medieval moat, keeping at bay the irrelevant squabbles of aging empires "over there."

Germany's decision to enact a naval blockade changed this calculus. To prevent matériel from reaching its enemies, Germany let loose unterseeboots (literally "undersea boats," or U-boats) off the coasts of the British Isles, northern France, and the Netherlands.

These submarine wolfsrude (wolf packs) targeted vessels carrying supplies to Allied powers - including those with American passengers.

Three days after the attack, on a balmy May Day, Wilson was in Philadelphia. He was to give an address to 4,000 newly naturalized citizens at Carpenters' Hall. More than 15,000 people gathered to hear him speak.

The speech did not mention the Lusitania by name, but Wilson spoke to his vision of America's place in the world. His address produced the 1915 equivalent of a sound bite: the claim that the United States was "too proud to fight."

Yet Wilson mistook shifting sentiments. Though many Americans had initially supported neutrality, public opinion began to list in support of Britain and its allies after the sinking of the Lusitania. Though the United States would not enter the war for another two years, the loss of Americans aboard the ocean liner did much to stoke fears of "Kaiserism."

In July 1920, a life vest from the Lusitania, covered in seaweed and with one arm strap broken, was found floating off the end of a pier at the foot of Race Street.