Say goodbye to that crazy City Paper

The City Paper has published its final edition, joining the list of once-thriving Philadelphia newspapers, both daily and weekly, neighborhood and regional, straitlaced and far out, tabloid and broadsheet, defiantly activist and responsibly objective. Three weeks before its demise, veterans of the city's earliest alt-weekly - the Drummer - gathered at the Pen and Pencil Club for a reunion.

The City Paper has published its final edition, joining the list of once-thriving Philadelphia newspapers, both daily and weekly, neighborhood and regional, straitlaced and far out, tabloid and broadsheet, defiantly activist and responsibly objective. Three weeks before its demise, veterans of the city's earliest alt-weekly - the Drummer - gathered at the Pen and Pencil Club for a reunion.

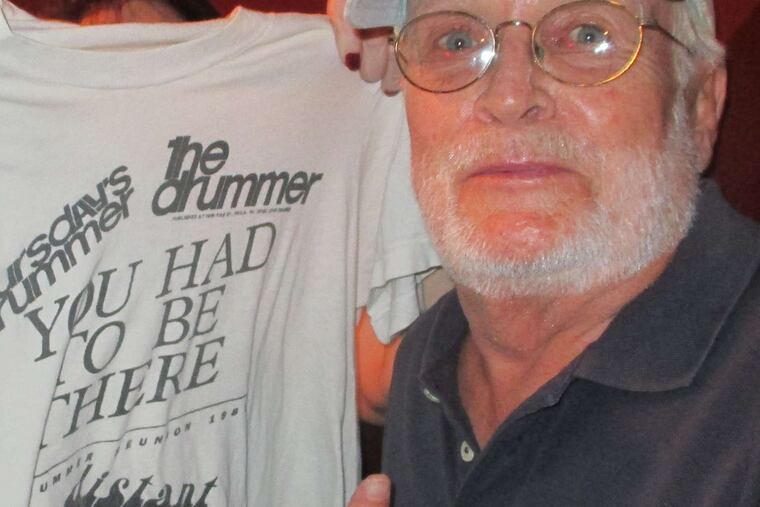

The former writers, editors, and photographers passed around a T-shirt from an earlier reunion that read "You Had To Be There." We are a paler shade of gray compared with our days as aspiring journalists in our 20s. In the early '70s, most of us were intoxicated by the possibilities and brilliance of the literary nonfiction styles pioneered by Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson, as well as the dogged, just-the-facts reporting of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

That T-shirt carried the different logos of the old paper, going back to its birth in November 1967 as an antiwar, antiestablishment "underground" biweekly called the Distant Drummer. That haunting name was born of founding editor Don DeMaio's misremembered quotation from Thoreau about civil disobedience and following the beat of a different drummer.

When the first issues appeared in coffee shops, bars, and college campuses, the gathering thunder from the war in Vietnam still seemed distant. But within weeks came the January 1968 Tet Offensive and assassinations in the streets of Saigon, and then on a motel balcony in Memphis and in a hotel kitchen in Los Angeles. Dead heroes, race riots, antidraft marches, police violence, burning flags, and the election of Richard Nixon.

Across America, underground newspapers rose up in cities large and small to cover these nation-changing events through a youthful left-wing lens.

By the time I wrote my first story for the Drummer about a Black Panther leader's speech to Temple students in the spring of 1971, the name was Thursday's Drummer. DeMaio told me the plan was to shorten the name to Thursdays. But it became the Drummer that August, and kept that name until it closed in 1979.

I wrote for the Drummer regularly during my years at Temple and even after I started reporting full time at The Inquirer, where I was covering Chester County in 1972. I wrote about the criminal trial of a rogue undercover cop. Writing under the pseudonym Kent Cassidy, I described him for Drummer readers in 1973, after he was convicted: "The best that can be said of him, all things considered, is that he never shot any nuns while in Catholic grade school."

I wasn't the only twenty-something Inky staffer writing for the Drummer in those heady days. Rod Nordland, now a celebrated foreign correspondent for the New York Times, was one of the first Inquirer reporters sent overseas on assignment. He was covering what were called "dirtball biker gang stories" in Delaware County while authoring gonzo-esque first-person columns in the Drummer under the memorable byline Ian Savage.

Why would young reporters fresh out of college and lucky enough to be hired to a staff position at a respected newspaper risk their careers by writing for a rival publication in the same city under an assumed name? Imagine doing such a thing today without informing superiors.

As the reunion T-shirt said, "You had to be there."

Bob Ingram was there. He was an editor back in the early gypsy days when the publication budget for an edition of the Drummer was $125.

The paper finally achieved some financial stability when purchased by Jonathan Stern, whose father, J. David Stern, was publisher of the city's last avowedly liberal daily newspaper, the Philadelphia Record, which folded during a strike in 1947.

"I think Jonathan fired me three times in one day," Ingram recalled. "He caught me smoking pot." Three times? I asked. "He must have," Ingram said.

Another time, Ingram had just typed the name Allen Ginsberg when the office phone rang. It was Ginsberg, the iconic beat poet, calling from New York.

"Allen, you won't believe this, but I just wrote your name and then you called," Ingram began. "Enough of that metaphysical s---," Ginsberg howled. "There were some mistakes in your two reporters' interview with me you published this week. In 50 years people reading this might think I actually said them."

The City Paper's hundreds of writers, photographers, and editors told their stories to Philadelphia for 34 years, almost three times the dozen years the Drummer was published.

Their work won't be forgotten. Not in institutional memory, and not in retrievable digital archives. And not in the lives of those they affected and those they inspired to keep telling Philadelphia's stories.

You were there, CP. You were there.

Clark DeLeon writes regularly for Currents. deleonc88@aol.com