Having failed their duty, Catholic bishops should turn over secret archives | Editorial

With the church's dismal record at the top, how can anyone trust the Catholic Church to change?

In a far-reaching special report on Sunday, journalists from the Philadelphia Inquirer and Boston Globe found that the leaders of the U.S. Catholic Church are far better at covering up child sexual abuse than stopping it.

For almost two decades, both cities have been epicenters of investigations into a sickening litany of abuse that has mushroomed across the country. The church's pattern of protecting itself over parishioners only made the scandal worse.

Following the Globe's 2002 groundbreaking report on sexual abuse in Boston, the church impaneled eight bishops to investigate the abuse and root it out. But six of those bishops were, themselves, targets of criticism for ignoring or concealing abuse in their dioceses.

They were hardly the men who should have been in charge of a new policy. And, they proved it when they exempted themselves from oversight even though it was their failure to respond to the crisis which has perpetuated it. Indeed, reporters found that 130, or a third, of the nation's bishops have been accused of failing to stop abuse. At least 15 have, themselves, been accused of actual abuse.

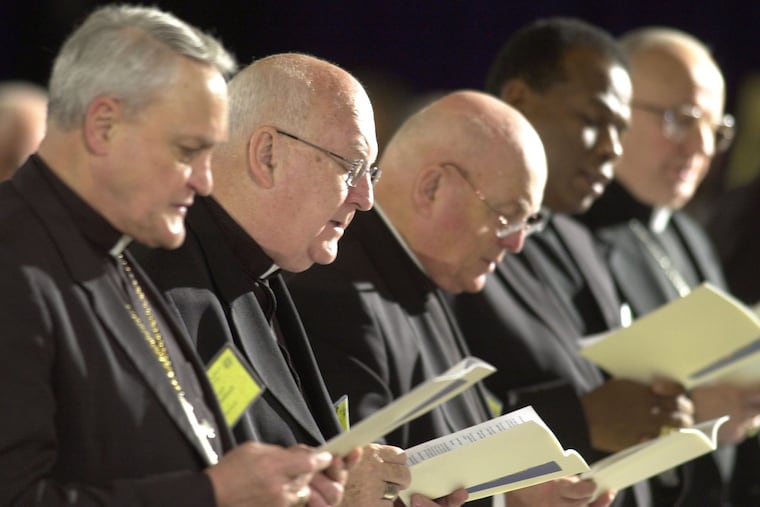

With this deeply troubling behavior at the very top of the hierarchy, how can anyone trust the church to change? There was a chance when so-called reforms were drafted during a 2002 bishops meeting, but bishops kept themselves from being held accountable. Next week, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops will meet in Baltimore — but it's hard to imagine any real progress will be made.

Because the church seems incapable of policing itself, it should turn over its secret archives to the professionals — prosecutors who understand the law and know how to adjudicate crimes.

Those records were the basis of a sweeping Aug. 14 Pennsylvania grand jury report. Without detailed accounts backed up by gut-wrenching testimony, Attorney General Josh Shapiro never would have been able to show that 301 priests abused more than 1,000 victims. Since the report's release, the attorney general has received 1,300 more complaints of clergy abuse, and Pennsylvania's investigation has sparked similar probes in more than a dozen states.

But as comprehensive as Shapiro's investigation was, only two priests were found guilty of sexually abusing children. That's because many of the incidents occurred so long ago, that the statutes of limitations have expired.

Legislators should remove the caps on statutes of limitations, and let prosecutors do their jobs. If the civil cap is removed, more information can be learned through the discovery process about how the church covered up abuse, argues child advocate Marci Hamilton, head of the Philadelphia-based Child USA. That would give a truer picture of how widespread the abuse is.

Pennsylvania was on the cusp of these important reforms until last month when Senate President Pro Tempore Joseph Scarnati (R., Jefferson) and Majority Leader Jake Corman (R., Centre) killed the legislation. The House had already passed a bill in September, and Gov. Wolf promised to sign it. Church leaders' widespread cover-up of terrible acts are unforgivable. State lawmakers who remain standing in the way of justice for victims are just as culpable.