Blackstone's warning

By Grant Calder 'It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer." Does this statement ring true to you? If so, you are probably over 40. My students, having grown up in a post-Columbine, post-9/11, post-Virginia Tech era, hesitate when I introduce them to the 1765 formulation of British jurist William Blackstone.

By Grant Calder

'It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer."

Does this statement ring true to you? If so, you are probably over 40. My students, having grown up in a post-Columbine, post-9/11, post-Virginia Tech era, hesitate when I introduce them to the 1765 formulation of British jurist William Blackstone.

It's no surprise that today's teens have a harder time accepting Blackstone's statement than I did at their age. For them, dangers to their own well-being and to the stability of the community seem to come primarily from lone gunmen and small groups of extremists. They are likely to fear dangerous people on the loose and see their government as their protector.

A half-century ago, high schoolers were instructed to assemble below ground as practice for a possible nuclear strike. I was. Now they head to the basements in preparation for a terrorist attack and are told to lock themselves in their classrooms in the case of a threat from an armed intruder.

In the 1960s and '70s, many Americans, especially younger ones, saw government as the primary menace to their personal freedom and safety. In 1970, college kids were shot at Kent State and Jackson State, not by deranged fellow students, but by National Guardsmen and police, respectively. This was also a period during which public support for the death penalty, carried out by the state, reached a historic low. Executions were temporarily halted between 1967 and 1977.

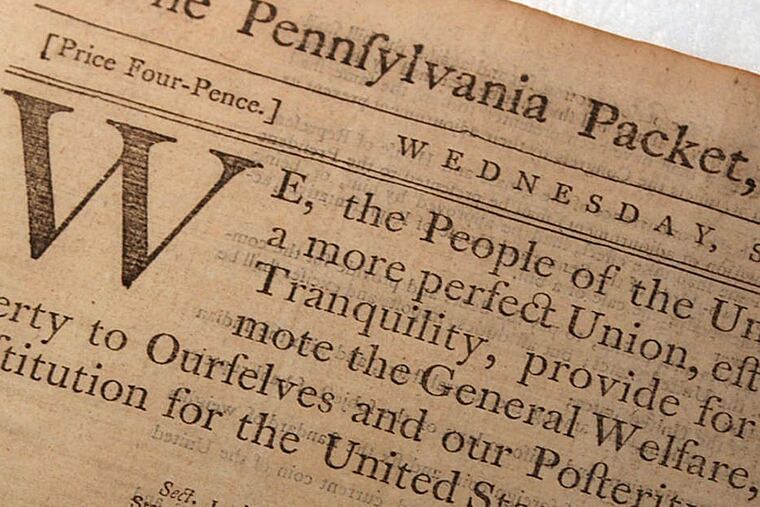

Some of the sections of the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, are already familiar to my students when we begin studying them. They know about the freedoms of speech, press, and assembly, and they are familiar with expressions such as "no double jeopardy" and "pleading the Fifth." But it doesn't immediately occur to them that these are also limitations on government power designed to prevent citizens from being silenced, or repeatedly dragged into court, or forced to confess, or imprisoned without trial, or denied the benefit of counsel. Blackstone's dictum underpins our legal system. Ben Franklin referred to it approvingly.

In weakening our devotion to this principle, advances in technology have certainly played a role. A few people can do a lot more damage in our time than they could in the 18th century - witness the attacks of Sept. 11. But technology also makes it easier to extend government power. Drones - computer-guided, unmanned aircraft - have allowed the United States to kill suspected terrorists (including at least one U.S. citizen) remotely. Earlier this year, the Justice Department secretly seized electronic phone records from the Associated Press. The National Security Agency has been collecting millions of personal e-mail contact lists.

These days we don't have much sympathy for leakers, whistle-blowers, or investigative journalists. And that's a problem, because the executive branch is notably cavalier about our constitutional rights. There is no doubt that the threats from which the NSA hopes to protect us are real, but so is the ever-present tendency toward government overreach.

Blackstone's observation remains at least as important now as it was in the 18th century. Whenever an innocent person suffers at the hands of the system we have created, we all do.