Judging the judges

It's an unfortunate irony that the corruption cases against former Philadelphia traffic judges were thwarted by the sort of legal and factual nuances that hardly troubled the defendants.

It's an unfortunate irony that the corruption cases against former Philadelphia traffic judges were thwarted by the sort of legal and factual nuances that hardly troubled the defendants.

The federal judge and jurors who heard the case clearly believed, as a state Supreme Court report and federal prosecutors contended, that fixing tickets for the connected was standard practice in Traffic Court. For the same reason, the state legislature moved with uncharacteristic alacrity and bipartisanship to dismantle the court. Even former Traffic Court Judge Thomasine Tynes' own lawyer bluntly acknowledged last week that "these guys were fixing tickets from square one."

But because of a lack of evidence that the judges directly profited from those favors, the jury found it could not convict them on the most serious federal fraud and conspiracy charges. It returned guilty verdicts only on charges of lying to grand jurors or investigators, which were leveled against four of the judges.

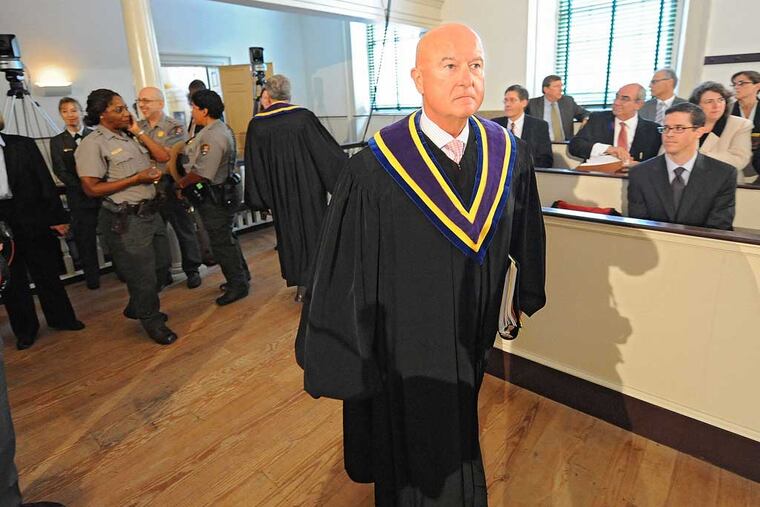

So it was that much more important that U.S. District Judge Lawrence F. Stengel chose to impose substantial penalties on the first two traffic judges sentenced last week. Tynes will serve two years in prison, and former Judge Robert Mulgrew a year and a half, for their perjury convictions. In sentencing the latter, Stengel noted, "This case is about more than one lie before the grand jury," calling it the "capstone on a . . . career marked by regular and willing participation in a pervasive system of corruption."

In treating this rampant rot with appropriate seriousness, Stengel marked a welcome departure from the chummy leniency of the state's judiciary. Last year, for example, former state Supreme Court Justice Joan Orie Melvin, who was convicted of misusing state employees and offices for political purposes, was sentenced by a state judge to serve time in her commodious house in the Pittsburgh suburbs. And in October, despite a host of questions about the conduct of another former justice, Seamus McCaffery - including his possible intervention in his wife's Traffic Court case - his fellow justices allowed him to resign without further inquiry.

In yet another act of questionable professional courtesy last month, the Supreme Court agreed to vacate its suspension without pay of Michael Sullivan, one of two traffic judges acquitted of all federal charges. While Sullivan is still suspended by order of the state Court of Judicial Discipline, the Supreme Court's ruling could clear the way for him to recover nearly two years of back pay and continue to draw his salary through the end of 2017 - when his term on the defunct court ends - for doing nothing.

Chief Justice Ronald Castille objected in a dissent that quoted Stengel, the federal judge, as noting that "the evidence was clear: the defendants were routinely granting favorable dispositions to well-connected ticket-holders." Castille also noted that judicial disciplinary officials found that Sullivan, as the administrative judge of Traffic Court, "was in a unique position to put a stop to the errant behavior."

"As far as I'm concerned," Sullivan has asserted, "I was indicted for doing my job." Now he is a step closer to being paid for not doing it.