Defend and preserve values of the marchers

By Nicolaus Mills With the 50th anniversary of Selma upon us, I asked an old friend, a retired Episcopalian minister I've known since we were both in Alabama, if he was going back to mark the occasion. He said he was not feeling up to the travel and, in a long letter, he emphasized how rarely he has spoken of Selma over the years.

By Nicolaus Mills

With the 50th anniversary of Selma upon us, I asked an old friend, a retired Episcopalian minister I've known since we were both in Alabama, if he was going back to mark the occasion. He said he was not feeling up to the travel and, in a long letter, he emphasized how rarely he has spoken of Selma over the years.

"I did not wish to use it as a credential," he wrote. "It was a gift."

His feeling is one I share, and it made me wary about returning. But I also think 50th anniversaries that honor historic events are special. They mark the last time when participants from the event will be around in meaningful numbers.

The 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, which was held in Boston on June 17, 1825, set the standard for successful commemorations early in our history. The Marquis de Lafayette, who had come to America from France as a 20-year-old military officer and fought alongside George Washington, was present, along with veterans from the battle. After helping lay the cornerstone for the Bunker Hill Monument, Lafayette and a crowd of 15,000 then listened to Daniel Webster deliver one of his greatest orations.

"Venerable men, you have come down to us from a former generation," Webster declared in his speech, in which he described the monument as a work of gratitude designed "to foster a constant regard for the principles of the Revolution." His own generation, Webster said, could best pay tribute to the patriots of Bunker Hill by the "defense and preservation" of their values.

The kind of historical commemoration that's to be avoided is the one held on July 1-4, 1913, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. That commemoration turned into an exercise in historical denial. More than 50,000 veterans from the North and South showed up, and President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner elected president since Zachary Taylor in 1848, delivered a Fourth of July speech describing the Civil War as a "quarrel forgotten," except for "the splendid valor and manly devotion of the men then arrayed against one another."

Wilson's willingness to evoke the glory of the war while ignoring its roots in slavery was in keeping with the "peace jubilee" theme of the reunion and the mood of the celebration. In the midst of the Jim Crow era, numerous black laborers worked to build the tent city for the returning veterans, but race was a taboo subject.

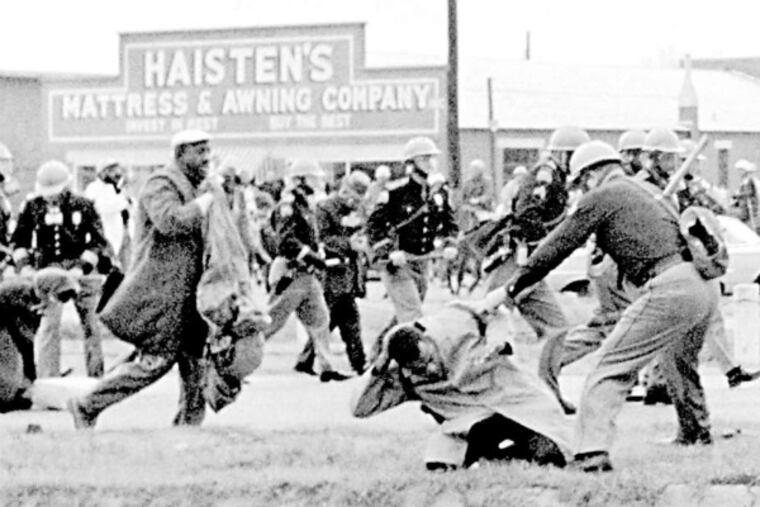

A commemoration of the Selma marches - March 7 and 9, and then the one I was on, from March 21 to 25, 1965 - has all the ingredients for being like the Bunker Hill remembrance. In U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D., Ga.), who was badly beaten in the first march - known today as "Bloody Sunday" - we have someone who can speak with authority on the meaning of Selma. He has the credentials to evoke the memory of Selma's martyrs: Jimmie Lee Jackson, a native Alabamian and young Baptist deacon, who was beaten and fatally shot by state troopers; James Reeb, a Unitarian minister from Boston, who was beaten to death by white segregationists armed with clubs; and Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit mother of five, who was murdered by Klansmen as she drove marchers back to their homes.

Among the living heroes of Selma are the many unknown black men and women who marched and then returned to the jobs and daily lives they had put in jeopardy by participating in an event that many of their fellow Alabamians, including Gov. George Wallace, looked upon with hatred. These men and women had no safe haven when the march ended, and in 1965 their sacrifices were all too often ignored by the media.

As for those of us who went to Alabama long enough to march but did not stay, we, too, filled a role. By our presence, we demonstrated that the racial injustices occurring in Selma mattered to people throughout the country. Ours was a role worth playing at a time when the civil rights movement especially needed broad support. As long as the modesty of what we did is kept in mind, I'm at ease with being part of the Selma record as well as part of a Selma reunion.

In retrospect, what's clear is that all of us were needed to make the point that still needs making: Black lives matter.