The nightmare that was Philly

(This story was originally published on April 9, 1997.)

To Jackie Robinson back in the spring of 1947, Philadelphia was far what it purports to be: ``The City of Brotherly Love. ''Before the Dodgers came to town for the first time, Herb Pennock, the Phils' general manager, telephoned his Brooklyn counterpart, Branch Rickey, and told Rickey he just could not ``bring that n----- here with the rest of your team.''

``We are just not ready for that sort of thing,'' said Pennock, the former Yankee pitching great. ``We will not be able to take the field against your Brooklyn team if that boy Robinson is in uniform.''

``Very well, Herbert,'' Rickey replied. ``And if we have to claim the game (by forfeit) 9-0, we will do just that, I assure you. ''

Whatever degradation Jackie Robinson faced during the 1947 season - and it was immense - few teams treated him as disgracefully as the Phillies. While Pennock, his players and assorted others had a hand in the despicable affair that unfolded - incluing the management of the Ben Franklin Hotel, which would not provide the Dodgers with rooms because the presence of that ``nigra'' - the chief culprit was Phillies manager Ben Chapman , long deceased but forever remembered for his hateful taunting of Robinson. Manfully - and with uncommon dignity - Robinson quietly endured the unrelenting array of insults that Chapman showered on him, even though he would later concede in his stirring autobiography, ``I Never Had It Made,'' that Chapman and his Phillies had ``brought me nearer to cracking up than I ever had been.''

``What happened...well, it was like a door that no one knew who was behind,'' said former outfielder Harry ``The Hat'' Walker, who came to the Phillies on May 3 of that season in a trade with the Cardinals and won the National League batting title. ``No one knew what to expect (when the color line was broken)...but one thing is sure, (Rickey) could not have chosen a better person to do what had to done. No one was tougher than Jackie Robinson. "

Or had to be. On May 9, the same day the Dodgers were to open their three-game series in Philadelphia, news broke out of St. Louis that the National League had averted an anti-Robinson boycott led by Cardinals outfielder Enos Alaughter. Former Phillies catcher Andy Seminick remembers that he and his teammates also held a vote whether to take the field or not. Ultimately, Seminick said, only ``a few'' of the Phillies were in favor of boycotting the Dodgers game, but it was a loud and unseemly few, led by their unspeakably crude manager.

To elucidate just how unspeakably crude Ben Chapman was, an incident that occurred while he had been an outfielder for the Yankees back in the '30s is commonly recalled: When some fans in the Bronx began jeering him one day, Chapman, born in Tennessee and raised in Alabama, turned to the crowd and called, ``(Bleeping) Jew (bleeps). '' In his first encounter with Robinson, during a three-game series in Brooklyn back in April, he taunted the rookie with the shameful fervor worthy of the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

Author Roger Kahn recounted the scene in his book, ``The Era.''

``Hey, you there,'' Chapman shouted at Robinson. ``Snowflake. Yeah, you. You heah me. When did they let you outa jungle...

``Hey, we doan need no n----- here...

``Hey, black boy. You like white (women), black boy? You like white (women)? Which one o' the white boys' wives are you (bleep) tonight? ''

No one could quite believe their ears. Former Dodger pitcher Rex Barney recalls that he and his Brooklyn teammates sat in the opposite dugout in shock. Seminick (who claimed he did not participate in the ugly spectacle that occurred) remembers, ``Emotions ran quite high. ''

Courageously, Robinson blocked it out - or tried to. Rickey had told him he would have to turn the other cheek in the face of the racial slurs he was certain to hear or else it would jeopardize the black cause for years to come. So Robinson held his tongue. But there was a part of him that wanted to lash out at Chapman and the Phillies, some of whom at one point stood in row atop the dugout pretending to shoot tommy guns at Robinson as he walked up to home plate.

Chapman and his players derided Robinson for his ``thick lips;'' told him he should go back where he belonged - the South - and take up picking cotton or swabbing latrines; and warned his teammates that they would become infected with sores if they happened to touch a towel or comb Robinson used. In his autobiography, Robinson remembered how close he came to blowing up.

``Hate poured from the Phillies dugout,'' Robinson wrote. ``...I felt tortured and I tried just to play ball and ignore the insults. But it was really getting to me. What did the Phillies want from me? What, indeed, did Mr. Rickey expect of me? I was, after all, a human being. What was I doing turning the cheek...?

``For one wild and rage-crazed minute...I thought what a glorious, cleansing thing it would be to let go. To hell with the image of the patient black freak I was supposed to create. I could throw down my bat, stride over to the Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth...

``The haters almost won that round. ''

Because of the horrific display that Chapman and the Phillies had staged in Brooklyn, great uneasiness followed the Dodgers to Philadelphia for the series at Shibe Park. Unwilling to cooperate with Pennock and leave Robinson back in Brooklyn, the Dodgers arrived and found themselves without hotel space. When the bellboys at the Ben Franklin stacked their luggage out on the sidewalk, the Dodgers trooped over to the Warwick Hotel, where the manager said he would be delighted to have them.

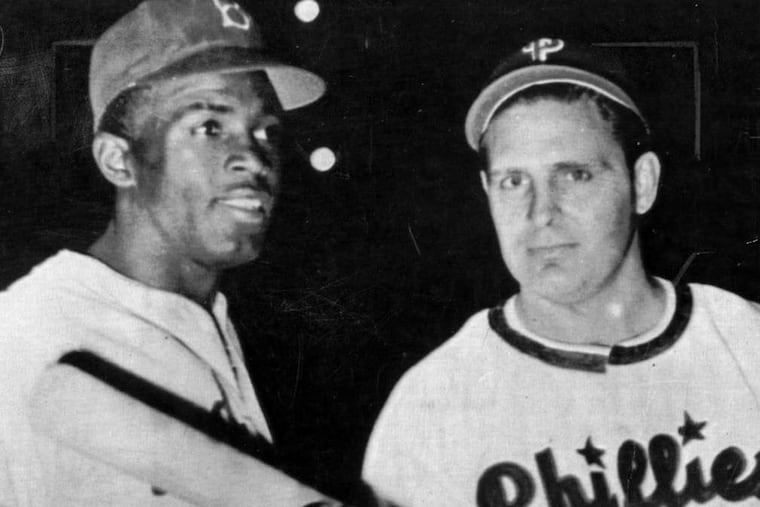

Big crowds filed into Shibe Park to see - and jeer - Robinson, who found growing support not just inside Dodger clubhouse but in the press. In fact, in the days leading up to the series, Chapman had come under sharp attack because of his behavior in Brooklyn. Sports writers such as Dan Parker of the New York Daily Mirror, characterized him as a ``guttersnipe,'' and syndicated Broadway columnist Walter Winchell promised to ``take a big hit on that bigot. '' Under the increasing scrutiny of Commissioner Happy Chandler and National League President Ford Frick - both of whom fired off warnings to the Phillies to curtail racial baiting - Chapman sat down for an interview with a reporter from a black newspapers and explained that he was not ``anti-Negro,'' that - as a piece of strategy devised to throw an opposing player off - it was common for him to call Yankee centerfielder Joe DiMaggio a ``wop'' and Cardinals third baseman Whitey Kurowski a ``Polack. '' To drive home his point that it was ``nothing personal,'' Chapman sent word to the Dodgers that he would be willing to stand with Robinson for a photograph.

Jackie agreed, but had great personal reservations.

``Mr. Rickey thought it would be gracious and generous if I posed for a picture shaking hands with Chapman,'' Robinson wrote in his autobiography. ``I had to admit, though, that having my picture taken with this man was one of the most difficult things I had to make myself do...There were times, after I had bowed to humliation like shaking hands with Chapman, when deep depression and speculation as to whether it was all worthwhile would seize me. ''

Unintentionally, what Chapman and the Phillies succeeded in doing was what Rickey had hoped: The string of unconscionable abuse that issued from their lips only solidified and united the Dodgers behind Robinson. While a handful of players in the Brooklyn clubhouse remained Robinson detractors - chief among them Bobby Bragan, Hugh Carey, Cookie Lavagetto and Dixie Walker (brother of Harry) - infielder Eddie Stanky, a Philadelphian who had signed Dixie Walker's anti-Robinson petition in spring training, became so furious at the Phillies that he told them, ``Not one of you has the guts of a louse. '' When Chapman called out to Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese, ``Hey, Pee Wee...How ya like playin' with a (bleep) n-----? '' Reese walked up to Robinson and draped an arm around the rookie's shoulder. Even traveling secretary Harold Parrott found himself in a position of defending Robinson.

Parrott remembered a conversation he had with Chapman in his book, ``The Lords of Baseball.''

``Poor Parrott,'' Chapman told him. ``Know how you're going to end up?''

``How? '' Parrott asked.

``You'll be nursemaid to a team of 24 n-----,'' Chapman said. ``And one dago. '' (Which would have been a reference to Dodgers rightfielder Carl Furillo, a Reading native who, as Parrott recalled, Chapman ``did not like, either. '')

Parrott looked Chapman in the eye and said: ``If I was short a hotel room and had the choice of bunking with you or with No. 42 (Robinson), know what I would do? I'd room with Robinson. ''

Harry Walker remembered Chapman as, well...``outspoken.''

``God himself could have come down and Ben would have been on him,'' Walker said. ``Chapman just had a way of stirring up trouble. ''

Barney concurred.

``The whole blame has to go to Chapman,'' Barney said. ``He just thought it was a terrible thing - and he said so - that a black man could be allowed in baseball.''

(This story was originally published on April 9, 1997.)