At the old Garden, Gola helped rebuild a sport

NEW YORK - On the west side of Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, where the old Madison Square Garden used to stand, is a 50-story corporate tower of glossy gray granite and concrete called One Worldwide Plaza.

NEW YORK - On the west side of Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, where the old Madison Square Garden used to stand, is a 50-story corporate tower of glossy gray granite and concrete called One Worldwide Plaza.

WebMD has leased 50,000 square feet of office space within the tower, which also serves as the U.S. headquarters for Nomura, Japan's top global investment bank. The building houses a Bally Sports Club and an Off-Broadway theater, and on opposite sides of a street-level entrance are a Starbucks and, for good measure, a Pret A Manger. The media center for Super Bowl XLVIII is five blocks away.

The ground here has changed a lot in 62 years, since Tom Gola owned it.

In and around Philadelphia, those who knew Gola, had watched him play basketball, or had tracked his career in sports and public service reacted to the news of his death Sunday at age 81 with a mixture of sadness and wistfulness, with an appreciation for his achievements and his grace. Those sentiments have been stronger, certainly, for those of us affiliated with Gola's alma mater, La Salle University. (I graduated from La Salle in 1997.) He was loyal to his school and his city, and we treasured him for that loyalty.

But Gola has an important and oft-underappreciated legacy beyond his hometown and his university, and it traces to the site of the old Garden, to a bygone era and a troubled time for college basketball.

In 1951, just as Gola was beginning his freshman season at La Salle, New York was college basketball's epicenter. A series of point-shaving scandals earlier that year involving City College of New York, Long Island University, and NYU had crushed the sport's credibility, fostering the perception that it was run by gamblers, gangsters, and thieves. Held at the Garden, the National Invitation Tournament was the crown jewel of the college basketball season at the time - more highly regarded than the NCAA tournament - and it was there that the scandals' aftershocks posed the greatest threat. There was no March Madness then, no field of 68. There was the 12-team NIT, and in March 1952, there were La Salle and Tom Gola.

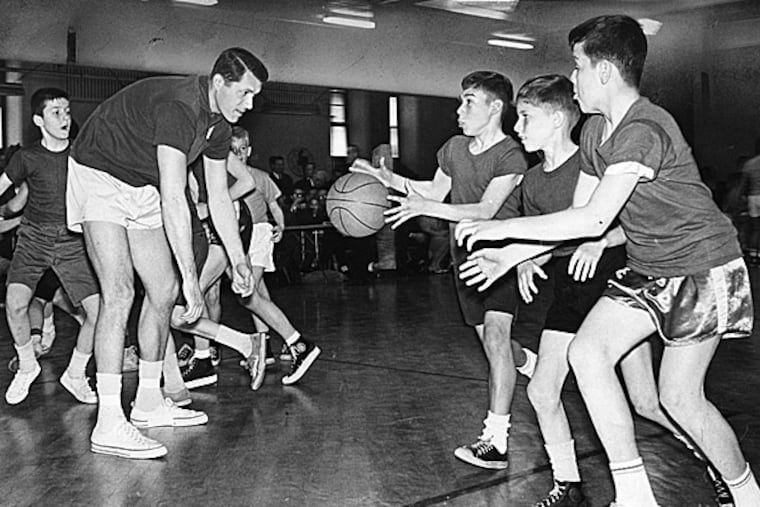

Gola averaged 17.4 points and 17.1 rebounds that season, captivating the country by playing basketball in a manner that no man his size had before him. The notion that someone 6-foot-6 could be anything other than a center was revolutionary, yet Gola had no fixed position on the floor. He was a center. He was a guard. He was a forward. He was whatever La Salle needed him to be.

"He had no flair. He was straight up, straight down, straight at you," former Temple coach John Chaney told me in 2006. "He didn't have [any] bells and whistles on him. He just played the game the way it was invented - clean. I mean, I don't think fans today could appreciate it."

When La Salle beat Dayton, 75-64, to win the NIT, Gola emerged as the tangible symbol for college basketball's rebirth - upright of character, free of scandal, the perfect athlete for the media mythmaking so common to that period. He appeared on TV with Ed Sullivan. Gola's father, Isidore, was a police officer, and a magazine profile played up the danger and blue-collar honorability of the job and its role in Gola's upbringing.

("Poppa's all right," Gola's mother reportedly told her children one night, in an anecdote that was likely apocryphal. "He hit the robber three times with five shots.")

In December 1952, Ned Irish, Madison Square Garden's president, created the Holiday Festival, an early-season tournament, to capitalize on the good feelings that Gola had cultivated there. That La Salle then won the national championship in 1954 only added to his legend.

"The guys [who] had shaved points were gone, to jail or somewhere else," Gola told the New York Times in 2002. "But it was a different world for the rest of us."

Everyone soon learned just how different college basketball's world had and would become. In Gola's senior season, La Salle advanced to the NCAA title game again but lost to Bill Russell and the University of San Francisco. When the Dons repeated as national champions in 1956, Sports Illustrated's Kellie Anderson wrote in 2006, they "shifted college basketball's balance of power from white to black, from offense to defense . . . from horizontal to vertical."

Gola was the ideal bridge for that gulf between old and new. Growing up, he had earned the respect of Philadelphia's best black players by competing against them in the city's playgrounds, schoolyards, and summer leagues, and his style of play established the template for Oscar Robertson, Magic Johnson, even LeBron James.

"He was easily one of the greatest players," Chaney said. "Without any peers, he was just something very special."

He was a transcendent figure in the sport and its history, and a piece of that history died with him Sunday. The rest of Tom Gola's legacy deserves to survive all the changes yet to come to sports and society, the unstoppable passage of time. The rest of it survives with us.

@MikeSielski