Raveling helped Villanova recruit Southern African Americans

Early in 1965, George Raveling's eye was drawn to a tiny item near the back of a Sports Illustrated. A basketball player named Johnny Jones, he read, had scored 84 points in a Florida high school game.

Early in 1965, George Raveling's eye was drawn to a tiny item near the back of a Sports Illustrated. A basketball player named Johnny Jones, he read, had scored 84 points in a Florida high school game.

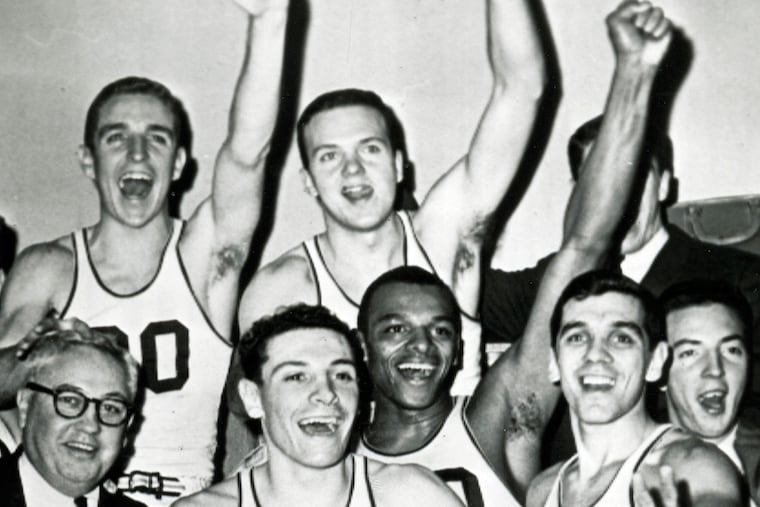

That curiosity would result in one of the most important developments in a Villanova basketball history that will be enriched at this weekend's Final Four in Houston. The 27-year-old Wildcats assistant coach's interest in Jones would create a talent pipeline from the segregated South to the Main Line - an "underground railroad," one Philadelphia columnist termed it.

"What I began to realize was that this was a virgin market," Raveling, 78, said this week. "It was like I'd discovered oil and had no competition. Nobody else was looking for oil in Florida and Alabama but me."

The recruiting bonanza not only had short-term impact - the 1971 Wildcats would reach the NCAA tournament's title game - but long-term as well. It helped them establish both an advantage they still enjoy over Big Five rivals and a welcoming reputation among the African American athletes then emerging from the Deep South and elsewhere.

And, fueled by players segregated Southern colleges wouldn't recruit and most integrated Northern programs were afraid to recruit, Villanova's success also extended its profile beyond the school's traditional Mid-Atlantic base.

"Villanova knew that it was the right time to do the right thing," said Raveling, a 1962 graduate who left in 1970 for an assistant's job at Maryland and later was the head coach at Iowa and Southern Cal.

At the moment segregation was being challenged, Raveling found Jones, who would average nearly 20 points a game for his career. Elsewhere in Florida, he discovered Howard Porter, who nearly won the Wildcats an NCAA title.

Along with other Southerners such as Alabama's Sammy Sims, they helped Villanova build a legacy, one that has resulted in four Final Four appearances - 1971, 1985, 2009, and, of course, this weekend.

"I believe it gave us an edge in recruiting that the other schools in the Big Five didn't have," Raveling said. "It was the early fabric-building of Villanova's commitment to African American athletes. Villanova benefited from having the courage and commitment to do the right thing."

Raveling got a jump

Villanova had been recruiting black players from Philadelphia and Washington, but, until Raveling expanded its reach, the other Big Five schools had had more impressive postseason resumés.

La Salle had won the 1952 NIT and the NCAA in 1954, and was an NCAA runner-up in '55. Temple had captured the 1939 NIT title and had two Final Four appearances in the 1950s. St. Joseph's had reached a Final Four in 1961.

But since Porter led Villanova to its first of four appearances, in 1971, only Penn (1979) has gotten to a Final Four. And the 1985 Wildcats, of course, won a national championship.

When Raveling played there, he was, he said, one of only 11 blacks on Villanova's campus. "And 10 of us were on athletic scholarship."

In 1963, Wildcats head coach Jack Kraft hired the Washington native as one of the college game's first black assistants and his top recruiter.

Intrigued by that 1965 item in SI's Faces in the Crowd section, Raveling called Jones' coach at Blanch Bly High in Pompano Beach. Convinced the 6-foot-5 forward's 84-point performance was no fluke, Raveling asked who else was recruiting him.

"Just the traditional black colleges - Tennessee Tech, Bethune-Cookman, Florida A&M," he said.

Raveling traveled there and asked Jones to consider Villanova.

"He said he didn't know a lot about Villanova but, if for no other reason than it was the only white school recruiting him, he'd have to think about it," Raveling said.

When Jones made a visit, he signed on the spot.

The young assistant's timing was perfect. While cracks were developing in the walls of athletic segregation, North and South, they hadn't fallen yet. So, virtually alone, Raveling mined the Deep South.

"The two states I really went hard in were Florida and Alabama, where all the high schools were still segregated," he said. "I would go to a game, and I'd be the only person there from a predominantly white college."

A year later, he uncovered Sims at segregated Carver High in Montgomery, Ala. But he netted his big catch in 1967 after a call from an Orlando sportswriter.

"I'd built up a lot of relationships down there," he said. "Sometimes guys would call me and say, 'Hey, you need to come see this kid play.' Well, this one writer said, 'George, there's a kid down here at Sarasota Booker who might be the best player in the history of this state, black, white, pink, or red. He can shoot lights out. He's 6-9, 6-10. He can run the floor, block shots, do it all.' "

It was Porter, and his coach told Raveling a familiar story. Despite his ability, only black schools seemed interested.

On that same trip, the Villanova aide scouted the National Negro High School Championships in Montgomery. There he saw a 7-2 center from Dothan, Ala., future Hall of Famer Artis Gilmore.

History of success

What kept many schools away from players such as Porter and Gilmore were worries about the academics offered by badly underfunded all-black schools, many of which didn't even offer SAT testing.

"A lot of Northern colleges internally were grappling with the whole segregation issue," Raveling said. "And I think there was a mind-set that these Southern school systems were inferior."

Both Porter and Gilmore committed to Villanova, but grades were a concern. To help, Raveling enrolled them in Philadelphia's now-defunct Brown Prep for the summer. He got them jobs and put them on the Narberth League team he coached, Three Country Boys.

"We scored 100 or more points almost every game," he said.

Also on that team was 6-10 Hal Booker from Pennsylvania state champion Darby-Colwyn in Delaware County. He wanted to go to Villanova, too, so Raveling signed him up at Brown.

But when they took an SAT equivalency test, only Porter, who would become one of Villanova's all-time greats and play seven NBA seasons, passed. Gilmore would lead Jacksonville to a Final Four, while Booker was a Division II all-American at Cheyney.

"Can you imagine? Villanova would have had a 6-9, 6-10, 7-2 front court, with two future NBA players and the Division II player of the year," said Raveling.

Those journeys south almost landed Villanova another outstanding Alabama big man. Elvin Ivory, a 6-8 center from Birmingham who would play in the American Basketball Association, had agreed to be a Wildcat.

Arranging his visit, Raveling booked Ivory on a flight from Birmingham to Philadelphia via Atlanta.

"But when he got off the plane in Atlanta, a coach from Southwest Louisiana intercepted him and took him there," said Raveling. "When he didn't show up, I called his coach. He said he knew he was on his way because he'd put him on the plane."

Thanks in part to Raveling's Southern strategy, Villanova has maintained a high-profile and remarkable level of consistency through the decades. Since 1970, it has a Big Five-best 29 NCAA appearances. In that same span, Temple has been there 27 times, Penn 22, St. Joseph's 13, and La Salle 9.

"We came in at the tail end of segregation," Raveling said. "Once schools in the South started opening up and integrating, now it was a contest. But by that time, we had built the program up.

"I tell [current Villanova coach Jay Wright] that all the time. The best thing Villanova has going for it is its long history of success with black athletes."

@philafitz