SOME TIME Thursday night, probably early, Sharrif Floyd's incessant nervous foot tapping is going to cease when NFL commissioner Roger Goodell strides to the Radio City Music Hall podium and calls his name.

Floyd will rise slowly, dressed impeccably in a tailor-made suit, maybe a little diamond bling dangling from his ear, and begin the perfunctory hugs of his inner circle. Then tears will slowly dribble down from his big, round cheeks and it will all flow back to him.

Who they are. What they did. The role they all played. How it took every one of them - and, obviously, Floyd himself - to arrive at this destination. To be a first-round NFL draft pick.

Floyd will reflect on the journey when time was measured second-to-second, minute-to-minute. When he had no dreams. When his stomach ached from hunger pangs. About a kid who trusted, when it wasn't so easy to trust. About the kid who used to shovel snow for food money. About the kid who arrived before everyone else at George Washington High School looking for breakfast, because he hadn't eaten anything the previous night.

It's about that kid, the one full of character that the ferocious, cracked-concrete streets of Northeast Philly could have easily inhaled. And didn't. It says something about Floyd, and the caring, tender circle around him.

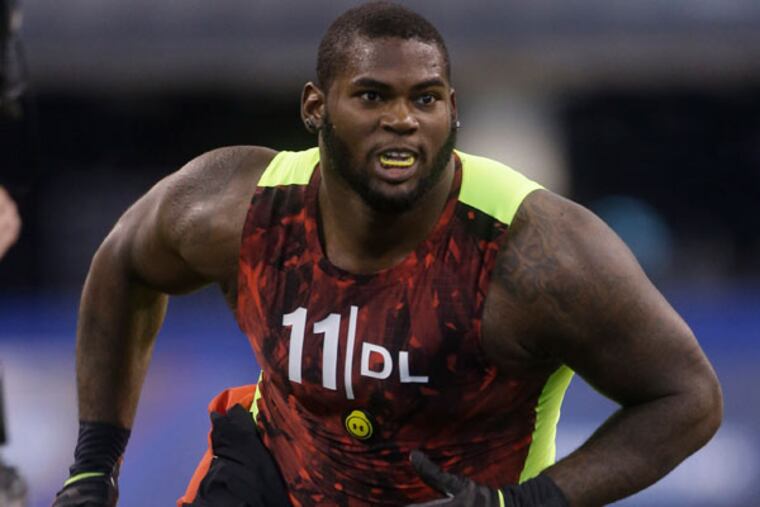

When Floyd reaches the stage and hugs Goodell, the 6-3, 300-pound Florida defensive tackle with the unending energy and drive will be the highest player from the Philadelphia Public League taken in the NFL draft since Frankford's Blair Thomas was chosen second overall in the 1990 draft by the New York Jets.

It took a myriad of people in his life, it seems, to get Floyd here. Like Washington head coach Ron Cohen, and his staff, Andre Odom, Mike Wallace and Greg Garrett. Like the guidance counselor who took him in, Dawn Reed-Seeger, and Kevin Lahn, the wealthy suburban outsider who everyone in Floyd's inner mix initially wondered about, but who eventually gained their trust, and who in the end wound up adopting him.

And then there is "Ma," as Sharrif calls her, Lucille Ryans, his grandmother who took him in. Not only him, but her children's children, and her children's children's children. She managed to raise him, instill in him a sense of right and wrong, while stuffed into a cramped, dilapidated home with cracks in the ceilings and walls, and strangers constantly shuffling in and out.

It was Ma who used to take Sharrif every Sunday to a small house converted into a Baptist church.

It all went into a product Floyd maintains is still forming.

"It's been a long road, and a long way from growing up and what I've been through and where I am today, and I think it all goes way back to one basic thing: Are you going to do the right thing?" Floyd said. "Coach Cohen used to drill in me, 'Are you going to do the right thing when no one is looking? When no one really cares what's going on, what are you doing? Will you hold yourself accountable?' I wanted to do the right things. That's what pushed me.

"The seed came from Grandma, for starters, who I lived with when I was young, then it grew to the people that came into my life. Once I was out on my own around 16, it was me growing up much faster than I had to and understanding what was right and what was wrong. It's all about never following the crowd and being your own leader. I still have some of those nights when I do go back to those times."

The circle

Washington coach Ron Cohen is like the Yoda of area high school football coaches. He's the type you find sitting at the mountain top dispensing the sage wisdom, "Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering."

Cohen also sensed something special about Floyd early. He was large. He had good feet, and an indomitable will. Floyd always seemed to carry a bigger-picture aura around him - that he was destined to go somewhere in life. Cohen quickly noticed another unique quality: Floyd was willing to listen.

But Floyd was from an unstable home. His mother was constantly shadowed by street demons and the man he thought was his father wasn't. He never knew his biological father, who was shot and killed before Sharrif was born. After Sharrif had surgery to repair the torn ACL in his left knee his sophomore year, he got off a bus and was crutching the eight blocks home when the man Floyd thought was his father drove by and beeped the horn, according to Wallace.

That turbulent young life stirred a deep rage. The situation grew so unbearable that Floyd moved out and was on his own his junior year, living a sort of nomadic existence, periodically bouncing from home to home, before eventually staying in the furnished basement of a friend his senior year.

"That's the kind of home life Sharrif dealt with, so I wanted to surround him with good people that are still with him today - it takes a village to raise a child - but not just Sharrif, these people took in a lot of other kids, too," Cohen said.

So Cohen entrusted Floyd with Odom, a self-made Washington alum who bounced around during his youth in the Philadelphia foster-care system. Odom, whose biological parents were drug addicts, overcame great obstacles to achieve everything he has today.

"I came from the same neighborhood as Sharrif, and coming from where we come from, a lot of guys are forced to grow up young," said Odom, a Temple graduate who served as an Owls assistant coach under Steve Addazio and will soon work in the Chicago Bears' scouting department. "I was impressed by the way Sharrif carried himself. He had such confidence, but he had a hard time trusting people at first. But my background was worse than his. We were able to kick it off immediately. Coach Cohen helped save my life, and this was something I wanted to do not just for coach Cohen but for other kids.

"Everyone tried recruiting that kid. I mean drug dealers, everyone and their mom tried to get close to Sharrif. No one really cares unless you have something to offer. Me, Mike Wallace and Greg Garrett, we didn't have any ulterior motives. I wanted to give back, and it's the same way Greg and Mike are. Through time, Sharrif began opening up to other people. Sharrif had a gift from Day 1. He was able to show happiness and joy about playing football. There was anger there over his circumstances. But Sharrif had an ability to not let the anger overtake him."

Wallace and Garrett both go back to the time Floyd went house-to-house, trudging in knee-deep snow, asking if he could shovel driveways and sidewalks, motivated by his growling stomach.

"Sharrif is a very proud kid, he never liked to ask for anything," said Garrett, Washington's former strength coach who met Floyd his freshman year. "We bonded because we're from similar backgrounds. He never quit in the weight room, and that's where our relationship took off. I remember a day it snowed, in the middle of the week, when I got a call. Sharrif shoveled Mike's house and called asking if he could shovel my house for some food money.

"He literally had nothing to eat, so I told him, 'Come on by, I got you.' Sharrif never wanted to ask anyone for anything. I look at him as my younger brother. There were times Sharrif didn't have a place to sleep. His pride prevented him from going to anyone with his problems. He tried the best he could to solve them himself. I'm pretty proud of him for that."

So is Wallace. He was a senior when Floyd was a freshman at Washington. Their bond grew tighter Floyd's sophomore year when Sharrif tore his ACL in the Public League semifinals against Overbrook.

"I remember Sharrif walking everywhere," Wallace recalled. "One time, I was working the night shift at Best Buy, and Sharrif called me in the middle of the night. We just spoke and he mentioned how long he hadn't eaten. He would go days wondering where his next meal would come from. He never asked for anything. One day, we must have had 2 feet of snow and he called to tell me he's on his way to shovel my house. There was Sharrif at the front door. He shoveled the snow and I gave him some money, then he went to shovel more houses."

Frankford, Wallace explains, could be a sinkhole for kids like Sharrif.

"Guys either go to jail or they're dead - and then you have Sharrif. He took what happened to him and made the best of everything," Wallace said. "He could be angry at the world. His determination to be successful changed that. Sharrif was around the drug game early in his life and he saw where that life leads you. If it wasn't football, he'd be successful at something else."

Dawn Reed-Seeger, now at Lincoln, was a guidance counselor at Washington High from 2002-11, with a short stint mixed in at Shallcross. Cohen introduced Seeger, or "Seegs" as Sharrif liked to call her, through a program at Washington called "Play it Smart," intended to support players academically and emotionally.

The Washington football team would gather in the library the day before games and Seeger would cook the team meal. She never missed a game. Gradually, the once-reticent kid with the radiant smile began opening up to her, especially after the ACL surgery.

If something was going on at home, and drama churning constantly in many of the players' lives, they could always lean on "Mama Dukes" as the sympathetic figure.

What forged the bond between Floyd and Seeger goes back to that day. If there is a day that changed Floyd's life, according to all his supporters, it's the day Floyd found out through an aunt that the man he believed was his biological father wasn't. Seeger was at a mall helping kids look for summer jobs when she received a call.

"Devon, my daughter, called me from my home and told me Sharrif was there in tears," Seeger recalled. "When I got home, he was devastated. We shared things before, but at this point, he was a mess. He was extremely upset to the point where he was sweating and crying. We're talking about mid-December, his junior year, before Christmas break. We had to go to City Hall the next day to be honored by the mayor for being city champions."

Wallace stopped by Seeger's home to find Floyd, arms folded across a table, with "a look in his eyes I never saw before," Wallace said. "Sharrif was angry. A part of me was angry and it was amazing and that's when I began asking questions. The guy we thought was Sharrif's father wasn't really a good guy. Sharrif looked me straight in the eye and said he was never going back to live with that man again."

Seeger notified the Department of Human Services the next morning, then Washington's principal.

A few weeks later, Floyd went to the U.S. Army All-American Combine in January 2009 lugging those emotional bricks. Still, he excelled. It's where Floyd was "discovered." Seeger helped raise money for the trip, along with Lahn's financial aid, by enlisting special-education kids to sell brownies.

For a time, Floyd lived with Seeger and her family, with permission from Floyd's grandmother. He stayed with Seeger until the latter part of the second semester of his junior year, when he told Seeger he was moving back with his grandmother.

"Sharrif was very independent; he left telling me he was going back to 'Ma's' house but there was, and is, an attachment there," Seeger said. "I know Sharrif loves us and I love him, and that will never change, but Sharrif really survived on his own. I know, even today, I'm not his mom, but I feel about him the same way I feel about my biological kids. He knows I have his back.

Lahn met Floyd his junior year through the Student Athlete Mentoring Foundation (SAM). Through time, and trust, a relationship developed.

Originally from Long Island, N.Y., Lahn, a University of South Carolina graduate, is self-made, like everyone else around Floyd. He lives in Kennett Square, Chester County, and made his money as a commercial real-estate developer who builds strip malls.

"There was some suspicion at first, I remember," Lahn recalled. "Most people look to get something out of helping others. I didn't. I didn't need the money; I don't need the money now. The thing was, from my standpoint and the way I was raised, my parents would give their last piece of bread to me before they would think about themselves. My family took in a foreign-exchange student who became a part of my family, so it wasn't anything unusual for me to do the same."

The barriers broke. Floyd's inner circle found that Lahn had taken in other kids, less talented kids. He's the legal guardian of Hendrix Emu, 20, a Nigerian basketball player whom Lahn helped get political asylum in the United States.

He now finds himself part of the Floyd family, with Cohen, Odom, Garrett, Wallace and Ma. Lahn adopted Floyd at great personal sacrifice, too.

SAM worked with 50 kids, one of whom, Damiere Byrd, went to South Carolina. That stirred an NCAA investigation, as did Lahn's involvement with Floyd, who went to Florida. The Byrd fiasco forced South Carolina to cut its ties with Lahn. It was a rebuke that stung Lahn deeply. He'd helped pay for Floyd's college visits, and that selfless act got Floyd suspended for two games by the NCAA in 2011. Floyd was told to repay the $2,700 he used for traveling expenses to charity.

"If I was a South Carolina 'guy,' why didn't all of the kids I was dealing with go to South Carolina?" Lahn asked. "Why didn't Sharrif go there? I know I meant well, and deep down inside, I would do everything over again. I'm in a good spot in my life right now. I made a commitment to someone and I wanted to see it through.

"I had to do something. Me and my wife don't have any kids of our own. There are a lot of good kids that need a home. We decided to do this. This is stuff I never dreamed of, having a father-son relationship, and I'm learning on the job. I'll have to admit, I was hurt by the South Carolina thing. I put out a lot of money for that university and they basically turned their back on me. I lost an alma mater, but I gained a son. I think I got the better of the deal. I feel vindicated. I always knew I was doing the right thing. It was something that needed to be done. I wouldn't change anything."

Floyd calls Lahn "Pop." He has provided Floyd with luxuries that he never had before in his life. A lot of Floyd has rubbed off on Lahn, too. His iTunes catalog is filled with Rick Ross raps. One of the more poignant moments together came when Lahn and his family took Floyd, then 20, to Disney World.

Floyd got to live the childhood he never had.

"Sharrif is just a big kid who loves everybody," Lahn said. "You should see him with little kids. It's like he becomes one of them. He wants to be a father, the kind he didn't have growing up."

The final stage

Lahn is renting a bus to go to New York on Thursday. Cohen will be going up with Odom, Garrett, Wallace and Ma. It will be an emotionally charged night. Sharrif probably won't be on the draft board very long.

"I think Floyd is the best and most gifted free technique in this year's draft, which is a position Warren Sapp made famous," said Mike Mayock, the NFL Network's draft analyst. "In a four-man front, Floyd is a defensive tackle that lines up on the outside shoulder of the guard, and typically, that's your interior disrupter. This guy is gifted because of his quickness and explosion.

"At 297 pounds, he ran a 4.9 true 40, which is ridiculous for a man that size. His 10-yard split time was a 1.70, which was probably the best of all the defensive tackles. That to me confirmed everything I saw on tape. To me, Floyd is one of the three best players in this year's draft. I believe he would be a real possibility with Oakland and fits what Oakland does. It wouldn't surprise me at all if the Raiders put his name in as the third overall pick. I can see them thinking Sharrif is going to be the guy they build around going forward."

The Eagles, who pick fourth, are also keeping an eye on Floyd, if he's available.

"Floyd is someone we know a lot about. As a matter of fact, he was in the [NovaCare] building when he was in high school," Eagles general manager Howie Roseman said. "He brings a tremendous amount of versatility and can line up in a variety of spots. He's a tremendous football player, with tremendous character."

Floyd is bracing for the moment his name is called. He knows it's going to come early. He feels it. But there is one thing still missing in his odyssey: Dreams. He feared dreaming when he was young, because every time he did, those dreams would end in disappointment.

"I think what's kept me going is always knowing someone has it worse than I did," Floyd said. "I don't take a lot of credit for things. It's the people around me who helped me get here. And there are a lot of them. Draft night is going to be emotional, I know that. I have no dreams, though. I don't have the world. I'm not done yet. I still have to prove myself. I have to be my own worst critic. No one is going to push me like I push myself. I think that's where the drive has come from. I wouldn't change anything that's happened to me. But it is a great time in my life."