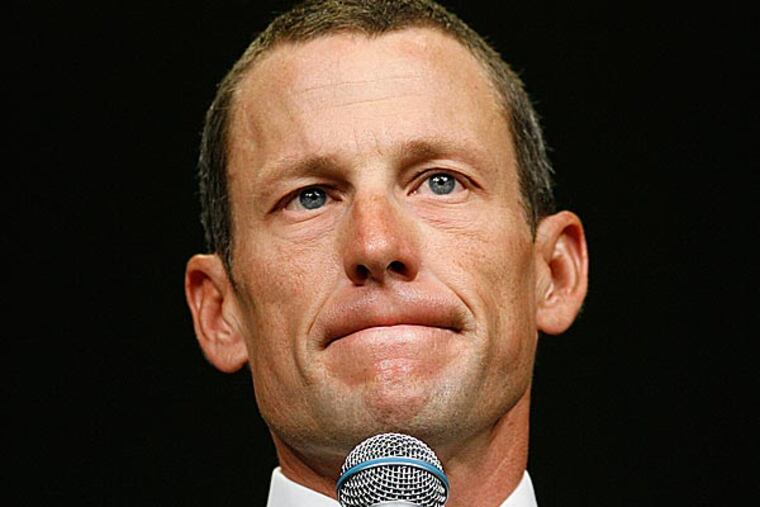

Lance Armstrong: The man who never forgave anybody now wants forgiveness

Just to be clear, no one summons the warm, mothering arms of Oprah Winfrey in order to confess. They do it to be forgiven.

Just to be clear, no one summons the warm, mothering arms of Oprah Winfrey in order to confess. They do it to be forgiven.

That is what Lance Armstrong hopes he will receive from his admissions to be televised later this week on the Oprah Comfy Couch Network. He wants to be forgiven.

He wants to be forgiven by Oprah. He wants to be forgiven by you. He wants to be forgiven by Nike and Oakley and Michelob Ultra. And he really, really wants to be forgiven by the World Anti-Doping Agency.

That's a lot of absolution for one man to seek, but Armstrong was never shy about going after what he wanted. He cheated and he lied, and he climbed some of the steepest mountains on a road paved by that cheating and the lying.

Anyone who crossed Armstrong, even in the slightest way, felt the sting of his retribution. When he contracted cancer and his bike team dropped him, he didn't forget. When teammates left his teams to join others - if they didn't have the blessing of the patron - he would make sure they were hunted down on the roads and not allowed to succeed.

If there were accusations about his methods in the press, he sued for libel (and won). When an insurance company tried to withhold a bonus for winning five consecutive Tour de France titles because of the mounting evidence that he was doping, Armstrong took that case to court (and won).

An enemy of Armstrong could expect three things: There would be retribution, there would be a long memory, and there would be no forgiveness.

That's a key point to remember about Armstrong as the court of public opinion - with other, more formal, courts to follow - focuses on what Armstrong says on Oprah's television network, assuming anyone can figure out whether they actually get the channel.

Armstrong, who never forgave anyone for anything, wants to be forgiven.

Well, isn't that interesting?

Just like a bicycle wheel, what goes around has come around for Armstrong. The competitor who bullied his way through the sport and laughed at the weaker ones is reduced to crawling to regain a shred of the standing he once had. The old Lance Armstrong would have made raucous, profane fun of someone who went running to Oprah. This is the new Lance Armstrong, however, and how revealing that the hardest man looked for the softest pillow to land on.

Armstrong took the honesty route - and it remains to be seen just how forthcoming he actually was - only when he had no other option. When the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency released its 1,000-page investigation last year, which included overwhelming details of his systematic doping, Armstrong received a lifetime ban from competition and also lost the last few supporters who had staked their faith on his steadfast lies.

No more $10,000 speaking engagements. No more lucrative sponsorships. No prospect of more glory, and more fame, and more endorsements, by winning the Ironman Triathlon championship, his next goal.

Cornered by his past, Armstrong wants to paint himself a doorway and make another escape from the pack that caught him. He looks around and sees other athletes who have pulled it off. Mark McGwire confessed, and there he is on a baseball field. Why can't that work for him?

Well, it might, but the odds are considerably longer, and the cost of losing would be huge. Armstrong is very likely going to be the subject of a federal civil suit that will center on the $30 million to $40 million paid by the U.S. Postal Service for sponsorship of his racing team. The government has no sense of humor about that sort of thing.

He could have to pay back the money he took from the Sunday Times of London and from SCA, the insurance company that tried to keep his bonus, and the government of South Australia would like to speak to him about the millions of dollars in appearance fees it paid for his participation in the Tour Down Under. (Lance will win that one, though, because, well, he did appear.)

It is a perilous route he has chosen, and not one that looks promising. The WADA's code stipulates that lifetime bans can be reduced (and only to a minimum of eight years) only if the confessor brings some new information. For Armstrong to do that, implicating himself isn't enough. He would have to give up others not already touched by the scandal. It is a list that could include his closest business associates, and, if the confession is really complete, the list would reach as high as the highest offices of the UCI, cycling's world governing body. If, as Armstrong's teammates have testified, he always knew when the drug testers were coming, there is something there to confess as well.

There is the standard static that will buzz about this whole subject. What about the fact that cycling was dirty and he was just doing what everyone else did? What about all his good work for cancer survivors? Doesn't that count for anything?

He will try to gain traction there, you can bet on that, but the real issue is about Lance Armstrong and the long lie. It finally caught him on the last uphill and left him seeking forgiveness from the Oracle of O.

The real issue is about basic character, and the man who boasted until so recently that he never failed a test has failed that one badly.