Another Roy deserves prominence

In about the time it takes to sign a multimillion-dollar contract, the Phillies' 2010 season has suddenly become the Year of the Roy.

In about the time it takes to sign a multimillion-dollar contract, the Phillies' 2010 season has suddenly become the Year of the Roy.

First there was Roy Halladay. Recently, he was joined by Roy Oswalt, another star pitcher. Wherever the Phillies finish the season, the two Roys will have a lot to do with it.

It's not that the Phillies haven't had Roys before. There was Roy Thomas, the fine turn-of-the-century outfielder from Norristown. There were also Roy Sievers and Roy Smalley, to name a few. But this year's Roys give the name a special meaning.

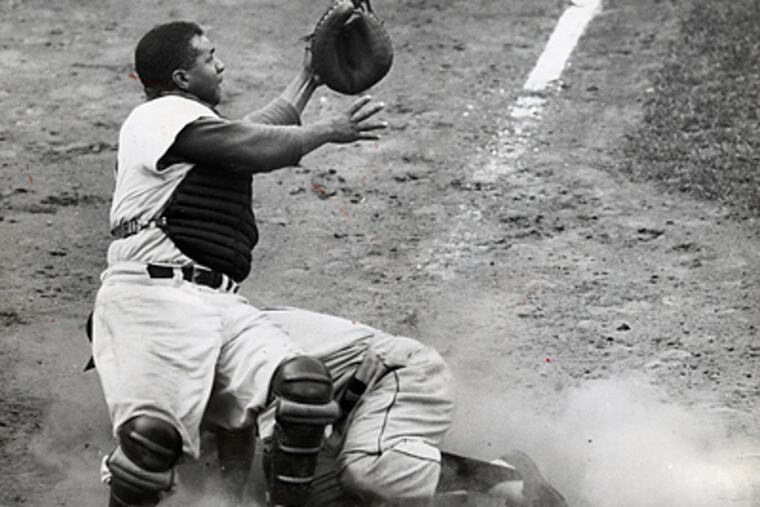

Philadelphia once had another prominent baseball player named Roy - Roy Campanella. A member of the Baseball Hall of Fame and a three-time most valuable player in the 1950s, "Campy" ranks as one of the greatest catchers of all time.

Campanella had been a star in the Negro Leagues for years before he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1948, a year after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Although he never played in the majors for a hometown team, Campanella was a Philly guy through and through.

The son of an Italian father and an African American mother, he was born Nov. 19, 1921, and grew up in the Nicetown section of Philadelphia. He spent most of his formative years living with his parents and brother and two sisters in a corner house at 1538 Kerbaugh St.

His bedroom was decorated with pictures of baseball stars, including ones of the great catchers of the era, major-leaguers Mickey Cochrane and Bill Dickey, and Negro Leagues backstops Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey, who spent a large part of his career in Philly, playing for teams like the Hilldale Daisies in Darby and the Philadelphia Stars between 1923 and 1935.

As a youth, Campanella played stickball and other street games. By age 9, he had jobs delivering milk and newspapers, cutting grass, and each morning helping load his father's truck with produce.

Campanella's baseball prowess was already evident when he played at Gillespie Junior High School on Hunting Park Avenue, as well as with a local American Legion team from the Loudenslager Post and eventually with a fast-paced club called the Nicetown Colored Athletic Club.

He also traveled frequently to nearby Shibe Park to watch the Phillies and across town to see the Philadelphia Stars play at their ballpark at 44th and Parkside in West Philadelphia, paying particular attention to Mackey, like him, a future Hall of Famer.

By the time Campanella was 14, strong and mature for his age, he had attracted the attention of the Bacharach Giants, a prominent African American traveling semipro team from the Philadelphia area.

In the summer of 1937, he began playing for pay with the Giants, earning $15 a game, tutored by the team's starting catcher, Tom Dixon.

Campanella had found his lifetime position.

Before the summer ended, Campanella made another leap. Mackey, by then the manager of the Baltimore Elite Giants, asked Dixon if he knew of anyone who could become his backup catcher. "You're standing right next to him," Dixon said. "Biz Mackey, meet Roy Campanella."

So, not quite 16 years old and only a freshman at Simon Gratz High School, Campanella had become a member of one of the top teams in the Negro National League, earning $60 a month and profiting from the constant guidance of Mackey. "Nobody ever had a better teacher," Campanella said many years later.

Mackey soon moved on to the Newark Eagles, allowing his successor's exceptional talent to blossom. Campanella led the Giants to the 1939 league championship against Gibson's Homestead Grays, smacking five hits, including a home run, and driving in seven runs in the four playoff games.

In 1941, Campanella, still only 19, was named Most Valuable Player in the Negro Leagues' East-West All-Star Game. By then, he had surpassed the aging Gibson as the leagues' premier catcher.

As early as 1942, when World War II had depleted the big-league player pool, Campanella and several other black players were offered a tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates. The invitation, however, was abruptly withdrawn by owner Ben Benswanger, who cited unspecified "pressures."

Campanella, who had never been given any attention by the Phillies, asked the hometown team several times for tryouts. Once, while attending a game in 1942, he even walked down from the grandstand to field level to ask Phillies manager Hans Lobert for a tryout. Lobert, who knew Campanella, suggested he call team president Gerry Nugent.

Using a phone in the ballpark, Campanella made his case to Nugent, but was turned down. There was an "unwritten rule," Nugent said, that prevented blacks from playing in organized baseball, and he was "powerless" to do anything about it.

Before the 1946 season, Brooklyn general manager Branch Rickey signed five black players, including Campanella. Though he was well-equipped to play in the major leagues, Campanella was assigned to Nashua of the Class B New England League. He was the league's MVP, and was accorded the same honor the next season, playing at Montreal of the triple-A International League. He began the 1948 season in triple A with St. Paul of the American Association, but was soon summoned to Brooklyn, becoming the first black catcher in the major leagues.

"I ain't no pioneer," he said at the time. "I'm a ball player."

For all his ball-playing experience, he was still only 26 and in his prime. He quickly became the Dodgers' No. 1 catcher, and despite numerous injuries - including one when a water heater exploded in his face - he would hold that spot for nine years.

He earned positions on eight all-star teams, helping the Dodgers to five pennants and one World Series victory, and winning MVP awards in 1951, 1953 and 1955.

Although he hit as high as .325 (1951), his best year came in 1953, when he led the league with 142 RBIs to go with a .312 batting average and 41 home runs.

On Dodgers teams that had four future Hall of Famers (the others were Robinson, Duke Snider and Pee Wee Reese), Campanella was known as much for his leadership, enthusiasm, and love of the game as he was for his outstanding hitting and catching.

"It's a man's game, but you gotta have a lot of little boy in you to be a good ball player," he said.

Campanella's career came to an abrupt and tragic end in January 1958, just when the Dodgers were preparing to move to Los Angeles. As he was driving to his home on Long Island, his car skidded on ice, struck a telephone pole, and flipped over, pinning Campanella behind the steering wheel. He suffered multiple fractures in his vertebrae and was paralyzed from the shoulders down.

His numbers - a .276 batting average with 242 home runs and 856 RBIs in 1,215 games - told only part of the story of his career. He was an astute handler of pitchers and was regarded as the soul of Dodger teams.

"Just seeing him back there made you a better pitcher," Brooklyn pitcher Johnny Podres once said.

Sitting in his wheelchair, Campanella was a fixture for 20 years at the Dodgers' spring training camp in Vero Beach, Fla., imparting his wisdom to the team's young catchers.

He died at age 71 in 1993 of a heart attack.

Even late in his life, Campanella never showed any bitterness over the accident that deprived him of the final years of his career. "Every night when I go to bed," he said, "I pray to the Lord and thank him for giving me the ability to play ball."