He belted historic home run

Bobby Thomson, the humble, Scottish-born outfielder whose 32d home run in 1951 became the most famous in baseball history, helping, in the famous phrase broadcaster Russ Hodges ecstatically repeated five times, "the Giants win the pennant," died Monday at 86 in Savannah, Ga.

Bobby Thomson, the humble, Scottish-born outfielder whose 32d home run in 1951 became the most famous in baseball history, helping, in the famous phrase broadcaster Russ Hodges ecstatically repeated five times, "the Giants win the pennant," died Monday at 86 in Savannah, Ga.

The cause of death was not immediately known, but his daughter, Megan Thomson Armstrong, said her father had been in failing health and had fallen recently.

Mr. Thomson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World" was struck at 3:58 p.m. on Oct. 3, 1951, in the ninth inning of the third and deciding game of a playoff series between the archrival New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers. It came off reliever Ralph Branca and gave New York a 5-4 victory.

The two men, both of whom grew up in a New York City where three baseball teams balkanized the metropolis' passionate fans, were immediately and forever linked as the ultimate examples of sports' good and bad fortune.

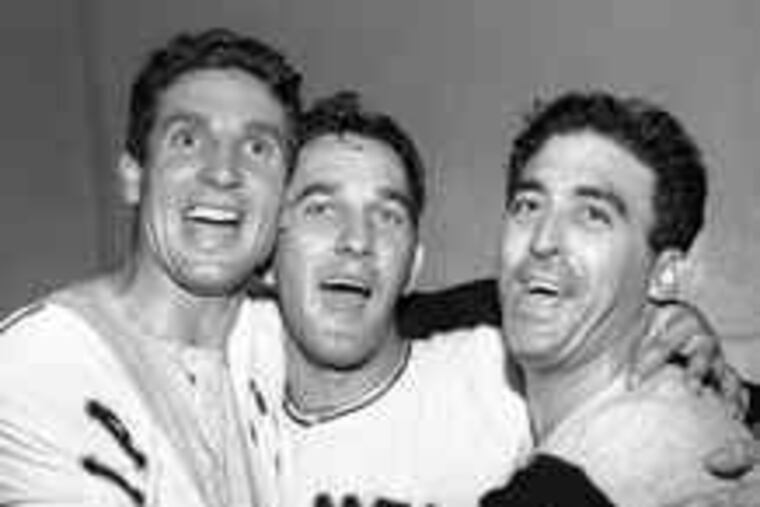

As Branca walked slowly off the trash-strewn Polo Grounds field that day, collapsing in grief on the clubhouse steps, Mr. Thomson leaped into the joyful center of perhaps baseball's first modern postgame celebration, a chaotic scene in which players, fans, and police converged on home plate.

"Now it is done," legendary sportswriter Red Smith wrote in his column from that game. "Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again."

Within days, the hero and goat of the "Miracle at Coogan's Bluff" were guests on national TV shows, and in the decades that followed, Branca and Mr. Thomson often appeared in tandem at banquets, old-timers games, and autograph shows.

The homer, which overcame a 4-2 Dodgers lead in much the same way the Giants had overcome a 13-game Brooklyn lead late that season, on several occasions has been voted baseball's most memorable play. A Sports Illustrated poll named it the second-greatest moment in all of sports, topped only by the underdog U.S. hockey team's upset of the Soviets at the 1980 Olympics.

"I can remember feeling as if time was just frozen," Mr. Thomson once said. "It was a delirious, delicious moment."

So embedded is his homer in the American sports consciousness that even recent suggestions that it might have been tainted have done little to tarnish its reputation.

In 2001, and again in his 2006 book, The Echoing Green, the Wall Street Journal's Josh Prager reported that the '51 Giants, using a telescope in their center-field clubhouse, had been stealing signs and that a reserve catcher had relayed Branca's pitch selection to Mr. Thomson.

Mr. Thomson eventually acknowledged his team's sign-stealing, but always denied that he knew what Branca was going to throw on that pitch. Curiously, he had homered off Branca in Game 1 of that three-game playoff.

Manager Leo Durocher's Giants went on to lose the World Series to Casey Stengel's New York Yankees, four games to two. Mr. Thomson went 5 for 21 with no homers and two RBIs.

Overall, that 1951 season would be the best of Mr. Thomson's fine 15-year career. Playing both the outfield and third base, he batted .293 with 32 homers and 101 RBIs.

Traded to the Braves before the 1954 season, the remainder of his days in the big leagues would be, understandably, anticlimactic. He also played for the Giants again, the Cubs, and Red Sox before finishing in 1960 with the Baltimore Orioles.

A three-time all-star, he hit 264 home runs, drove in 1,026 runs, and had a career average of .270. Still, despite those numbers and the immortality his home run brought him, Mr. Thomson never earned more than 4.6 percent of the writers' votes in Hall of Fame balloting.

Mr. Thomson, the youngest of six children, was born on Oct. 25, 1923, in Glasgow. His father, a cabinetmaker, emigrated to New York when Mr. Thomson was 2.

Taught baseball by an older brother, the Staten Island resident was a high school star before serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II.

In 1942, the Giants, eager to unearth wartime talent, signed him to an amateur contract. By 1946, he was in the major leagues. A year later, Mr. Thomson was a regular outfielder, hitting .283 with 29 homers and 85 RBIs. He combined for 68 homers and 257 RBIs over the next three seasons.

Midway through the 1951 season, with the Giants badly trailing the Dodgers, Durocher installed the slumping Mr. Thomson at third base for the injured Ray Dandridge and put rookie Willie Mays in center field.

Mr. Thomson rediscovered his stroke there, hit .350 over the final two months, and helped fuel a remarkable Giants comeback. Trailing Brooklyn by 131/2 games on Aug. 11, the Giants got hot. At the regular season's conclusion, the two New York teams were tied atop the NL with 96-58 records.

His first homer off Branca gave New York Game 1 of the unprecedented three-game playoff by a 3-1 margin. Brooklyn's Clem Labine shut the Giants out in Game 2, 10-0, setting the stage for the memorable moment.

The Dodgers led, 4-1, entering the bottom of the ninth and seemed on the verge of their third pennant in four years. But Brooklyn starter Don Newcombe, who had thrown 142/3 innings on the regular season's final two days, was tiring.

Alvin Dark and Don Mueller singled to start the inning. One out later, Whitey Lockman doubled in Dark and moved Mueller to third. (Mueller slid awkwardly, hurt an ankle, and was replaced by Clint Hartung.)

Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen finally decided to pull his starter. Branca and Carl Erskine were warming up. When bullpen coach Clyde Sukeforth indicated the latter had bounced a warm-up curveball, Dressen opted for Branca, who had started and lost Game 1 two days earlier.

With Mays on deck, Thomson took a fastball for strike one.

At that moment in the crammed press box, a confident Dodgers official announced, "Attention press, World Series credentials for Ebbets Field can be picked up at 6 o'clock tonight at the Biltmore Hotel."

On the field, Branca went with another fastball, up and in, and Thomson lashed at it.

"I kept telling myself, 'Wait and watch. Give yourself a chance to hit,' " Thomson remembered.

The line drive hissed toward the short left-field wall. As leftfielder Andy Pafko retreated, it cleared the 315-foot sign and disappeared into the stands.

In a Polo Grounds radio booth, Giants announcer Hodges made his memorable call.

"There's a long drive . . . It's gonna be . . . I believe - the Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! . . . Bobby Thomson hits into the lower deck of the left-field stands! The Giants win the pennant and they're goin' crazy, they're goin' crazy!"

As Branca and his stunned teammates trod off the field, Mr. Thomson danced around the bases before thrusting himself into the growing clot of humanity awaiting him at home plate.

"I watched the homer but not the celebration," Rube Walker, a Dodgers backup catcher that day, said in 1994. "God, that was the toughest moment in my career."

Fifty-nine years later, the memory has barely faded. The U.S. Postal Service in 1999 issued a stamp commemorating it. Two years earlier, author Don DeLillo used it as a focal point of his acclaimed novel, Underworld.

The ball that Mr. Thomson hit, which collectors believe would be the Holy Grail of sports collectibles, has never been located. In his 2009 book, Miracle Ball, author Brian Biegel speculated that it might have been caught by a nun who had slipped away from her convent to attend the game. She died recently in Arizona, and her belongings were disposed of at a nearby landfill.