The Bill of Writes: Conlin, the choice voice of Philadelphia baseball, to be honored

"Did I mention one of the ways a fringe pitcher can shorten his big-league career? Well, he can get his general manager arrested for disorderly conduct, which is what happened to Paul Owens after a 1981 cocktail-lounge altercation in Chicago . . .

"Did I mention one of the ways a fringe pitcher can shorten his big-league career? Well, he can get his general manager arrested for disorderly conduct, which is what happened to Paul Owens after a 1981 cocktail-lounge altercation in Chicago . . .

"After failing as an arbitrator during that stormy scene, I had to dash upstairs and write the story.

"Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall make deadline."

- Bill Conlin

ON THE WAY to the 1988 Winter Olympics, the nation's sports editors arranged a splendid series of economical flights for us: Philadelphia to Chicago, Chicago to Spokane, Spokane to Calgary. I was in a middle seat the whole way. Bill Conlin was on the aisle.

It was February. There were weather delays. Refreshments were served promptly and throughout. Somewhere over Indiana, Conlin had to move so I could get to the restroom - somewhere over Indiana, and then over Iowa, and then again over Wyoming. The fourth time, probably over Lethbridge, he looked at me and said, "No wonder I'm so fat - I never have to go."

He said something else on that flight that I have never forgotten. After the Olympics ended, the Daily News was going to make me a columnist. The gist of Conlin's advice was, "They're doing this because they want to hear what you have to say, not what the athletes have to say."

I was 29 years old. I could not imagine having the confidence in my words that Conlin had in his. All of these years later, there are still some days that I cannot imagine it.

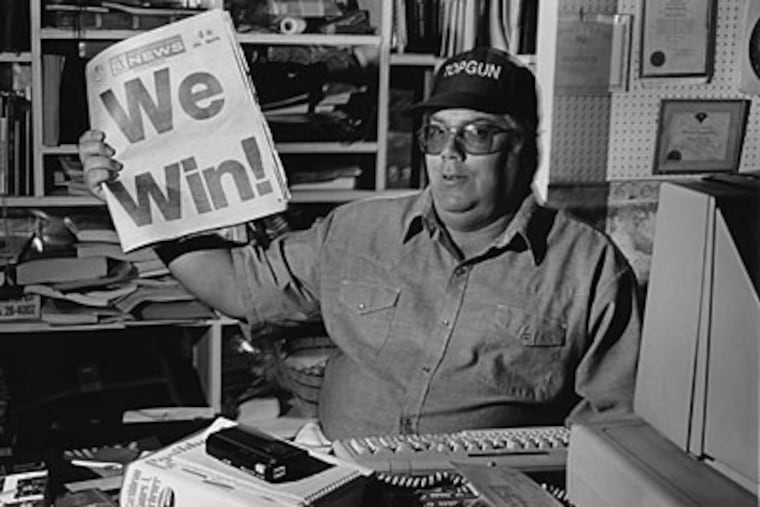

Conlin is being honored this weekend at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. He is receiving the J.G. Taylor Spink Award, a lifetime achievement award for baseball writers. Chosen by his peers in the Baseball Writers of America, it is a distinction earned over decades - in dugouts, learning the game; in airports, surviving the game; in press boxes and then in the paper the next day, respecting the game.

But in Conlin's case, it is more than that. He is being honored because of that literary voice, one that has defined Philadelphia baseball for so long: loud, stylish and unshakable, even today.

"Connie Mack Stadium is an old woman dancing nude at the Medicare Senior Prom. You know what she once might have been, but tonight she is an obscene accordion of yellowed flesh.

"Connie Mack Stadium is a joke played by a 1909 high school class in Architecture. At its best, the architectural style could be described as St. Louis World's Fair Lavatory. It makes City Hall look like the Palace of Versailles."

- Oct. 1, 1970, on a ballpark's demise

"The Dodgers were down to their suspect bench. Ancient Vic Davallio hauled his well-traveled bones to the plate, more wrinkles on his leather face than there are base hits left in his bat. On deck was Manny Mota, 39 years old, one final straw for Tommy Lasorda to clutch at should Davallio reach first base.

"Thus began the shortest, most devastating nightmare in the history of a town steeped in an athletic tradition of flood, fire and famine, a town where down had often seemed a long way up.

"The Phillies' 1964 collapse took ten games. This one took ten minutes. It was like watching the shambles of 1964 compressed into an elapsed-time film sequence."

- Oct. 8, 1977, on Black Friday

Three things have made Conlin: the confidence, the obvious writing talent, and the times in which he established himself as the Phillies' beat writer for the Daily News, 2 decades that spanned from the mid-'60s to the mid-'80s.

Back then, the Daily News was an afternoon paper. For most of Conlin's time on the beat, the copy deadline was about 5 a.m., or later. He would generally write one story per day, with some notes tacked on to the end that he called "Philups." He would file that story, routinely, after 3 a.m.

Early on, there was a decision to make. Most baseball writers get to the park at 3 p.m. and begin reporting in the clubhouse soon after. By careful scientific measurement, approximately 82.6 percent of that time is a complete waste of time, but you do it for the other 17.4 percent of the time when something might actually happen.

But as a writer for an afternoon paper, Conlin had to make a choice. To get there at 3 p.m. and write until 3 a.m. meant a 12-hour day, 6 days a week for 6 months for decades. No one would do that. He also wasn't going to give up the writing time, because that is why he was in the business. So he routinely skipped much of the pregame, confident that he could pick up what he needed after the game in the clubhouse - where he could stay longer than any writer, because of those deadlines - and knowing that the desk guys in the office would be reading the early edition of the Inquirer while the ink was literally still wet and calling him if one of their beat men, such as the great Jayson Stark, had anything he needed to chase.

It was a system perfect for the man - and for the people who read him - because it allowed Conlin to focus on the two things he most cared about: the games and the words.

As the writers arrayed around him typed like madmen against early deadlines, Conlin could watch and savor what was happening on the field. He learned the nuances of the game at the knee of Phillies manager Gene Mauch, and it was through those trained eyes that he observed.

His goal was to tell his readers why, not what. He would shove the score into the game story, usually, but the rest was his personal canvas. If he wanted to write the whole story about a botched rundown in the fourth inning, peeling the sequence apart like an orange, he would.

In the clubhouse, the insights of the principals in the rundown would be recorded. But that was only the beginning. Because Conlin knew what he had seen but he also knew that there was a group of scouts and broadcasters and team executives gathered around a table and a cocktail in the press lounge at the Vet. Conlin would join them - to learn more, and because he was thirsty.

What would he find out? Maybe the hint of an injury, or the whiff of a trade. Maybe the reminder of a botched rundown of some infamy in the past, or maybe nothing except a few more minutes to order his thoughts. The other writers might or might not join the group, one by one, briefcases and computers packed up, their final deadlines passed.

Only then would Conlin return to the press box and begin to type. It was often past midnight when he wrote his first word.

"Bob Boone gloved the last fastball Tug McGraw had left in his weary arm, and the Phillies erupted joyously into each other's arms - surrounded by new centurions on horseback, helmeted soldiery carrying truncheons, snarling attack dogs and a whooping cast of 65,838 extras aflame with passion, eyes blazing with the town's first World Series title. The scene looked like something Cecil B. DeMille would have filmed in the Promised Land. The Phillies finally arrived there last night with a 4-1 victory."

- Oct. 22, 1980

"Twenty-eight years vanished in the heartbeat it took for Brad Lidge to deliver one final, unhittable slider to Phillies catcher Carlos Ruiz.

"Then, 1980 was suddenly 2008 and it was Lidge, not Tug McGraw, leaping joyously into the gelid South Philly air, and waiting for an avalanche of whooping teammates to engulf him. Brad sank to his knees in a spread-eagle prayer, beckoning toward Ruiz, who leaped into his arms.

"Willie Wilson then, Tampa Bay Rays pinch-hitter Eric Hinske last night. The fathers then, their sons and daughters now. They bellowed the two decades plus 8 years drought away in a celebration that had built up for so long that the nation had been served by four Presidents serving a total of seven terms."

- Oct. 30, 2008

The press box was his place. His debates, loud and long, with Bus Saidt of the Times of Trenton, who sat to his immediate right at the Vet, were curmudgeonly classics. Then there was the time when he was attempting to write a novel and decided to read aloud from his work one night - specifically, every jot and tittle of a multipage sex scene. Since Conlin is genetically incapable of keeping his voice down, let's just say that the people in the 300 level also were unexpectedly entertained. It was hilarious. As he said later, "I'm not trying to win the National Book Award - I'm trying to win the National Buck Award."

But it wasn't all laughs. Conlin has feuded along the way with friends and enemies, rivals and colleagues, players and managers and ownership. It is part of what makes the man. I'll never forget during the players' strike in 1995, when his son Pete was one of the Phillies' replacement players during spring training, and the father quoted the son in a column as saying, "Hey, if I pitch and I stink, rip me. I hear it's an honor."

For me, two great controversies stand out. The first was in the 1970s, when lefthander Steve Carlton stopped talking to Conlin, and then later to the rest of the media. It all began because Conlin hinted that, during a down stretch, Carlton might have been hitting it a little too hard in the postgame hours - a fact that he knew firsthand. Carlton was hoping for some discretion. Conlin said the truth was his defense - and besides that, he didn't tell the half of it.

The other controversy is less remembered but more significant. In the mid-1980s, Conlin was first and alone in writing that the Phillies' farm system was being mismanaged into ruin. For several years, a very long time, he was by himself on the story - all by himself. The club was furious and in denial, and did its best to marginalize him, but he kept hammering away. The farm system ultimately imploded upon itself and Conlin was proven correct on the story of the decade for the franchise, but it had to have been a lonely time.

These days, Conlin's current feud is with bloggers, what he calls "dot-commers," as well as sabermetricians. It really is a different world. I'm not sure what kind of newspaper beat man a young Bill Conlin would have made in 2011: wake up, blog, get to the park early, write a pregame notes story for the website, blog, write notes for the paper, Twitter during the game, spend only about 20 minutes in the clubhouse, file the game story by 11 p.m., maybe touch it up for the last edition, shoot a short video, blog.

Given the current demands, nobody is ever again going to cover a baseball team for 20 years. And the great irony is that the people who have the best chance in 2011 to do it like Conlin did it in 1971 are the dot-commers, like Stark at ESPN.com, who can stay in the postgame clubhouse forever, searching for that singular anecdote, before sitting down to write.

Even with that, they cannot match what has been an undisputed truth in Philadelphia for more than 4 decades. Whenever something big has happened with the Phillies, one question has always lurked among his peers:

What did Conlin write?

It was true then. It is true today. There may have been baseball writers in this town who hit for a higher average, but no one has ever hit them farther.

"As Lefty joins the pastime's immortals, I glow with a perverse pride.

"Me . . . When he first started not talking to the media, I was the object of his ire. Hey, don't I rate a blank plaque or something? To go with all those notebooks Lefty refused to fill."

- Aug. 1, 1994, on Carlton's selection to the Hall of Fame

Send email to

hofmanr@phillynews.com, or read his blog, The Idle Rich, at

www.philly.com/TheIdleRich. For recent columns go to