A chance to own a bit of baseball history

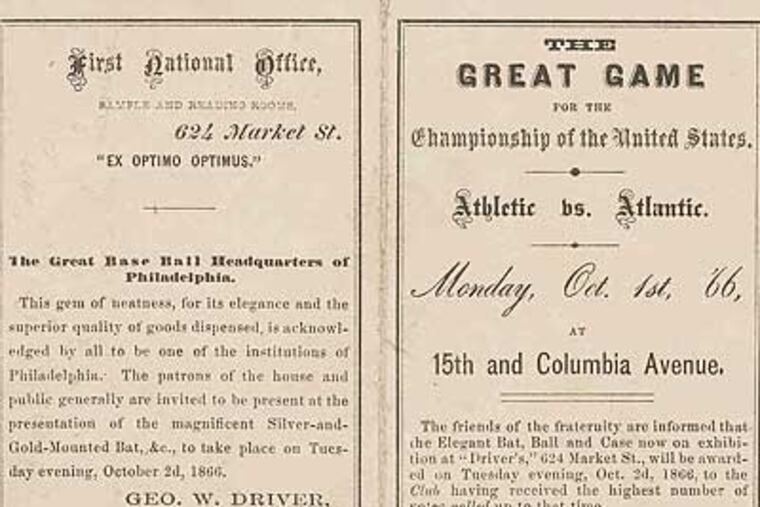

The tiny scorecard ballyhooing "The Great Game for the Championship of the United States" is more than an artifact from what was then, in the autumn of 1866, the most widely anticipated baseball game ever played.

The tiny scorecard ballyhooing "The Great Game for the Championship of the United States" is more than an artifact from what was then, in the autumn of 1866, the most widely anticipated baseball game ever played.

The 51/2-inch-by-4-inch handout, produced on the letterpresses of Haddock & Son Printers, 618 Market St., is also a keepsake from the moment when the legend of the passionate Philadelphia sports fan may have been born.

On Thursday, nearly 145 years after someone penciled in the starting lineups on it, this yellowing baseball relic will be auctioned at Swann Galleries in New York, where experts expect it to fetch $5,000 to $7,000.

"As far as anyone knows," Swann's Rick Stattler said, "this is the first printed baseball scorecard ever."

It was handed out to fans who, in a virtually unprecedented move, were charged 25 cents to watch the Oct. 1, 1866, game between Philadelphia's Athletics and Brooklyn's Atlantics at a 15th and Columbia ball field.

According to various accounts, the promoters had sold 8,000 tickets in advance and, in another exceptional action, some of the nominally amateur players privately had agreed to split the proceeds.

Unfortunately, another 25,000 or so fans flocked to the North Philadelphia site that Monday afternoon, a gathering so large and rowdy that the game had to be canceled after just a half-inning.

"There was just no room to play, and the police couldn't keep the crowds off the field," said Stattler, citing various newspaper accounts. "The first baseman said he didn't have any room to make plays at first base. There are reports that at least one spectator was pulled off with blood streaming from his head. Things got pretty rowdy. Finally, in the bottom of the first inning, when a New York guy hit a ball into the crowd, they decided they just couldn't go any further."

Someone had entered the lineups on the surviving scorecard, presently owned by collector Eric Caren, and filled in the activity from the top of the first. As was commonplace then, the home-team Athletics hit first, scoring two runs that further fanned the huge gathering's fire.

The four-page scorecard itself is rather plain. Though billed as being for the "Championship of the United States," that claim almost certainly was fallacious. Later that same month, a series between Brooklyn and a team from Irvington, N.J., was called the same.

Its cover promotes the game in various typefaces. At the bottom is the beginning of an advertisement for Driver's, apparently a bar at 624 Market St. Continuing on the back page, the ad seems to be promoting a lottery in which the winner was to get an "Elegant Bat, Ball and Case."

Covering both interior pages is a surprisingly contemporary looking scorecard, with spaces for players' names, the outcomes of their at-bats, and the innings.

A few names of the Athletics, who five years later won the championship of the first professional league, the National Association, are familiar. Al Reach, the future sporting-goods entrepreneur and Phillies owner, hit third and played second base; Lip Pike, the game's first Jewish star and one purported to have hit six home runs in a game that July, batted ninth and played third.

Maybe the best-known Brooklyn player, a fame more attributable to his nickname than his abilities, was Bob "Death to Flying Things" Ferguson, an outfielder batting ninth.

Game's best team

In the loosely organized world of 1866 baseball, 10 years before the National League's formation and 17 years before the arrival of the Phillies, many believed the Athletics were the game's best team. They won 23 of 25 games that season, falling only in subsequent contests to the Unions of Morrisania (a Bronx neighborhood) and their great rivals, the Atlantics.

The recently concluded Civil War had fertilized the blossoming game of baseball so successfully that by Appomattox it was almost certainly America's most popular sport. Within four years, more than 500 teams would be registered by the game's regulatory body, also named the National Association.

New York and Philadelphia were the game's original hotbeds. The Oct. 1 game, the opener in what was expected to be a best-of-three series, had been promoted for several days by newspapers in both cities.

Not long after daybreak, fans began trudging up and down Broad Street en route to the field. Accounts vary, but most put the crowd at between 30,000 and 40,000, which made it the best-attended baseball game ever.

The premature cancellation reportedly did not make all those Philadelphia spectators happy, particularly those who had forked over a quarter. Some stories imply, unsurprisingly, that the Atlantics had a difficult time exiting the field.

The scorned visitors got their revenge two weeks later, however, in Brooklyn, winning, 27-17, in front of a crowd of 18,000. The official scorer must have been a stickler, because he awarded 54 errors in the game - 44 by the losers from Philadelphia.

The postponed Philadelphia game was played on Oct. 22. To either take advantage of the demand or try to limit the crowd size, fans were asked to pay an exorbitant $1 admission. By then, fences had been put up around the field.

While 2,000 paid to get inside, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 more surrounded the park. The Athletics won, 31-12, as darkness halted play in the seventh.

Money was an issue

Baseball, like most sports at the time, was considered a pastime for amateur gentlemen. But cracks were appearing, a trend the Athletics-Atlantics series apparently exacerbated.

That same year, there were reports saying the Athletics were paying at least three of their players, including Pike. And once players got the taste of money, and it became clear fans were willing to spend it, amateurism was doomed.

The Cincinnati Reds finally ended the charade and in 1869 became the first true professionals. By 1871, the notion was so widely accepted that a professional league was formed.

But on that Oct. 22, money already was an issue. The Atlantics were unhappy with their share of the Philadelphia gate receipts. They huffed all the way back to Brooklyn, but not before they had announced that they wouldn't be playing the miserly Athletics in any rubber match