A pioneering Phillie lost to history

When it comes to the dangerous intersection of race and sports, T.S. Eliot was right. April really is the cruelest month.

When it comes to the dangerous intersection of race and sports, T.S. Eliot was right. April really is the cruelest month.

It was, after all, in April 1947 when the infamous racist rant Phillies manager Ben Chapman directed at Jackie Robinson took place. And it was in that same month, 67 years later, when we learned about Donald Sterling's bigoted outburst.

The world has changed dramatically between those two Aprils. But, unfortunately, some attitudes have not.

April also figured prominently in another race-related tale, this one a bittersweet Philadelphia story that underscored America's ongoing difficulties in dealing with its oldest and most perplexing problem.

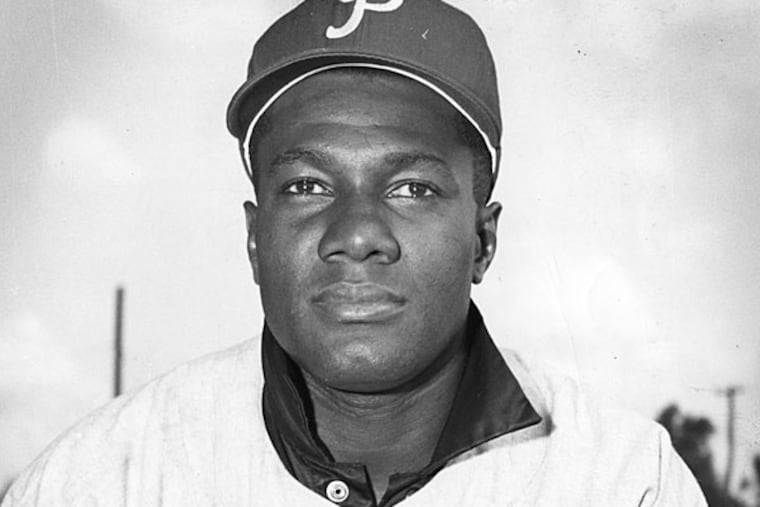

John Kennedy's brief major-league career began on April 22, 1957, the 10th anniversary of a day baseball wanted to forget. What would be forgotten instead was Kennedy.

Twelve days after he became the first black man to wear a Phillies uniform, Kennedy's career was over. And when this history-making infielder died in 1998 - on another April day, of course - he was buried in an unmarked grave.

History is filled with ironies, few more striking than those that marked Kennedy's Phillies debut.

It came on the 10th anniversary of the day when Chapman, who grew up in Alabama, so viciously taunted Robinson. And, as if the event were being staged to mock the Phillies for their pathetic procrastination, it came against Robinson's old team, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Three months before Kennedy's first appearance, Robinson, by then retired, had questioned publicly why, a decade after he'd shattered baseball's color barrier, the Phillies, Tigers, and Red Sox had yet to integrate.

Within weeks, perhaps prodded by the embarrassment Robinson's comments had provoked, the Phillies signed Kennedy, a shortstop with the Negro League's Kansas City Monarchs. Its groundbreaking addition, the team announced, was a 21-year-old prospect. Actually, he was a 30-year-old journeyman.

The Phillies failed to explore their signee's background. Kennedy had played nearly a decade in Canada, in the Negro Leagues, even in the minor leagues with a New York Giants affiliate in St. Cloud, Minn.

That first spring in segregated Clearwater, Fla., Kennedy had to room with a black family and eat alone in the few restaurants that would serve him.

"It would be nice if I had a roomie," Kennedy told a Philadelphia sportswriter that spring. "But I go to the movies a lot and read, and somehow the time passes."

His loneliness didn't impact him on the field. He so impressed the Phils at camp that, in March, manager Mayo Smith told reporters the Jacksonville, Fla., native would be his starting shortstop "if we were starting the season tomorrow."

But between then and the team's April 16 opener something, perhaps the discovery of Kennedy's true age, caused the Phillies to sour on him. They hastily sent five players to the Dodgers for Chico Fernandez, a dark-skinned Cuban, and handed him the shortstop's job.

Kennedy never got off the bench during the Phils' first five regular-season games. Then on April 22, late in a 5-1 Phillies loss to Brooklyn at Jersey City's Roosevelt Stadium, Smith sent him in to run for Solly Hemus, and 74 years of whites-only Phillies baseball was over.

His historic role couldn't save his career, and 12 days later, after just five appearances and two hitless at-bats, Kennedy was demoted to the minor leagues, never to return.

He survived three seasons at Phillies minor-league outposts in Tulsa, Des Moines, and Asheville, before retiring and taking a job in an Ohio steel mill.

In retrospect, Kennedy's signing seems a hasty act by the Phillies, one meant to appease their critics as much as enhance their ball club. Other teams, it appeared, integrated not just more quickly but more thoughtfully, breaking the color line with enduring talents such as Robinson, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Minnie Minoso, Elston Howard, and Ernie Banks.

Still, even considering the Phillies' sorry record in race relations, the end to Kennedy's career was unusually abrupt. Two at-bats is hardly an opportunity. Never told why it had happened, he would be haunted by it the rest of his life.

Eventually, that bewilderment and disappointment infiltrated his subconscious. Shortly after Kennedy's death in 1998, his daughter, Tazena, told The Inquirer that a recurring dream had long tormented her father.

In it, he would arrive at Connie Mack Stadium to find that his Phillies teammates were already taking infield practice. Scurrying to join them, Kennedy couldn't find his locker. Desperate now to inform his manager of his dilemma, he couldn't locate the field.

Despite his disappointment, Kennedy wasn't bitter about his mysteriously truncated big-league career.

"He felt like he didn't get a fair chance to prove himself," Tazena Kennedy told a Jacksonville newspaper in 2008. "But he . . . felt lucky to at least make it to the majors when a lot of other people didn't."

Kennedy's love of baseball never faded. He was playing in a Jacksonville adult league not long before he succumbed to a stroke in April 1998.

Last year, while on an unrelated assignment in Jacksonville, I found Kennedy's grave. I had to be escorted to the plot in Evergreen Cemetery because there is no headstone or permanent marker there.

This year, the Phillies big-league roster has more African Americans than at any time in franchise history. For much of the young 2014 season, their entire starting outfield and half their infield has been black.

While they could not have avoided hearing about the controversy stirred up by Sterling's comments and subsequent banishment, I wonder how many of those Phillies, if any, know the story of John Kennedy.

If they are familiar with it, then perhaps one of them - or, even more appropriately, the Phillies organization itself - could provide a simple marker for this pioneer's grave.

It would be a deserving gesture for a man who never got the chance he deserved.

@philafitz