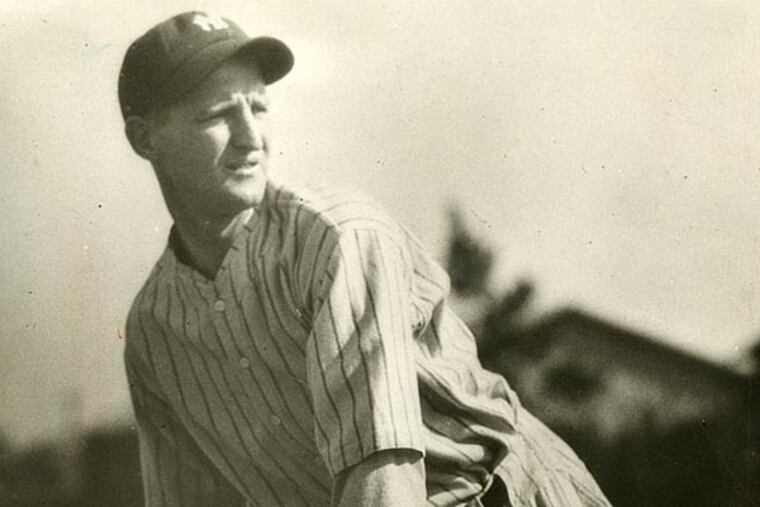

Racism claim still clouds Hall of Famer Pennock's reputation

Much as the sour scent of mushroom compost pervades his old hometown of Kennett Square, the taint from a single conversation clings unpleasantly to Herb Pennock's reputation.

Much as the sour scent of mushroom compost pervades his old hometown of Kennett Square, the taint from a single conversation clings unpleasantly to Herb Pennock's reputation.

Sixty-seven years after his telephone call to a fellow baseball executive, the onetime Phillies general manager and Murderers' Row Yankee is permanently marooned in history's limbo, trapped between what we know of him and what we think we know.

The known is impressive. A Hall of Fame pitcher, Pennock retired in 1934 with 241 victories. In winning four championships as a Yankee, he compiled a 5-0 World Series record with a 1.95 ERA. As a GM, he shaped the pennant-winning 1950 Phillies. As a man, it appears, he was almost universally admired.

"Everybody here loved him," said his grandson, Eddie Collins III, 70, of Kennett Square. "You'll never hear a bad word about him."

But all that has been obscured by a phone call to Branch Rickey in May 1947. Because of it, Pennock is widely seen as a racist obstructionist who demanded the Dodgers not bring Jackie Robinson to Philadelphia.

If true, and many baseball historians believe the story, the criticism appears valid. But so many questions surround the conversation - including whether Pennock was even a part of it - that it seems an unfair basis for so serious a judgment.

On Thursday night at the Sheraton Society Hill, Pennock will be inducted as part of the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame's Class of 2014, along with 15 other individuals and Immaculata's Mighty Macs. His racial views, which continue to be debated, were not considered in the selection process.

"When establishing the Hall . . . it was agreed that on-field performance would be the focus," said Ken Avallon, its president. "We recognized the potential pitfalls of judging where to draw that line so we agreed that there would be no character clause. After all, Bill Tilden [the tennis great who was convicted on morals charges] was in the charter class."

Halls of Fame everywhere have similar policies, admitting all sorts of athletically gifted miscreants. But what separates Pennock from other legends scarred by racism - say, a Ty Cobb or Cap Anson - is the paucity of evidence against him.

Pennock may have been the man the phone call suggests, but there's little else in the public record to support that.

Infamous conversation

Through the years, relatives and friends consistently described "The Squire of Kennett Square" as a sophisticated, open-minded Quaker gentleman. And though it likely was lip service, Pennock told The Inquirer in July 1947, six months before his death, that his Phillies were considering a black player.

It wasn't until the publication of a book nearly three decades later, in 1976, that the infamous conversation came to light and Pennock's reputation darkened.

According to The Lords of Baseball, by longtime Dodgers executive Harold Parrott, the Phillies GM called Rickey before a Dodgers-Phillies series at Shibe Park and, using racially charged language, insisted Robinson not accompany the team here.

"You just can't bring the [racial epithet] here," Pennock allegedly said.

Parrott wrote that he'd heard the conversation on an extension in Rickey's office. His account is now an accepted element of baseball's integration tale, finding its way into subsequent Robinson biographies and a popular 2013 Hollywood film, 42.

Still, doubts persist. Robinson himself, in discussing it years later, said Phils owner Bob Carpenter made the call. One Robinson biographer questions Parrott's reliability as a historical source. And others don't believe the principled Rickey ever would have allowed an underling to eavesdrop on a sensitive discussion with another GM.

Pennock's defense, meanwhile, isn't aided by the Phillies' sorry history on race.

They were the last National League team to integrate, a decade after the Dodgers. On Pennock's watch, those '47 Phils threatened a boycott if Robinson played. And, led by manager Ben Chapman, they savagely taunted the Dodgers rookie.

Given that atmosphere, it's easy to view Pennock, the Phillies' chief executive, as equally culpable.

"I'm not calling Pennock racist, but I do believe there is just as much circumstantial evidence to support [Parrott's account] as there is to reject it," said William Kashatus, a Chester County historian who has written books on both Robinson and the Phillies' race-related legacy.

The principals are dead, the call was not recorded, the books and films inform the national consciousness. The truth about Pennock, whatever it is, may never be known.

Yet some, like the author who has been looking for information about Ebbets Field's telephone system in hopes of debunking Parrott, continue to seek it.

Connie Mack's find

Pennock's ancestors are believed to have arrived in Pennsylvania with William Penn, settling in southern Chester County.

Herb, the youngest of four, was born in 1894. A son of privilege, he perfected his baseball abilities at several boarding schools, including the Westtown School.

In 1912, Connie Mack's A's signed him, and after the lefthander no-hit a traveling Negro League team, he was promoted to Philadelphia. For whatever reason, the young pitcher with the effortless motion failed to impress. In 1915, Mack sold him to the Red Sox for $2,500.

Seven years later, Pennock became one of many players Red Sox owner Harry Frazee shipped to the grateful Yankees. On those Ruth-Gehrig juggernauts, he was a productive mainstay, winning 115 games in his first six New York seasons.

He retired in 1934 and retreated to his 37-acre Kennett Square farm, a site now occupied by the Longwood Shopping Center. He raised hothouse flowers as well as the red-silver foxes he and friends like Babe Ruth often hunted there.

In 1943, after Carpenter's purchase of the team, Pennock was hired as the rebuilding Phillies' GM. Housed in a 19th-floor Packard Building office, he began establishing the scouting system that yielded 1950's pennant-winning Whiz Kids.

Robinson debuted in 1947. That April in Brooklyn the Phillies verbally savaged the rookie. Before the Dodgers came to Philadelphia for three games, May 9-11, commissioner Happy Chandler contacted Carpenter and told him he expected no repeat.

Sometime in early May, according to Parrott, Rickey summoned the secretary into his Ebbets Field office. Talking with Pennock, he motioned for Parrott to pick up an extension.

"[You] just can't bring the [racial epithet] here with the rest of your team," Parrott recalled Pennock saying. "We're just not ready for that sort of thing yet. We won't be able to take the field against your Brooklyn team if that boy Robinson is in uniform."

Pennock eventually backed down when Rickey told him the Dodgers would gladly accept three forfeited wins.

Author Jonathan Eig, whose Opening Day is a detailed account of Robinson's breakthrough, is among those who question the story.

"Parrott is the only source," Eig told The Inquirer. "He wrote that years later and, quite frankly, he hasn't proved to be the most reliable source."

Eddie Collins III doesn't doubt the call took place, but, like Robinson, he believes the man Rickey spoke with may not have been Pennock.

"I think it was Carpenter," said Collins, whose other grandfather, his namesake, is also in baseball's Hall of Fame. (Pennock's daughter Jane married Eddie Collins' son.) "Carpenter had that kind of reputation. Even if it was [Pennock], he owned the team. He dictated what happened."

No statue after all

The following January, at baseball's winter meetings in New York, Pennock, 53, was fatally stricken by a cerebral hemorrhage in the Waldorf-Astoria lobby. Later in 1948, after several near-misses, he was elected posthumously to baseball's Hall.

That was Pennock's last headline until, in 1998, Kennett Square announced it would erect a statue of him at Old Baltimore Pike and Union Street. The proposal died after the local black community, citing the notorious phone call, objected.

Then in 2010, a local author who said he was writing a Pennock biography and identified himself only as "Digger Scribe," posted a query on a website for Brooklyn Dodgers fans.

"Locals around here have long been disgusted that Parrott's singular indictment has cast doubt about Pennock's character," he wrote. "I've taken it upon myself to find the truth . . . Specifically, I'm wondering if the front office at 215 Montague Street, and Branch Rickey's office in particular, had an extension phone. Parrott insists in his book that Rickey motioned him to 'pick up the extension' and listen to Pennock's screed."

Pennock's induction Thursday likely will do little to clarify the issue. The event's program will include an article on the pitcher/GM by David Jordan, who has written several Phillies-related books. What will it say about that phone call 67 years ago?

"I wasn't sure what to say about it," Jordan said, "so I didn't even mention it."

@philafitz