Mike Missanelli: Race is central to Lin's story

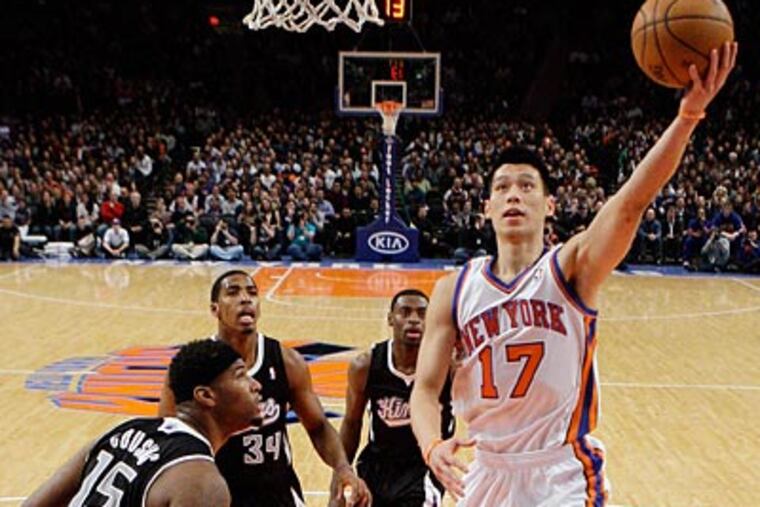

The other night, when Jeremy Lin dribbled a basketball at the top of the key and had the audacity to wave off his New York Knicks teammates - four guys standing around doing nothing while the one, Lin, determined the fate of this particular NBA game - I was hooked.

The other night, when Jeremy Lin dribbled a basketball at the top of the key and had the audacity to wave off his New York Knicks teammates - four guys standing around doing nothing while the one, Lin, determined the fate of this particular NBA game - I was hooked.

We all know what happened. Lin swished a three-point shot to give the Knicks a thrilling victory over the Toronto Raptors and continued on his mission to resurrect New York pro basketball. He also struck a global blow for underdogs. The next game he posted a career-high 13 assists as the Knicks won again. Now, what's done is done. Not even Spike Lee's outstretched leg at Madison Square Garden can trip up a story like this.

Jeremy Lin is a sports tale that comes to us maybe once every 20 years. And I've really never seen anything like it.

The Tim Tebow tale was nice, but nothing like this. Tebow was an accomplished college football player, maybe the best college quarterback ever. Yes, there were doubts as to whether he could play that position in the pros. But at the end of the day, Tebow was a first-round pick. Lin is the kid from nowhere. He's Roy Hobbs dropped in the lap of Pop Fisher with his bat in a violin case. And he's hitting game-winning home runs.

The Lin story has more layers than an Italian wedding cake. And if that's a little too ethnic for you, get used to it, because we're about to have an honest discussion on ethnicity. Beside the fact that Lin was the 12th man on a 12-man team, that he was undrafted out of Harvard, a school that produces CEOs and politicians, not pro basketball players; beside the fact that he was with his third NBA team in two seasons and got meaningful playing time only in a developmental league, he's also an Asian American. And if this is the story that keeps on giving, one of the things it gives some of us is a headache because we're not real comfortable talking about race.

The liberal view on Jeremy Lin is that his heritage should not be part of the fascination, for fear of cheating the noteworthiness of his accomplishment. But how in the world can we ignore it? Let's be honest, Lin's being an Asian American is part of what makes this story unique. A few Asians have made the NBA, but Yao Ming and Yi Jianlian were accomplished players imported from Asia, not point guards from Palo Alto, Calif., who may have been disregarded as basketball prospects from the jump because of race.

It is rare and it is also wonderful. Folks of Asian heritage around the world have rejoiced. People in Taiwan, where Lin's parents lived before emigrating to the United States in the 1970s, have plugged in their satellite dishes and sit huddled around the television to watch Knicks games. It's called ethnic and nationalist pride, along the same lines as African Americans worshipping Jackie Robinson or Italian Americans doing the same with Joe DiMaggio. Not even a misguided misanthrope like boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr. can rain on this parade.

Maybe Mayweather was trying to drum up attention for another one of his meaningless fights that again won't include Manny Pacquiao, or maybe he was just being plain ignorant when he tweeted that "black players do what [Lin] does every night and don't get the same praise."

When Kobe Bryant goes on a scoring tear with a streak of 40-plus-point games, does he not get headlines? If a 5-foot-3 black player such as Muggsy Bogues were still in the league and rained down the same numbers as Lin, does Mayweather think he wouldn't get the same acclaim? Come on, Floyd, let's be real. Unique is a story, and in Jeremy Lin's case, his Asian American pedigree is an honorable part of this, just as Bogues' lack of size would be.

And now the Lin story shifts to another gear, as we discuss how symbols honor or insult him. The latest outrage comes from a sign held up by a fan shown prominently on New York cable network MSG. On the sign, Lin's head pops out of a fortune cookie. Underneath it reads, "The Knicks good fortune."

Through time, we have seen clearly how food references can be interpreted as ethnic slurs. More conversation will enable us to come to grips with this fortune-cookie thing. But I have to laugh when I hear folks say that we're being too politically correct by considering whether a fortune cookie sign can be racist. How is it possible to become too politically correct, and who are we to tell other cultures whether or not they should be offended?

In the meantime, we relish Jeremy Lin.

You'd have to go back to Kurt Warner, Fernando Valenzuela, or Mark Fidrych to find similar stories. Warner was a grocery bagger before he became an NFL star. Valenzuela was a chubby mystery man from Mexico before he birthed Fernandomania. And Fidrych was a Big Bird-like car mechanic from New England who talked to the baseball and dazzled the American League in 1976.

But I also think of Ruben Amaro Jr.

Amaro had a Jeremy Lin moment in 1992. In the lineup as the Phils starting centerfielder after Lenny Dykstra got hit by a pitch and broke his hand on opening day, Amaro caught fire. He had three hits, two doubles, and three RBIs in his second start. Through his first seven games, Amaro hit .304. His start was so auspicious, Phils fans started clamoring for the team to trade the exasperating Dykstra, who had been banged up in a car accident and broken his collarbone while driving drunk the year before. But by the end of April, Amaro's batting average faded to .138 and his playing career here evaporated.

Keep your head up, Jeremy. Even if you never make another shot, you might have a burgeoning career as a general manager.