Stan Hochman: Remembering the terrorist attack at the 1972 Olympics in Munich

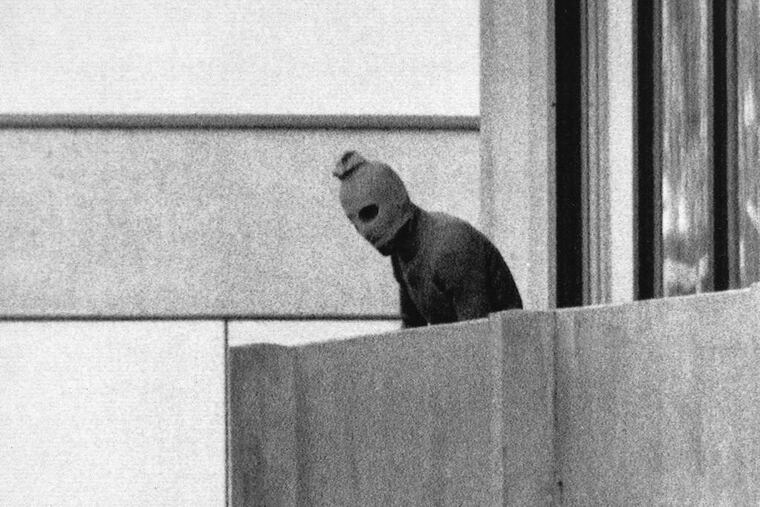

The killer in the ski-mask, that assassin with the machine gun cradled in his left arm ... that terrorist on the balcony of the dormitory that housed the Israeli athletes and coaches ... that madman barking demands to the wide-eyed woman in the pastel jacket, armed only with a walkie-talkie ... I stood 40 yards away, on a hillside, peering through a chain-link fence, watching the 1972 Munich Olympics crumble into tragedy.

The killer in the ski-mask, that assassin with the machine gun cradled in his left arm ... that terrorist on the balcony of the dormitory that housed the Israeli athletes and coaches ... that madman barking demands to the wide-eyed woman in the pastel jacket, armed only with a walkie-talkie ...

I stood 40 yards away, on a hillside, peering through a chain-link fence, watching the 1972 Munich Olympics crumble into tragedy.

The fence wasn't even child-proof. In an effort to represent joy and youth and carefree spirits and human dimensions, the Olympic security people wore sky-blue and peach-colored uniforms. They carried no weapons.

And the terrorists slithered over that short fence late at night and shot Moshe Weinberg in cold blood inside Apartment 1 at Connollystrasse 31. They stormed inside, held the others hostage, and then murdered them at the airport when the flimsy German plans for an ambush fell apart.

It is 40 years later and the International Olympic Committee has rejected proposals by the Israeli government to hold a moment of silence at the London Games in memory of the 11 Israeli athletes and coaches murdered by those Palestinian killers at Munich.

The IOC said "No!" And then offered this bit of mumbo-jumbo: "What happened in Munich in 1972 strengthened the determination of the Olympic Movement to contribute more than ever to building a peaceful and better world by educating young people through sport practiced without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit."

The '72 games resumed after 24 hours. The tyrant who ran the games, Avery Brundage, babbled about how the games must go on. Same guy who helped put the 1936 games in Berlin, in Nazi Germany. The games resumed before they'd scrubbed Moshe Weinberg's blood from Building 31.

The fighters fought and the divers dove and the swimmers swam and Mark Spitz paused before fleeing the Olympic Village to mumble that he "didn't want to become a lamp shade." In the pages of the Daily News, I scorched him for his stupidity and found an avalanche of hostile mail when I got home.

The games had shifted from higher, stronger, faster to uglier, bloodier, deadlier. The games resumed and I wrote about them. But first I attended the solemn services for the slaughtered Israelis. The Russians did not.

I watched Teofilo Stevenson thump Duane Bobick in the quarterfinals of the heavyweight boxing tournament. And I watched Doug Collins get hammered and stagger woozily to the foul line and make both free throws in the gold-medal basketball game. The U.S. team was on its way to beating the Russians when they got mugged and robbed.

I typed the protest, dictated by a couple of angry, bitter U.S. basketball officials. It was a German typewriter and there was a 'Z' where the 'Y' ought to be.

I remember linking up with the Bulletin's Jim Barniak and talking our way into the Olympic Village the day after the game, discovering that the U.S. players would refuse to accept their silver medals. Barniak died in 1991 at age 50 ... much too young. Stevenson was 60 when he died last month in Cuba. Collins coaches the Sixers, and I wonder how often he thinks of those tragic Olympic games.

I remember interviewing Olga Fikotova Connolly, the Czech discus thrower who had married U.S. hammer thrower Harold Connolly. She competed for the U.S. in Munich and was chosen to carry the flag in the Opening Ceremony. There had been some rancorous debate about that because she had spoken out against U.S. military involvement in Vietnam.

"I will go to practice today," she told me. "And I will go and compete. And momentarily I will enjoy myself competing. But it will still be burning inside me, what a terrible tragedy this was. Things have to be done. I have to be part of the change.

"Maybe this will open people's eyes? Maybe something positive can come out of this tragedy? I don't want those people to have died in vain."

The IOC spurned the request for a minute of silence this year. Too political. As if somehow the games go on in a bubble, without uniforms and flags and anthems and ancient vendettas.

I was there in 1968 in Mexico City for the black-gloves moment on the victory stand, for Tommie Smith and John Carlos and their eloquent pantomime on behalf of truth and justice. They were exiled from the Olympic Village the next day.

I was not there in 1980 in Moscow, because no U.S. athletes were there, our government's protest against the Russian tanks rumbling into Afghanistan at the time. I covered Montreal in '76 and Los Angeles in '84 and that was enough. Access to the athletes was tougher, joy was harder to find.

I wonder whatever became of Olga Connolly, and if, at 79, she is still fighting the good fight, and if the scar on her heart has healed. And I wonder if 40 years later we are any closer to world peace and justice for all.

I will hit the mute button for a minute when the London Games begin and I will try not to think about that killer in the ski-mask, cradling that machine gun he had smuggled into the Olympic Village, slithering over that puny fence.