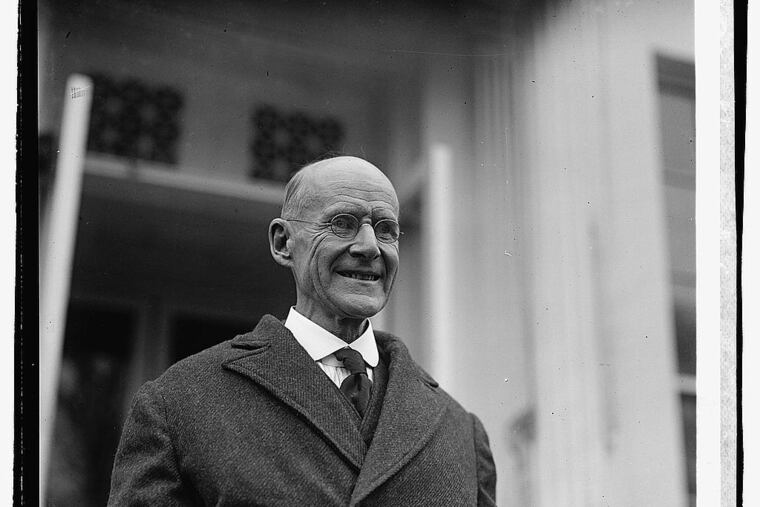

A presidential candidate has run from prison in the past. In 1920, this socialist won nearly a million votes.

Eugene Debs was a force in American politics in the early 20th century.

This article was originally published by the Washington Post on Sept. 22, 2019.

Eugene Debs did not speak on election night in 1920. The Socialist presidential contender was, in his words, a “candidate in seclusion,” imprisoned in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary for speaking out against the draft during World War I.

Outside the lockup, his supporters handed out photos of Debs in convict denim along with campaign buttons for “Prisoner 9653.” Reporters had hoped to hear a fiery oration. But the warden did let Debs write out a statement.

“I thank the capitalist masters for putting me here,” he wrote. “They know where I belong under their criminal and corrupting system. It is the only compliment they could pay me.”

Debs railed against capitalism a century before Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., would campaign for the White House as a democratic socialist. And before President Donald Trump would seize on the word “socialism” to denounce his opponents, declaring that “a vote for any Democrat in 2020 is a vote for the rise of radical socialism and the destruction of the American dream.”

In 1920, Debs was the ultimate radical. He’d run for president on the Socialist Party ticket five times since 1900. Eight years earlier, he’d won 901,551 votes — about six percent of the vote. However, this time he was politicking from behind bars.

He’d opposed U.S. involvement in World War I, believing the war only benefited arms manufacturers and business interests. In July 1918, while speaking in a Canton, Ohio, city park, he denounced the “Junkers of Wall Street” and criticized the government for arresting antiwar activists.

“They have always taught and trained you to believe it to be your patriotic duty to go to war and to have yourselves slaughtered at their command,” Debs said. “But in all the history of the world you, the people, have never had a voice in declaring war, and strange as it certainly appears, no war by any nation in any age has ever been declared by the people.”

He added emphatically: “The working class who freely shed their blood and furnish the corpses, have never yet had a voice in either declaring war or making peace. It is the ruling class that invariably does both. They alone declare war and they alone make peace.”

Under the Sedition Act of 1918, such words were treasonous. The act, an amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917, sought to silence those who spoke out about the war.

Federal prosecutor Edwin Wertz, who had sent a stenographer to the park, announced he would indict Debs.

“No man,” Wertz said, “even though four times the candidate of his party for the highest office in the land, can violate the basic law of this land.”

Many Americans opposed U.S. involvement in the Great War — and they did more than protest. In Indiana, an entire county’s draft cards were stolen. In Minnesota, banks that supported the war effort were boycotted. Throughout the nation, draftees skipped physicals, gave a wrong address at their induction or filed claims for exempted status.

A backlash soon followed. The Postmaster General banned delivery of left-wing publications such as The Nation, Mother Earth and The Masses. The American Protective League, a quasi-vigilante group, joined the police on “slacker raids,” random dragnets where draft-aged men were required to produce their draft cards — sometimes at the point of a bayonet.

In the Supreme Court case “Schenck v. United States,” socialists were accused of urging resistance to the draft among those eligible to serve. In a unanimous opinion upholding the case, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes argued “the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.”

Debs’ trial for sedition was a mess. In testimony, it became clear that Wertz’s stenographer — a car salesman — had failed to transcribe most of the speech. Wertz called several draft-age men in a vain attempt to prove the speech discouraged registration. However, each one had registered, and one was even in uniform.

The defense called only one witness to the stand: Debs, who promptly admitted his guilt. Ignoring objections from prosecutors, the judge then allowed him to address the court for nearly two hours.

“What you may choose to do to me will be of small consequence after all,” Debs said, concluding his remarks. “I am not on trial here. There is an infinitely greater issue that is being tried in this court today. American institutions are on trial before a court of American citizens. Time will tell.”

The jury found him guilty. On Nov. 18, 1918 — a week after Armistice Day — he was sentenced to three concurrent 10-year sentences and lost his right to vote. Though he appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. found a clear intention to obstruct the draft.

Through his rabble-rousing orations, Debs had been the public — and charismatic — face of socialism. He founded the Socialist Party of America in 1901, but its roots went back to his work as a union organizer in the rail yards.

In the 16 years before the U.S. entered World War I, the Socialists elected congressmen in New York City and Milwaukee and put 40 mayors into city halls around the country. In April 1917, only days after the U.S. entered the war, the party ratified an antiwar platform.

Though he ran for president five times, Debs was a reluctant leader. And he knew his campaigns were symbolic.

“There was virtually no chance that a Socialist (or any third-party candidate) would ever get the votes needed to break through the electoral college, so at best the party’s national ticket for president and vice president was always a way to raise awareness and encourage further organizing of working class people,” said Wesley Bishop, a historian at the Eugene V. Debs Foundation.

Suffering from a heart condition and believing the party needed new faces, Debs had sat out the 1916 presidential election. Now, as so many dissidents — anarchists, socialists, suffragists, pacifists, even conscientious objectors — had been ensnared by the Sedition Act, he felt compelled to campaign again from behind bars.

This was not his first prison sentence. A much younger Debs, then president of the American Railroad Union, had served time for involvement in a national railroad strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company. Owner George Pullman had refused to reduce rents for laid-off employees in his company town. Because the Pullman cars carried U.S. mail, President Grover Cleveland sent the U.S. Army in to quell the conflict.

By the strike’s end, 30 were dead and nearly $80 million worth of property had been destroyed. As union president, Debs received a six-month sentence. He said he became a socialist after reading Karl Marx’ “Das Kapital” while in prison.

Despite this Debs, “was not a close reader of European socialist doctrine,” said Ernest Freeberg, author of “Democracy’s Prisoner: Eugene V. Debs, The Great War, and The Right To Dissent.”

“He liked to quote Thomas Paine. He was a great admirer of the abolitionists like John Brown and Wendell Phillips,” Freeberg said. “(To Debs) the American Revolution was the first step for democracy, the overthrow of slave holders was a further step, and the Socialist fight against the ‘wage slavery’ of capitalism was the next great challenge. He captivated audiences because he presented socialism in an American grain.”

In the 1920 election, Debs and his running mate Emil Seidel garnered 913,693 votes, but — as in his previous campaigns — no electoral votes. The winning candidate, Democrat Warren Harding, promised a “return to normalcy,” restoring the prewar way of life.

On April 13, 1920, the Socialists demonstrated in front of the White House and delivered a petition for Debs’ pardon. Film star Mae West wrote to Harding to push for a pardon.

Almost a year later in March, the warden drove Debs to the rail station. He then boarded a train for a trip to Washington — unaccompanied and unsupervised — to meet with Attorney General Harry Daugherty at Harding’s behest.

The White House planned to keep the meeting secret, but Daugherty, a blustery, machine politician, bragged about it to reporters. When the news hit the papers, veterans groups protested and Harding now had to factor in the political optics of their opposition. He finally released Debs on Dec. 21, 1921 — just in time for Christmas.

“He is an old man, not strong physically,” said Harding when commuting the sentence to time served. “He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”

En route to his home in Terre Haute, Indiana, a gaunt and weary Debs stopped at the White House for a meeting with Harding. There is no record of what either man said. Debs died in a suburban Chicago sanitarium, while being treated for his heart condition, in 1926.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter pardoned many Vietnam War draft resisters who had fled to Canada. But Eugene Debs, imprisoned for his opposition to an earlier draft, has never been pardoned.