Broad Street Ministry is making sure people can vote by mail — even if they have no address

“Even though people may be poor, they still know what’s going on in the world.”

When she got to the spot on the voter-registration form that asked for her Social Security number, Yvonne Stratton shook her head emphatically.

“I’m not putting my Social on there!” said Stratton, 58, lamenting a recent battle with identity theft. “I guess I’m not voting!”

Then, Brian Hughes approached. In calm tones, the voter-registration worker for Broad Street Ministry assured her that her state ID number would suffice. Stratton, who normally doesn’t vote, said she’d go ahead and give it a try‚ even though she’s been disgusted by the campaigns’ political mud-slinging. (“I thought only street people did stuff like that,” she said.)

Stratton can’t say much for the candidates. “All I can say is, Broad Street Ministry has been there for me for 15 years. They helped me out more than my own family.”

The organization, which doubles as the mailing address for 3,000 people who are homeless or housing insecure, this year faces a monumental logistical and civic challenge in ensuring that all of those visitors have a voice in the election. The introduction of mail-in voting has made that prospect more complicated than ever, since thousands of applications and ballots could be filtering through the bustling mail room.

So, Broad Street is running a pilot civic engagement project, aiming to ensure each guest has the opportunity to make their vote count.

Every step of the process requires attention and care, said LeBrian Brown, Broad Street’s reentry and civic-engagement coordinator.

For one thing, people have to feel comfortable: “A lot of them have told me that they haven’t registered because they weren’t comfortable with how people approached them: They just come up to them on the street, and ask them for their registration, and leave," he said.

For another, when life is chaotic, voting can feel like a monumental endeavor. Clients tell him they may not remember to vote. Or, they’re open to voting by mail — but might forget to put their ballot in the mailbox.

» READ MORE: Everything you need to know about voting by mail, or in person, in Pennsylvania

With a $25,000 grant from the Independence Foundation, Brown hired voter-registration temps to staff the nonprofit five days a week during the daily lunchtime crush, when 300 or more visitors crowd in to grab meals, pick up mail, or inquire about other services. He looked for workers he thought visitors could relate to, like Hughes, who is also a regular guest at Broad Street.

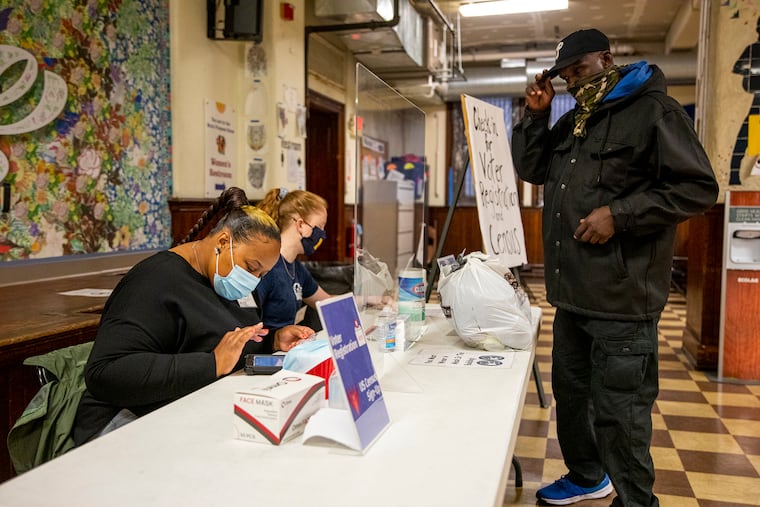

One worker staffs a voter information table near the mail hub, ushering those who want to register upstairs to the peaceful, stained-glass-lit sanctuary, where Hughes and another temp, Zhane DeShields, walk them through the registration form.

It’s a time-intensive process: People start with many questions and misconceptions. They think they’re not eligible to vote because of past convictions. Or, they think voter registration is voting, not the first step in a process.

» READ MORE: Pennsylvania now lets everyone vote by mail. But poor people in Philadelphia haven’t benefited.

“You have to have patience with people,” Hughes said. “It’s being able to sit with them and give them some time. Let them talk about their day. A lot of people we’re dealing with have mental illness, so just to sit down and talk to them about anything makes them feel comfortable.”

He asks clients questions unlike anything you’d expect to hear at a voter registration drive. Things like: "If you could go back to any age, what age would you go back to?”

Lang Blanding, 60, with a halo of gray hair and shopping bags clustered at his ankles, knew the answer right away: He’d be 8 again. He’d do it all over, this time with focus. “White folks, if a kid says I want to be a baseball player or a ballet person, they push the issue," he said. "They didn’t push the issue with me.”

Blanding, who’s staying at a shelter in West Philadelphia, was not sure where he was registered, or even whether in-person voting was taking place this year.

“I used to always think that my vote didn’t count,” Blanding said. But maybe this year his vote would be a tie-breaker.

He doesn’t mind traveling back to Center City to get his mail-in ballot application.

“Coming here is like the highlight of my day,” he said.

So far, there are 1,444 people registered to vote at Broad Street Ministry.

St. John’s Hospice, which receives mail for about a thousand people, counts only 260 registered voters. (Administrators did not respond to a request for information about voter registration efforts there.)

At the Kensington nonprofit Prevention Point, where more than 4,000 people get mail, about 400 voters are registered.

Its executive director, Jose Benitez, said mail usage has nearly tripled in the last two years, so just keeping up has strained their resources. But, he said, voter registration is available year-round at Prevention Point.

“If they come in for medical services, we ask, ‘Are you registered to vote and if not would you like to?’ If they come in for mail, we ask, ‘Are you registered? Would you like to register?’ If they come in for a meal, we do the same thing. No matter what service you receive here, we’re asking."

» READ MORE: What to do if you haven’t received your mail ballot yet in Pennsylvania

At Broad Street, after voter registration closed on Monday, the civic engagement team was shifting to helping people who want to request mail-in ballots.

DeShields expected demand would be high: “Most of them really want a mail-in ballot. That’s the first thing they ask.”

The next puzzle will be how to ensure those mail-in ballots are cast and counted. Brown hopes to set up an on-site mail drop, though logistical hurdles remain.

One thing Hughes has learned is, people do want to be heard.

“Even though people may be poor," Hughes said, "they still know what’s going on in the world.”