Philadelphians have questions about the removal of slavery exhibits. Independence Park employees are being told to give evasive answers

Talking points include telling visitors that exhibits at the President's House were removed "to ensure compliance with the Secretary's Order," according to internal park correspondence.

Visitors at Independence National Historical Park strolled through what was left of the President’s House Friday afternoon, some stopping to inspect the blank brick and streaks of glue residue where exhibits about slavery were displayed for 16 years.

That is, until the National Park Service dismantled them a day prior.

At about 12:30 p.m. Friday, a group of teachers spent their 45-minute lunch break taping up colorful signs across the bare walls as a small act of resistance: “Learn all history,” and “History is real,” the posters read.

But if any of Friday’s visitors had questions about why the slavery exhibits at the President’s House were removed, they’d be hard-pressed to receive an exact answer from park employees.

Soon after Thursday’s dismantling of the President’s House — which memorializes the nine people George Washington once enslaved there — employees were reminded by the Park Service to use “talking points” that essentially evade visitors’ questions, according to internal correspondence reviewed by The Inquirer.

The message suggests the following lines to park employees, while also instructing them to answer “truthfully”:

“[I am not aware of] why this [exhibit/interpretation materials] has been [changed/removed]”

“[Exhibit/interpretation material] has been [updated/removed] to ensure compliance with the Secretary’s Order.”

“If visitor continues to ask questions that you are unable to answer, politely refer them to AskNPS@nps.gov,” the message further outlined.

This messaging comes amid the confusion and anger surrounding President Donald Trump’s administration’s efforts to review or potentially remove content at national parks that “inappropriately disparage Americans past or living,” according to orders from Trump and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum.

“It’s outrageous what they’re doing,” said Kaity Berlin, a social studies teacher who was among the group at the park Friday.

“At the smallest level it’s a waste of resources; at the biggest level, [it’s an] erasure of history,” added Berlin, who declined to say where she worked.

The President’s House received intense scrutiny from Trump and Burgum’s orders, culminating in the total dismantling of all displays at the site Thursday — even those that were not originally flagged by park staff for review last year.

It’s not just the public that has questions. Local lawmakers want answers, too.

On Friday, Democratic U.S. Reps. Brendan Boyle, Dwight Evans, and Mary Gay Scanlon, who all represent parts of Philadelphia, penned a letter to Burgum and Park Service Acting Director Jessica Bowron demanding answers to specific questions about the removal by Jan. 30. They also said they believe the dismantling violates an existing agreement between the Park Service and the city.

“Trying to remove that history just because it makes some people uncomfortable is deeply troubling. When a government starts hiding parts of its past, it begins to look more like a regime that rewrites history rather than one that learns from it,” the lawmakers wrote.

The lawmakers want to know why the exhibits were taken down and who authorized the decision, according to the letter.

The letter also asks for information on what role senior Trump administration officials played, where are displays being stored and if there’s plans for them to be reinstalled, and what other documents or items exist related to the removal of the exhibits.

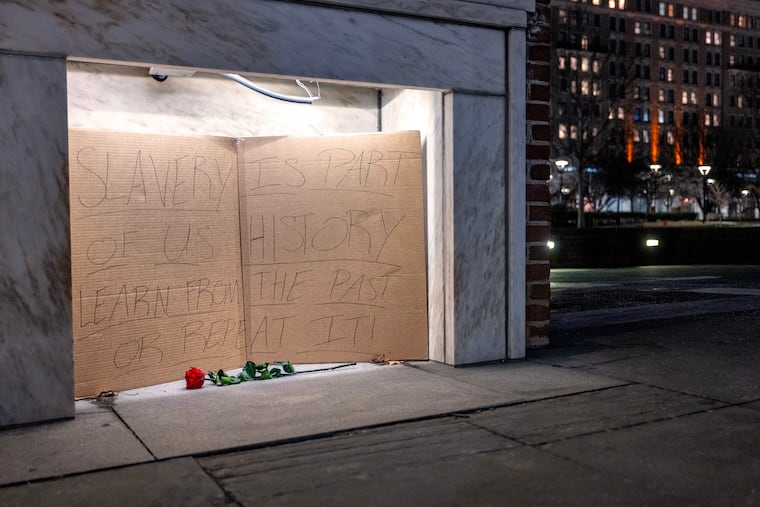

At the President’s House Friday afternoon, it appeared that many Philadelphians were adamant about preserving this history.

A bouquet of flowers was placed at the feet of the marble wall inscribed with the names of nine people enslaved there by Washington. A single red rose rested inside one of the site’s fireplaces; a sign, “Slavery was here, Philly hates fascists,” rested against a wall.

“Everybody has been fighting for so long to teach all pieces of history, not just one side of it,” Berlin, the teacher, said.